L.F.E. Theory of the Political Spectrum

We recommend that along with this section of the Culture War Encyclopedia, you see the political alignment charts section.

In “The L.F.E. Theory Of the Political Spectrum” published in the Rampart Journal of Individualist Thought, Vol. IV', No. 2, Summer, 1968, pages 27-31, Bowman N. Hall writes,

A graduate of Wabash College (A.B., 1966), Bowman N. Hall, II, is a candidate for a Ph.D. in economics at Duke University. He is presently a part-time instructor of economics at St. Andrews College in Laurinburg, North Carolina.

The thoughts expressed herein were sparked by Laurence McGann's "The Political Spectrum" which appeared in the Winter, 1967, number of this journal.

There is a footnote at this point in the text that reads,

Readers might be well advised to review this article to gain a better perspective on the L.F.E. theory.

Returning to the main text,

Mr. McGann there rightly criticized the circular theory of the political spectrum (Figure 1) for it includes no political situation less collectivized than democracy. Thus it fails to meet the requirement that any such theory must include all possible forms of political condition. Anarchy, the state of no political regimentation, does not appear on the circular theory.

Realizing that the circular theory is unacceptable, Mr. McGann suggests the linear theory of the political spectrum (Figure 2) as a more valid alternative. The linear theory classifies possible political (or a-political) conditions by their degree of regimentation of the people by the state. Regimentation, of course, may vary from 0 to 100 per cent.

There is a footnote here that reads,

Democracy here appears to fall at about the 50 per cent level. Whether this is accurate (1 confess to having no idea) is not as important as the fact that democracy, having some regimentation, falls somewhere between the two extreme poles.

Back to the main text.

Mr. McGann, employing the linear theory, goes on to establish a graph of the “ideal" degree of state regimentation depending on one's subjective predilections for safety and freedom. The purpose of the present article is somewhat different, for it is to suggest the abandonment of the linear theory as well as the circular. Admittedly the linear theory, by its very nature, contains all political philosophies. Unfortunately, while quantity is gained by using it rather than the circular theory, some quality is lost. Clearly, the “left-right" division of political philosophies is not relevant in this construction. For example, fascists (extreme "rightists" as the term is used today) and communists ('leftists") would appear right next to each other, say at about 98 per cent and 99 per cent respectively.

There is a footnote here that reads,

I hereby propose the Hall theory of political regimentation: no matter how authoritarian, no system can be completely totalitarian for the simple reason that bureaucrats are too inefficient. Thus, 1 have left even communism with a 1 per cent "degree of freedom.”

Following the footnote, the main text reads,

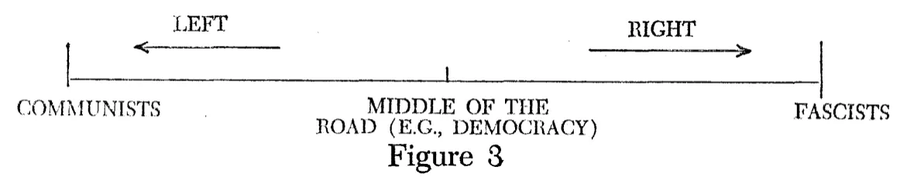

So too would individualist anarchists and collectivist anarchists appear together on the left side of the diagram. However, the former anarchists are closest in philosophy to John Locke and Adam Smith, while the latter are closest to Marx and the utopian socialists. Classifying these two anarchist groups together is rather absurd for they differ in their attitudes toward private property, certainly a fundamental political distinction. Perhaps, then, a left-right linear theory might be better (Figure 3) :

But alas, this is just the circular theory unbent; where are our anarchists? Certainly not on the right, but then neither on the left or in the center. Degrees of political regimentation have been sacrificed. It seems obligatory that we reject both linear and circular theories. Yet, if we are to have a plane geometric diagram of the political spectrum, the only choice seems to be a combination of lines and circles. At this stage, the author wishes to submit the "1opsided figure eight theory" of the political spectrum (Figure 4).

A footnote here reads

The author cautiously submits the L.F.E. theory as being original. However, he confesses to having done precious little research in the area of theories of political spectrum.

The main text continues,

This appears in the font of a graph, the Y-axis of which is "political regulation." For the collectivists, one might translate this as "well-intentioned guidance of all facets of an individual's life (e.g., cradle to grave) to ensure his happiness and security from pressures of the market place and from the pressures of choosing between political candidates-especially ones which might form an opposition to the present government."

A small d democrat would take this to mean "well-intentioned guidance of most facets of my neighbor's life to guarantee that he doesn't get any more handouts from the benevolent government (which we both support financially) than I do."

For the individualist, political regulation may be translated simply as "oppression of one man by another." On the X-axis, one finds "respect for private property." Many readers will question whether there can be a lack of respect for private property at the same time as there is a lack of political regulation, as does the author, but at least two political philosophies on the sample spectrum (Figure 4) seem to think this feasible.

Then a footnote,

This seems to be a totally inconsistent position but the collectivist anarchists, e.g., Bakunin, Kropotkin, Malatesta, Goldman, Berkman, etc., hold that the abolition of private property and its corollaries, capitalism and the wage-system, will lead to a communal society without government oppression. Similarly, fascists, while apparently interested in regimenting people as much as possible, pay lip service all the while to private property (restricted, of course, as may be necessary to meet the needs of the state) .

The main text goes on,

The L.F.E. theory combines the best of both circular and linear theories without their objectionable qualities. Overall political exploitation can be measured by a curve sloping downward and to the right, splitting the "eight" in half. So the higher and farther to the left a man's political condition, the more politically exploited he may expect to be. Low and far to the right indicates a position approaching pure objective freedom. “Rightists" in this context become “upper-halfists” and "leftists" are "lower-halfists."

Thus, in the main, political philosophies which are similar in fact (libertarians and individualist anarchists), similar in their conception of man and the state (conservatives and fascists), or similar in their modus operandi (fascists and communists) appear near each other on the figure. Furthermore, a line from the origin splitting the lopsided figure eight into two ovals serves quite well to separate the "'statist" from the "anti-statist" philosophies. This is useful not only for identifying various philosophies for their true nature but also to reveal what should be the distinction between left and right, e.g., statist versus anti-statist. But, as shown above, since the distinction is not in fact along these lines, the left-right linear theory must be found wanting.

Thus, the L.F.E. theory embodies the best of the linear political regimentation theory in the statist versus: anti-statist division and the best of the left-right linear and circular theories in the "upper-halfist" versus "lower-halfist" division. What then are the limitations of L.F.E. analysis? First, a logical point must be made. To say that the United States is next to Mexico and that Canada is next to the United States is, of course, correct. But we must remember that Canada is not next to Mexico. Similarly, socialism. is next to communism, which is next . to fascism on the diagram. But socialism and fascism can only be said to be similar in that they both are located on the statist oval. Second, some inaccuracies arise from putting a given philosophy actually on the eight rather than somewhere near it. For example, the collectivist anarchists appear farther right on the "respect for private property" axis than do conservatives. By definition collectivist anarchists are thoroughly opposed to private property so their position on the eight is inaccurate, but necessary since they are anti-statists. This suggests a criticism of any theory, including L.F.E., of the political spectrum. Models are designed to be representations in miniature of some phenomenon. In constructing a model, as great realism as possible must be strived for. Nevertheless, complete realism cannot be achieved "in miniature" because this is a contradiction in terms; complete realism comes only in the phenomenon itself. Therefore, any theory of the political spectrum is subject to inaccuracies. What is herein postulated may be treated as a more realistic inaccuracy.

Also in the Rampart Journal of Individualist Thought, Vol. IV', No. 2, Summer, 1968 is “Political Spectra and The Labels of Extremism” by D. O. Miles pages 32-39;

D.O. Miles is a physicist at the Lockheed Research Laboratories in Palo Alto, California. His field is experimental liquid-state physics, and he has authored numerous scientific papers on the results of his work. He also holds patents on scientific apparatus, and some of his inventions are presently being marketed. He wrote the following article during the heat of the Goldwater Johnson campaigns in 1964, "in response to inaccurate labeling which attended that contest."

Introduction

Complex ideas or phenomena are sometimes made. easier to understand if we can construct what scientists call a "model." If the model we construct is a good one, the various parts correspond to the parts of the complex idea or phenomenon. The resulting visualization is an aid to understanding. An example is the pendulum, which has long been employed to illustrate the tendency of human beings to overcompensate when taking corrective action against some trend deemed undesirable, Although the pendulum model is not perfect in all respects, it is very useful. Nearly everyone is familiar with the manner in which a pendulum in air repeatedly swings from one extreme position to another. Further, most people can appreciate how, if the pendulum were hung in a tank of molasses as a damping fluid, the pendulum might slowly approach the equilibrium position and stop with little or no overshoot. The proposed damping fluid tending to arrest or minimize oscillations in the case of society is, of course, governmental controls. The decision whether to employ a thin damping fluid like milk, or a very viscous one like cold tar, is made by experts such as social scientists, economists, and governmental officials.

The above brief discussion of the pendulum model serves to suggest how useful a model may be in stimulating thought and encouraging constructive controversy. Generations of Americans have been able to better comprehend economic and social problems by use of this model, and thus more intelligently contribute to the governmental processes. It is not intended, however, to pursue the pendulum model further. Our point is merely to state that, once a good model is constructed, our understanding of an otherwise obscure and complex phenomenon may be increased, our thoughts may be clarified, and enlightening discussion may ensue. Conversely, it must be cautioned, a poor model may not only fail to bring comprehension, but worse, give the illusion of comprehension while promoting a misconception.

The Linear Model of the Political Spectrum

Over the last decade, another model of an important phenomenon has become popular. We shall call this the linear model of the political spectrum. This is a geometrical model. In it, the range of governmental systems is displayed by positioning them along a line, as depicted in Figure 1. At the ends of the line are placed what is regarded as the two extreme opposites of politico-governmental systems in the world-communism at the left end, fascism at the right end. Between these extremes are more moderate forms of government, with democratic and representative forms being positioned near the center.

The linear model has some serious failings. Placing communism and fascism at opposite ends of the line is artificial. From the broad, overall viewpoint of governing systems, and from the viewpoint of the individual citizen as well, communism and fascism have much more in common than they have differences. Dominant in both is the overpowering superiority of the government as compared with the individual. "Der stat ist alles, der einziger ist nichtsn (the state is everything, the individual is nothing) differs very little from communism's submission of individual goals and initiative to those of the collective or group. The individual in either system faces the same iron-fisted environment. The difference that in fascism this absolute authority in all matters rests with one dictator, whereas in communism it rests with the central committee, is trivial. The employment of mass extermination to accomplish goals set by the government is common to both systems, as witnessed by the murder of 6,000,000 Jews in 1941-1945 by the German fascist government.

The footnote here is,

William Bridgwater and Seymour Kurtz (eds.), The Columbia Encyclopedia (New York: Columbia University Press, 1963), third ed., p. 1083.

Back to the main text,

and the murder of 3,000,000 Kulaks in 1932-1933 by the Russian communist government.

The footnote here is

Computed on the basis of excess deaths over normal for the Kulak fanners during the years 1932-33, by William H. Chamberlin, Russia's Iron Age (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1934), pp. 66-92.

Following the footnote,

The common end-point of extremism attained by both these systems is absolute, total authoritarianism on the part of the government, at the expense of all human rights and individual liberty.

If these systems are so similar, why are they then so antagonistic? Totalitarian governments, bent on conquest and motivated by fanatical zeal, even though they have much in common, can never trust each other, and seem always to come into conflict. The fact that fascism and communism have been at each other's throats does not in the least detract from their similarities as governmental systems.

Hence, we suggest that in any model of the political spectrum, fascism and communism be associated at the extreme of absolute governmental power, rather than separated. This immediately suggests what the opposite extreme point in our model should be. The opposite of absolute governmental power is no governmental power whatsoever. This is called anarchy. Thus, if we must employ a linear model of the political spectrum, let us think of the ends of the line as representing all-powerful government on the left; and no government at all on the right. Then, if citizens are in the middle of the line and move towards the left, they sacrifice individual rights in order to give government more power and control. If they move to the right, their government becomes weaker as more rights and responsibility devolve upon them as individuals. However, even this improvement in the linear model leaves much to be desired.

A Two-Dimensional Model

On a two-dimensional surface, let us, draw a circle as shown in Figure 2. At two diametrically opposite points we position the political opposites of anarchy (symbolically at the bottom of the circle) and absolute governmental power (symbolically at the top of the circle ).

In this model we perceive refinement sufficient to differentiate between Communism and fascism. Hence, the former is placed on the left side of the upper extreme, and the latter on the right side. What is the significance of this slight differentiation? The left half of the circle represents multi-n1an rule; the right half represents single-man rule. Thus, next to communism on the left, but further removed from totalitarianism, we place socialism with groups or committees of planners who exercise governmental control. Next to fascism on the right, we place monarchies. In general, then, as we proceed downwards around the left part of the circle in the direction of arrow (1), we encounter increasingly weaker multi-man rule systems. Arrow (2) on ,the right depicts increasingly weaker single-man rule systems. When, finally, the extreme of anarchy is reached, the arrows meet and all differences disappear due to the disappearance of governments.

The chief feature of the circle model is its graphic portrayal of the division of control between government and the individual citizen. The division existing in America today between governmental control and individual liberty could presumably be located on the circle. However, we could not decide whether to locate America's position on the right half or the left half of the circle, because ours is neither a multi-man nor a single-man rule system, but a mixture. Hence, the two-dimensional model is not geometrically complete enough to include our hybrid system.

The Three-Dimensional Model

We propose yet another degree of sophistication of the model for the political spectrum, as shown in Figure 3. Here, the model has become three-dimensional and is drawn isometrically as a sphere. Like the earth, it has two poles, which may be thought of as ice caps of extremism. The south pole represents anarchy. The north pole represents totalitarianism, or the absolute control by the government of each individual's actions.

The lines parallel to the equator mark differing degrees of sharing of control between individual citizens and their government. At the equator, half of all decisions would be made by the individual and the other half made for him. At the north pole, he could not even travel to the next city to visit relatives without filling out forms to obtain government permission. (This last statement would be humorous, were it not that some of the world's people have lived under governments where this very thing was demanded!)

Next, we call attention to the great meridian line passing through both poles. Along the left half of this meridian, labeled (1) in Figure 3, are positioned all purely multi-man rule governments. Along the right half, labeled (2) in Figure 3, are all purely single-man rule

governments. By deviating from the meridian line and proceeding into areas between, as shown by point A, we achieve any desired mixture between multi- and single-man rule.

An additional feature of the three-dimensional sphere model is that its size or radius may be varied for each government considered, to signify the technological and manpower resources available to said government.

Thus, the three-dimensional model as above proposed is a three variable system, with horizontal position (angle of longitude) achieving any degree of hybridization between multi- and single-man rule, vertical position (angle of latitude) depicting any degree of sharing of control between government and the individual, and spherical radius indicating the net resources behind the government.

Unless we have overlooked some other critical variable, any governmental system may be pictured in this model. If there are other variables not included, the next degree of sophistication of any geometrical model would require a four-dimensional surface. The utility of such a model would, however, be impaired due to our lack of ability to draw the model, build it out of plexiglass, or even to visualize it in the mind's eye.

Some Practical Implications of the Three-Dimensional Model

If the superiority of the three-dimensional over the presently accepted linear model be admitted, then certain changes in our thinking must follow. However, as will be pointed out below, these changes will not in the least discourage the sacred practice of name calling!

Most prominent among the changes called for by the three-dimensional model are alterations in categorizing the conservative and ultraconservative elements in America. It has become a world-wide practice to associate the American ultraconservative philosophy with fascism. This is a downright error, if we examine the improved model carefully. Do not misunderstand. We do not propose to remove the extremist label from the American ultraconservative. We simply wish to place the correct extremist label on him. He is not, as the fascism label would suggest, at the extreme of advocating an all powerful government. Indeed, the American ultraconservative is constantly saying, "Limit the power of government." Where he belongs is somewhere close to the extreme of no governmental power-of anarchy. Hence, it is suggested that ultraliberals henceforth hurl the epithet "anarchist" rather than "fascist" at their ultraconservative opponents. There is no danger in this of calming the tempest, for anarchist is considered to be just as dirty a word as fascist. It even sounds worse! Furthermore, it falls from the tongue with a more masculinely curse-like sound: an-ar-chist!

However, lest some liberal prefer his old ways of doing things and prove too unprogressive to adopt the new terminology, let us remind him that he himself has undoubtedly many times placed his conservative opponent in the camp of anarchy without realizing it. How many times has our intransigent liberal asked his conservative opponent, when arguing about government intervention in welfare, "Then you mean to say you would do nothing?" And the conservative probably had to admit that he would, indeed, have his government do absolutely nothing.

A footnote here reads,

There is good reason why the government should not step in, as is pointed out by Henry Grady Weaver, The Mainspring of Human Progress (New York: The Foundation for Economic Education, Inc., 1953), pp. 144, 145, 202.

Back to the main text,

The implication both of the question and the reply is of weak or inactive rather than powerful government-of anarchy rather than absolutism.

Thus, let ultraconservatives henceforth be called anarchists rather than fascists. This will detract not a whit from our fun, and it at least is a shade closer to the truth.

Be sure to see the other political spectrums, maps and so on through the Political Alignment Charts section of the Culture War Encyclopedia.

~ ∴ Ω ∴ ~

Justin Trouble

Culture War Encyclopedia on;

∴ Liberty ∴ Strength ∴ Honor ∴ Justice ∴ Truth ∴ Love ∴ Laughter ∴