Bryson & McDill Political Map - Statism vs Anarchy, Right vs Left

We recommend that along with this section of the Culture War Encyclopedia, you see the political alignment charts section.

In “The Political Spectrum: A Bi-Dimensional Approach”, published in the

Rampart Journal of Individualist Thought, Vol. IV', No. 2, Summer, 1968, authors Maurice C. Bryson and William R. McDill write,

Laurence McGann in "The Political Spectrum" (Rampart Journal, Winter, 1967) raises some cogent arguments concerning the form of a proper model for the political spectrum. Briefly, the following points may be noted. First, a simple linear picture of a left-to-right alignment, with communism at the far left and fascism or nazism at the far right, is unsatisfactory in that it neglects the essential similarity between these two extremes, viz., their common totalitarianism. This similarity gives rise to a circular model in which communism and nazism occupy adjacent locations, with "democracy" at an intermediate location on the other side of the circle. Mr. McGann quite properly criticizes the circular model for ignoring the possibility of political structures that are more free, or less totalitarian, than existing democratic ones.

We regret that we were unable to find a copy of this issue of the Rampart Journal or Laurence McGann’s "The Political Spectrum". Bryson and McDill continue,

He then proposes an alternative linear model in which the linear position represents not "Ieft-" or "right-ness," but rather degree of government control, with degree of individual safety as a concomitant variable.

Another criticism, more severe from an analytical viewpoint, could have been leveled against the linear and circular models. This consists of a failure to recognize important distinctions between alternative philosophies which tend to be lumped together or at least closely associated in any linear model. Specifically, the term rightwing is commonly used to denote not only fascism, but also such concepts as the objectivist philosophy of Ayn Rand or the laissez-faire economics of Milton Friedman. And yet, even the most biased of analysts must recognize profound differences between these latter philosophies and fascism; since, in fact, these differences would appear to place the conflicting viewpoints practically at opposite poles:, it is obvious that no small modifications in the form of the political spectrum can account for the differences. Moreover, substantially similar criticisms could be leveled against the linear model proposed by Mr. McGann. In classifying ideologies only according to the degree of governmental control, his structure lumps together fascism and communism at one extreme-a grouping which might not appear totally unreasonable in today's political environment, but one which would have been badly misleading before the Second World War. More dangerously, it lumps together at the other extreme those whose philosophy is dominated by an opposition to governmental control, whether they be Goldwater Republicans or "hippies" opposing narcotics regulations. Once again, the differences between the groups are too important to be glossed over.

Many of these problems may be resolved by recognizing that we are in fact confusing two political issues that are quite distinct: the degree of government control that is exercised, and the direction in which that control is applied. Control, regardless of its magnitude, may be used to promote egalitarianism within society (the classical "left-wing" goal), or may be used to promote stability within society and hence allow the more qualified to maintain social advantage. To be sure, at the extreme points some of .these distinctions may be moot points: in a state of total anarchy, there is no governmental control and hence the question of how control is being applied becomes indeterminate; and if governmental control is absolute, then all citizens are subordinate to the state and the question of egalitarianism vs. privilege becomes meaningless. But these are pathological cases of little interest in a functioning society. At all intermediate points, the difference between the two issues is of great importance.

We therefore arrive at a bi-dimensional model of the political spectrum. Position on the vertical axis represents the degree of governmental control advocated (statism vs. anarchy), and position on the horizontal axis represents the degree of egalitarianism favored (left V8. right). To clarify the picture, labels in the four quadrants identify some of the traditional philosophies of governmental structures that might be located there:

The center, or origin of the coordinate system, is clearly arbitrary; it is intended to represent in a general sort of way the political center of gravity of the population being considered. As such, its location can of course vary according to the temper of the times.

The concept of political dimensionality is not completely new (for some interesting comments, see for example H. J. Eysenck's Sense and Nonsense in Psychology [Pelican Books, 1957, ch. 7).

In Eysenck’s Sense and Nonsense in Psychology the model of political dimensionality he uses is the same model he uses in 1954 book The Psychology of Politics, the model we looked at above. In fact, he uses the very same illustrations we saw above as Figure 16 A, Figure 16 B and Figure 16 C. Let’s refresh our memory, however.

Image above from Sense and Nonsense in Psychology, by Hans Eysenck, chapter 7, page 281.

Bryson and McDill continue,

However, its ramifications have evidently yet to be explored in depth. Most important for our current purposes, it explains some of the paradoxes that were noted in connection with linear or circular models.

Consider for purposes of idealization an observer whose own philosophy locates him precisely at the center of gravity, or origin 0 of the system. If he considers the relative positions of a conservative Republican at position R and a liberal Democrat at position D, they will appear to him to be totally at odds in their philosophies; they might even seem to represent the two political extremes on a small or local scale. But now, suppose he views a fascist at position F and a communist at position C. In reality these two are more widely separated in their philosophies than are the local Democrat and Republican; but when our observer at 0 looks at them, they do not appear to be at all in opposite directions. On the contrary, as indicated by the arrows, they are in roughly the same direction as far as the observer is concerned. Their common totalitarianism appears, to him, to outweigh completely whatever differences in method they might have.

Yes, in fact, it is no trouble for we here at the Culture War Encyclopedia to note that communism and fascism (and also Nazism) are forms of totalitarianism. Stalin, Hitler and Mousseline were all dictators. Hence, we made the following. In our experience, some people do have trouble seeing it. These people tend to have the hammer and sickle in their social media bio. They see themselves as being opposite of Nazism and fascism. If I could find anyone who actually supports actual Nazism and/or fascism, I would bet that they too would claim that they are the polar opposite of a communist.

Is it not true that the terms fascist and Nazi are often used interchangeably? What about communism or socialism or Marxism or whatever term you prefer? Why is that not used interchangeably with fascism or Nazism? Is it some sort of institutional bias?

Returning to Bryson and McDill, they continue,

A person with more statist leanings, however, would be more likely to discern the differences; and an individualist who locates himself near the anarchist extreme might even say that C, F, D, R, and 0 all look like a pack of totalitarian scoundrels with no important differences at all. Thus we have the natural submersion of differences that leads to such confusions as the circular-spectrum model.

The questions of "individual safety" posed by Mr. McGann also fit nicely into the bi-dimensional framework. He argues that the individualist must be willing to accept a certain amount of governmental control in order to maximize his personal "safety-freedom"-that is, to achieve a satisfactory balance between safety from the arbitrary encroachments of his neighbors and freedom from the arbitrary whims of the state. For the individualist whose ideal society would simply permit him to develop his own talents to the utmost, the safety factor is inherent in the left-right axis. In general, the farther right the existing political climate, the more protection the individual will have from others in society. However, it should be clear that as a political structure takes on a more right-wing aspect, it must also accept a greater degree of governmental control to remain stable. An extremely competent individualist! might ideally like to see a governmental system in the far lower-right-hand corner of our coordinate plane, with virtually no government interference, but with the minimal government control being used to permit the widest possible spectrum of individual rewards. Obviously, such a system would not long endure; in the absence of governmental restraint, the disprivileged masses would sooner or later rise up to demand a degree of egalitarian reform. We may generalize to the extent of noting that the farther an individual locates himself to the right, the higher the position on the statist axis he will be forced to accept in order to realize any viable over-all position. The individual's location of his philosophy on the left-right axis corresponds to his generation of safety-freedom preference curves in Mr. McGann's terminology. Considerations of feasibility then determine how far he must go up the statist axis; this corresponds to the location of a safety freedom maximum as described by Mr. McGann.

The authors have found the hi-dimensional spectrum to he an especially useful tool in discussing and analyzing the mechanics of political activity-a somewhat more complicated process than the descriptive one of identifying an ideology. The mechanics of a political process seem to be most affected by two readily understood phenomena. First, while the most qualified, well-educated, and influential persons in society tend to be located to the right of center, the great mass of voters tends to be slightly to the left. This merely reflects the well-known Lincoln aphorism about God's apparent love for the common man; but more important for our purposes, it means that a political party or coalition cannot long remain in power if it is totally denied access to the masses of left-of-center voters. The second phenomenon, equally understandable, is that the party in power inevitably moves toward a more statist position. That is, it seems much more likely that one will attempt to justify the application of political power if one has the power. Once the power is applied, of course, there tends to be a coalescing of opposition in the opposite quadrant. How well and how fast the opposition may extend its influence seems to depend on many facets of the then-existing political environment.

Hence, the political process as pictured on the coordinate graph takes on the appearance of a stylized little clockwise minuet. The party-in-power moves toward a statist posture. The opposition appears somewhere in the anarchist half-plane. Required by the exigencies of running the government, the "ins" begin to draw on the well-qualified citizens of the upper-right-hand quadrant, thus drifting toward the right. As soon as the "outs" recognize the opportunity and can cast off the necessary ideological encumbrances, they can effect a coalition with disaffected citizens in the lower-left-hand quadrant; the "ins" are always vulnerable to attack at the right flank. (The simile is structural, not political; the right flank, in political terminology, is really the left wing.) Finally, since most of the voters are left of center, the "outs" have the opportunity of getting a majority, whereupon they become "ins" and the process begins again.

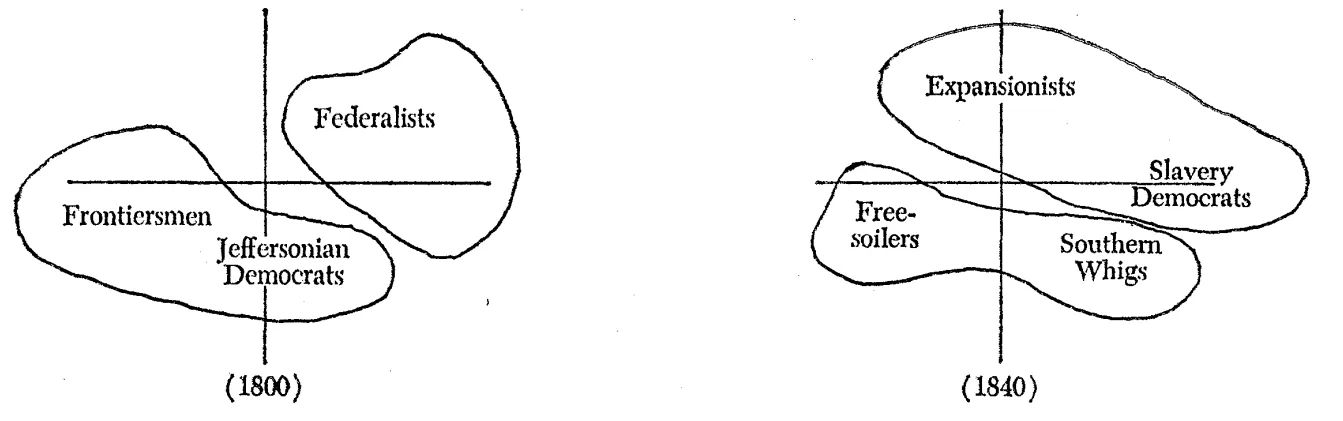

This process may be seen in the accompanying series of diagrams, giving a simplified picture of how a history of American political developments appears graphically. First, after the initial Federalist.

governments before 1800, the Jeffersonian Democrats allied themselves with the frontiersmen in the new Western states to form the first real political party. From this coalition came the Jacksonian Democratic party and its left-wing-based opposition to the National Bank in the 1830's. Growth of the government's power led to the Whig reaction against ':'King Andrew" after 1830.

To the extent that the Whigs were able to ally themselves with free-soilers in the West, they were able to realize political success in the 1840's. But the alliance was too tenuous to withstand such an emotional issue as slavery, and the party eventually fell apart resulting in the growth of the new Republican party, based in the politically prosperous domain of the old free-soilers.

Under the impact of the Civil War, the Republican party was not long in becoming statist. By 1870, it was a powerful but politically vulnerable alliance of "bloody-shirt" reconstructionists and businessmen of the prosperous Northeast. To the opposition went the partially disenfranchised South and the still-weak labor and grange organizations. The Democrats ~were organizationally very weak during the closing years of the nineteenth century, but were tapping enough of the lode of left-of-center votes to be a constant threat from 1876 on.

By 1900, the Democrats had reached substantially a position of parity, although the individual popularity of its candidates and the generally high level of prosperity in the country kept the Republicans in power. But by the 1920's, the Democrats had forged an alliance of potentially mammoth proportions, including Southerners, most farmers, urban minority groups, and labor. With the obvious strength of this coalition, the magnitude of Democrat victories after 1930 is not at all surprising.

Since 1930, the Republican party has been a basically weak alliance of business and the rural right wing-isolationist at first, then anti-communist-interventionist. By 1948 and 1952, however, the vulnerable right flank of the statist coalition finally started falling apart; first the Southerners fell out, and more recently the anarchistic "new left" has evidenced the continuing disintegration. Once again, the "ins" today are vulnerable to attack within the political heartland, where the votes are.

Whether the Republicans can soon effect enough. of a coalition to get a winning combination is problematical. Only with great difficulty has a Republican-Southern bloc become a factor in presidential elections, and the current prospects of getting many votes from farther to the left. are remote indeed for the Republicans. Party of the problem is the essential truth that there are not many political entities active in the lower half-plane of the spectrum, ("organized anarchists" being somewhat of a contradiction in terms). Thus, there is little communication among the disaffected groups. Nevertheless, the opportunity for coalition is there. The Goldwaterites who oppose public welfare programs and the Berkeley radicals who oppose public police measures have much more in common than either would care to admit. Moreover, there are other signs of incipient coalitions forming, notably, the inroads among white minority groups made by the George Wallace forces. Finally, some of the liberal "ins" themselves have taken note of the threat. In his commentary following the 1968 State of the Union address, Daniel P. Moynihan made the highly cogent observation that the political strength of the future belongs to that group which can best capitalize on the groundswell of anti-government, anti-establishment opinion, both left and right, among the young.

The foregoing has concentrated on the relevance of bi-dimensionality to domestic politics. Internationally, the picture gets more complicated, but many of the same concepts are relevant. For example, the establishment of Mao Tse-tung:>s totalitarian-but-classless society in China provides a textbook example of extreme left-wing statism, vividly demonstrable in the graphical system even though far outside the domain of typical American political activity. Meanwhile in the Soviet Union, one can see the natural drift of such a left-wing statist society toward the right, in search of managerial talent.

Finally, it should be noted that while the two axes used in the discussion here appear to be the most useful ones in general, they are not exhaustive. Under some circumstances, issues which cannot be categorized as left-right or statist-anarchist, and which are in fact independent of these axes, can become important. A clerical-anticlerical axis has always been relevant to French politics, and was vitally important to the United States in 1928. Under wartime conditions, an internationalist-isolationist axis may supersede the others (although pro-war groups are sometimes identifiable uniquely as right-wing statists). A white-black "racism scale” and an active-passive "degree of radicalism scale” could also be considered, and in the future the advent of sensitive scientific questions could introduce altogether new issues. In any event, though, it seems to the authors that much is to be gained from the principle of bi-dimensionality or multi-dimensionality in political discourse-both philosophically and practically.

Again, we recommend that along with this section of the Culture War Encyclopedia, you see the political alignment charts section.

Others claim & move on, we prove & archive forever.

∴ Liberty ∴ Strength ∴ Honor ∴ Justice ∴ Truth ∴ Love ∴ Laughter ∴

Culture War Encyclopedia on