This is part of a larger (upcoming) work on critical race theory in the Culture War Encyclopedia. Please share and subscribe.

CONTENTS

Short Version

Racial Realism is not Race Realism

Defining & Describing Racial Realism

Racial Realists vs Idealists in Critical Race Theory

Racial Realism Argues That Racial Equality Under the Law Only Provides Cover for Racism

Racial Realism Abandons the Goal of Racial Equality

Racial Realism from the Father of Critical Race Theory

From Legal Realism to Racial Realism

Relativism & Relativity in Racial Realism

Racial Realists Against Private Property Rights

Short Version

In the simplest terms, racial realism is the view that racial equality can never be achieved, at least not through law and that therefore other measures are needed than, for example, civil rights legislation. It is certainly not that simple, as we’ll see, but this is perhaps the closest one can come to a short definition of racial realism.

As the “intellectual father figure” of critical race theory,1 Derrick A. Bell Jr. wrote in the early 1990s,2 the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education, the Civil Rights Act, affirmative action and other measures can

do little more than bring about the cessation of one form of discriminatory conduct that soon appeared in a more subtle though no less discriminatory form

One might wonder if Professor Bell would also argue that the emancipation of slaves in America did little more than bring about more subtle but no less discriminatory racism. It was, after all, a legal matter, change grounded in law like the other legal acts that Bell wrote are not helpful. That is a sordid affair to which we will return later.

Racial Realism is not Race Realism

Be careful not to confuse racial realism with race realism which will have it’s own section in the Culture War Encyclopedia as soon as possible. A person who subscribes to racial realism would not likely subscribe to race realism. Race realism is commonly used in a derogatory manner to refer to the view that differences in human “races” are real and not social constructs.

Whereas race realism involves biological differences in between genetic groups of humans, racial realism is an attempt at being realistic with regard to the possibility of racial equality in our society

Defining & Describing Racial Realism

Racial realism is defined by critical race theorists Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic in the glossary of their book Critical Race Theory - an Introduction3 as the

view that racial progress is sporadic and that people of color are doomed to experience only infrequent peaks followed by regressions.

In 1992, the Connecticut Law Review printed Racial Realism by Derrick A. Bell Jr. in which he describes4 a movement of “blacks” who offer

a challenge to the principle of racial equality. This new movement is appropriately called Racial Realism, and it is a legal and social mechanism on which blacks can rely to have their voice and outrage heard.

We will return to that ahead. According to Basic Racial Realism, published by the Journal of the American Philosophical Association in 2015,

In the debate over the reality of race, a three-way dispute has become entrenched: race is biologically real, socially real, or simply not real. These three theses have each enjoyed increasingly sophisticated defenses over roughly the past thirty years, but we argue here that this debate contains a lacuna: there is a fourth, mostly neglected, position that we call ‘basic racial realism.’ Basic racial realism says that though race is neither biologically real nor socially real, it is real all the same.

The editors of Critical Race Theory - The Key Writings That Formed the Movement describe racial realism as pessimistic.5 We will see why this is so long before reaching the end.

Racial Realists vs Idealists in Critical Race Theory

In their book Critical Race Theory - An Introduction, in their chapter titled Hallmark Critical Race Theory Themes, Delgado and Stefancic write6 that the argument behind what some call racial realism is one that divides

critical race theory thinkers - indeed, civil rights activists in general. One camp, which we may call “idealists,” holds racism and discrimination are matters of thinking, mental categorization, attitude, and discourse. Race is a social construction, not a biological reality, they reason. Hence we may unmake it and deprive it of much of its sting by changing the system of images, words, attitudes, unconscious feelings, scripts, and social teachings by which we convey to one another that certain people are less intelligent, reliable, hardworking, virtuous, and American than others.

A contrasting school - the “realists” or economic determinists - holds that though attitudes and words are important, racism is much more than a collection of unfavorable impressions of members of other groups. For realists, racism is a means by which society allocates privilege and status. Racial hierarchies determine who gets tangible benefits, including the best jobs, the best schools, and invitations to parties in people’s homes. Members of this school of thought point out that antiblack prejudice sprang up with slavery and capitalists’ need for labor. Before then, educated Europeans held a generally positive attitude toward Africans, recognizing that African civilization were highly advanced with vast libraries and centers of learning. Indeed, North Africans pioneered mathematics, medicine, and astronomy long before Europeans had much knowledge of these disciplines.

Materialists point out that conquering nations universally demonize their subjects to feel better about exploiting them, so that, for example, planters and ranchers in Texas and the Southwest circulated notions of Mexican inferiority at roughly the same period that they found it necessary to take over Mexican lands or, later, to import Mexican people for backbreaking labor. For materialists, understanding the ebb and flow of racial progress and retrenchment requires a careful look at conditions prevailing at different times in history. Circumstances change so that one group finds it possible to seize advantage or to explore another. They do so and then form appropriate collective attitudes to rationalize what was done. Moreover what is true for subordination of minorities is also true for its relief: civil rights gains for communities of color coincide with the dictates of white self-interest. Little happens out of altruism alone

In the early years of critical race theory, the realists were in a large majority. For example, scholars questioned whether the much-vaunted system of civil rights remedies ended up doing people of color much good. In a classic article in Harvard Law Review, Derrick Bell argued that civil rights advances for blacks always seemed to coincide with changing economic conditions and the self-interest of elite whites. Sympathy, mercy, evolving standards of social decency and conscience amounted to little, if anything.

We’ll look at this classic article ahead. Bell, as we’ll see, is an example of a scholar who

questioned whether the much-vaunted system of civil rights remedies ended up doing people of color much good.

Racial Realism Argues That Racial Equality Under the Law Only Provides Cover for Racism

In his argument for racial realism, Derrick A. Bell Jr. writes,7

As every civil rights lawyer has reason to know - despite law school indoctrination and belief in the "rule of law"- abstract principles lead to legal results that harm blacks and perpetuate their inferior status.

Notice the theme or sub-argument within the racial realist argument that racial equality under the law only allows subtle racism to continue unabated. Earlier we saw how Bell wrote that legal remedies for racial inequality

do little more than bring about the cessation of one form of discriminatory conduct that soon appeared in a more subtle though no less discriminatory form

In this vein, Dino Franco Felluga writes in Critical Theory - The Key Concepts (2015)8 that from the view of critical race theory,

a legal notion of equality that is “color-blind,” purporting to provide the same opportunities to everyone regardless of race, gender, sexual orientation, and so on, only addresses “the most blatant form of discrimination, such as mortgage redlining or refusal to hire a black Ph.D. rather than a white high school dropout, that do stand out and attract our attention” (7). According to CRT, the liberal doctrine of “color blind” equality (e.g. the principle of meritocracy, which is used to reject affirmative-action rules) in fact serves to legitimate all the other forms of oppression and marginalization that constitute the daily experience of suburban racial, gender, and sexual identity. The law’s support pf color-blind equality thus keeps dominant identity groups from having to address the real, everyday injustices or even the systemic mechanisms (e.g., standardized tests, police profiling, legal precedence) that deny subaltern groups power, status, respect, and wealth. One way that CRT scholars seek to reveal daily, common forms of racism is through “legal storytelling,” the recounting of personal culture, or through alternative histories that retell the history of civil rights legislation from the less triumphalist and always suspicious perspective of subaltern identities, as in Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States (1999) or Derrick A. Bell Jr.’s recounting of the real (and secret) governmental impetus behind Brown v. Board of Education.

In Racial Realism, Professor Bell writes9 that the gaining of the legal right to equality only traded open racial bias for hidden racial bias.

Black people will never gain full equality in this country. Even those herculean efforts we hail as successful will produce no more than temporary "'peaks of progress," short-lived victories that slide into irrelevance as racial patterns adapt in ways that maintain white dominance. This is a hard-to-accept fact that all history verifies. We must acknowledge it and move on to adopt policies based on what I call: "Racial Realism." This mind-set or philosophy requires us to acknowledge the permanence of our subordinate status. That acknowledgement enables us to avoid despair, and frees us to imagine and implement racial strategies that can bring fulfillment and even triumph.

Legal precedents we thought permanent have been overturned, distinguished, or simply ignored. [28] All too many of the black people we sought to lift through law from a subordinate status to equal opportunity, are more deeply mired in poverty and despair than they were during the "Separate but Equal" era.

Despite our successful effort to strip the law's endorsement from the hated "Jim Crow" signs, contemporary color barriers are less visible but neither less real nor less oppressive. Today, one can travel for thousands of miles across this country and never come across a public facility designated for "Colored" or "White." Indeed, the very absence of visible signs of discrimination creates an atmosphere of racial neutrality [29] that encourages whites to believe that racism is a thing of the past.

Today, blacks experiencing rejection for a job, a home, a promotion, anguish over whether race or individual failing prompted their exclusion. Either conclusion breeds frustration and eventually despair. We call ourselves African Americans, but despite centuries of struggle, none of us-no matter our prestige or position-is more than a few steps away from a racially motivated exclusion, restriction or affront.

There is little reason to be shocked at my prediction that blacks will not be accepted as equals, a status which has eluded us as a group for more than 300 years. The current condition of most blacks provides support for this position.[30] It is surely possible to use statistics to distort, and I do wish for revelations showing that any of the dreadful data illustrating the plight of so many black people is false or misleading. But there is little effort to discredit the shocking disparities contained in these reports. Even so, the reports have little effect on policy-makers or the society in general.

Statistics and studies reflect racial conditions that transformed the "We Have a Dream" mentality of the 1960s into the trial by racial ordeal so many blacks are suffering in the 1990s. The adverse psychological effects of nonexistent opportunity are worse than the economic and social loss. As the writer, Maya Angelou, put it recently:

In these bloody days and frightful nights when an urban warrior can find no face more despicable than his own, no ammunition more deadly than self-hate and no target more deserving of his true aim than his brother, we must wonder how we came so late and lonely to this place.[31]

As a veteran of a civil rights era that is now over, I regret the need to explain what went wrong. Clearly we need to examine what it was about our reliance on racial remedies that may have prevented us from recognizing that these legal rights could do little more than bring about the cessation of one form of discriminatory conduct that soon appeared in a more subtle though no less discriminatory form. The question is whether this examination requires us to redefine goals of racial equality and opportunity to which blacks have adhered for more than a century.

The answer, must be a resounding "yes."

Traditional civil rights law is highly structured and founded on the belief that the Constitution was intended -at least after the Civil War Amendments- to guarantee equal rights to blacks. The belief in eventual racial justice, and the litigation and legislation based on that belief, was always dependent on the ability of believers to remain faithful to their creed of racial equality, while rejecting the contrary message of discrimination that survived their best efforts to control or eliminate it.

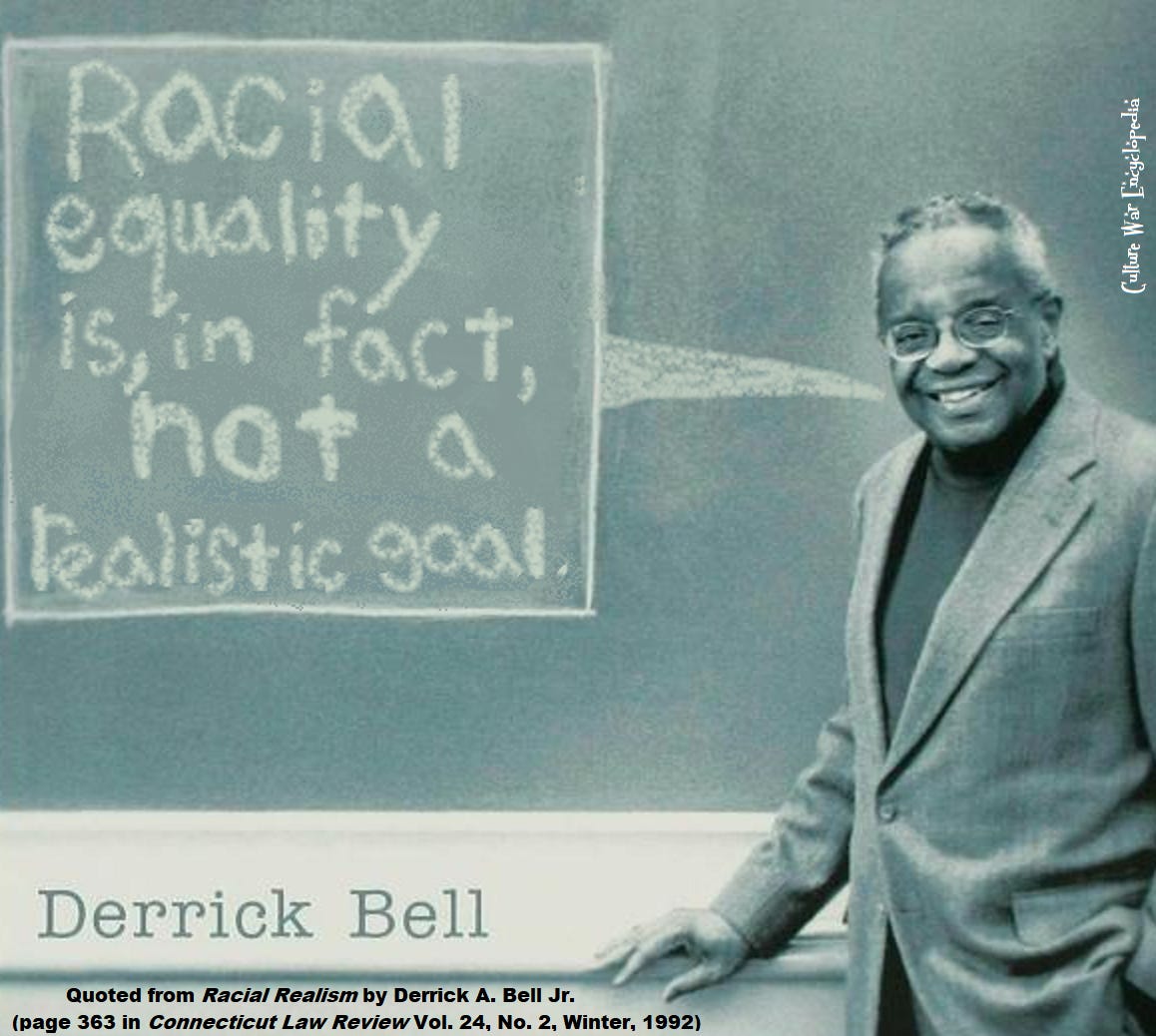

Racial Realism Abandons the Goal of Racial Equality

From the grave, the late but ever-pleasant Professor Bell offers this ray of sunshine,10

Racial equality is, in fact, not a realistic goal. By constantly aiming for a status that is unobtainable in a perilously racist America, black Americans face frustration and despair. Over time, our persistent quest for integration has hardened into self-defeating rigidity.

Note that Professor Bell is the first named by Angela Harris among the “major intellectual figures” at the first workshop on critical race theory in 1989 along with Kimberle Crenshaw, Richard Delgado, Mari Matsuda and Patricia Williams.11 One of these so named major intellectual figures of critical race theory, Richard Delgado himself, along with Jean Stefancic write that Derrick Bell is the “intellectual father figure” of critical race theory.12 Unlike any other author included in Critical Race Theory - The Key Writings That Formed the Movement 3 of the 27 essays were written by Derrick A. Bell Jr.13 who urges us to give up on the goal of equal treatment under the law, to give up on the color blind ideal for law.

Remember, Lady Justice is blindfolded for a reason. Justice must be blind, and along with that general blindness (impartiality) comes color blindness (race-neutrality). But good Sir Derrick A. Bell Jr., Esquire would have us give up on justice.

This is not to say that all crits are totally pessimistic about racial equality. In Race in the 21st Century: Equality Through Law (1990),14 Professor Linda Sheryl Greene does not use the term racial realism, but she does argue that the “realistic” view is that racial quality can not be gained through legal measures, almost surely.

Her essay is included by the editors of Critical Race Theory - The Key Writings That Formed the Movement right before Bell’s Racial Realism. Though these editors characterize her essay as pessimistic, along with Bell’s,15 Greene acknowledges the possibility of racial equality.16 Perhaps we can consider Greene a soft realist or a pseudo realist if we allow that racial realism means dropping all hope for racial equality, as we’ll see Bell argue.

At any rate, not crits are hard realists, as I’ll characterize Bell, and not all crits are realists at all as we’ll see ahead.

Racial Realism from the Father of Critical Race Theory

As mentioned, Bell is considered an intellectual parent of critical race theory. One of the 3 essays by Bell that the editors of Critical Race Theory - The Key Writings That Formed the Movement (1995)17 include in their canon (so to speak) is Racial Realism. It had originally been printed printed in The Connecticut Law Review in 1992.18 In this essay, Bell's message is not exactly clear. He argues that racial equality under the law does not decrease racism or racial inequality but merely converts official and open racism into unofficial and hidden racism. Furthermore, he argues that racial equality can never be obtained. It is no wonder, then, that the editors described Bell’s message in Racial Realism as pessimistic.19

Though he describes racial realism as he sees it and offers it as a solution, his message remains vague and confusing. The very idea of racial realism as a solution to racism appears to be nonsense since racial realism means giving up on the goal of racial equality. That’s more of an admission of failure than it is a solution, is it not?

One thing Bell makes clear is that he thinks racial equality can never be obtained and that therefore people should stop trying to gain it. Then again, his conclusions strongly implies that people should never give up the eternal struggle for this unobtainable goal. We will do our best here to summarize and analyze Bell’s difficult Racial Realism, however, we recommend reading the entire essay yourself here.

He states near the beginning of Racial Realism that the eternal struggle for racial equality is “frustrating”, defeating and gives people “despair”.20 In the middle he writes, as you will recall from above, that racial equality will never be achieved and that, that this realization is racial realism and that

That acknowledgement enables us to avoid despair, and frees us to imagine and implement racial strategies that can bring fulfillment and even triumph.

Avoid despair? This is curious because he concludes with what seems to be a recommendation of finding solace in engaging in endless struggle for unobtainable racial equality.21 So which is it? Does this eternal struggle give one joy and meaning as he we’ll see him imply, or frustration, despair and defeat?

Bell seems to be contradicting himself or otherwise expecting the reader to connect his dots to come to some unstated message that would render his message coherent, some key to unlock the inscrutable meaning or a missing puzzle piece to make sense of his otherwise absurd (even if, as we’ll come to, absurdist) essay. Perhaps he wrote this to amuse himself over the confusion it might cause and the late Professor Derrick A. Bell Jr., Esq. mocks at us from his grave.

He begins,22

The struggle by black people to obtain freedom, justice, and dignity is as old as this nation. At times, great and inspiring leaders rose out of desperate situations to give confidence and feelings of empowerment to black community. Most of these leaders urged their people to strive for racial equality. They were firmly wedded to the idea that the courts and judiciary were the idea that the social position of blacks. In spite of dramatic civil rights movements and periodic victories in the legislatures, black Americans by no means are equal to whites. Racial equality is, in fact, not a realistic goal. By constantly aiming for a status that is unobtainable in a perilously racist America, black Americans face frustration and despair. Over time, our persistent quest for integration has hardened into self-defeating rigidity.

Note in that quote where he writes of defeat and despair. He then compares racial realism to legal realism stating that23

Black people need reform of our civil rights strategies as badly as those in the law needed a new way to consider American jurisprudence prior to the advent of the Legal Realists. [1]

who, he writes,24 challenged the “entire jurisprudential system.” He writes25 that "Reliance on rigid application of the law" that is "done for the sake of ending discriminatory racial practices" is "damaging" and "ineffectual".

He writes26 that the legal realists attacked

the whole liberal worldview of private rights and public sovereignty mediated by rule of law needed to be exploded. The Realists argued that a worldview premised on the public and private spheres is an attractive mirage that masks the reality of economic and political power.

Read Bell’s Racial Realism yourself and see how often he declares the hopelessness of attaining racial equality. Also note his repeated anti-private property messages.

He concludes with a description of the efforts of a woman he knew in his younger days, Mrs. MacDonald to organize to ensure that a court order mandating desegregation of their local schools was implemented despite all the pushback she had to struggle against. He writes,27

I asked where she found the courage to continue working for civil rights in the face of intimidation that included her son losing his job in town, the local bank trying to foreclose on her mortgage, and shots fired through her living room window. "Derrick," she said slowly, seriously, "I am an old woman. I lives to harass white folks."

Mrs. MacDonald did not say she risked everything because she hoped or expected to win out over the whites who, as she well knew, held all the economic and political power, and the guns as well. Rather, she recognized that-powerless as she was-she had and intended to use courage and determination as weapons "to harass white folks." Her fight, in itself, gave her strength and empowerment in a society that relentlessly attempted to wear her down. Mrs. MacDonald did not even hint that her harassment would topple whites' well-entrenched power. Rather, her goal was defiance and its harassing effect was more potent precisely because she placed herself in confrontation with her oppressors with full knowledge of their power and willingness to use it.

Mrs. MacDonald avoided discouragement and defeat because at the point that she determined to resist her oppression, she was triumphant. Nothing the all-powerful whites could do to her would diminish her triumph. Mrs. MacDonald understood twenty-five years ago the theory that I am espousing in the 1990s for black leaders and civil rights lawyers to adopt. If you remember her story, you will understand my message.

Is that so? One can understand her story and yet have questions. Do you understand his message? If so, please help me to understand how/why Bell can argue that racial inequality is impossible to ever overcome, that the endless struggle to obtain it is defeating and despairing and also argue that people should engage in that struggle anyway. Yes, in the absurdist view, as Albert Camus wrote28 that like Sisyphus in his eternal struggle against Gods and gravity, forever sentenced to push a stone up a hill because it always rolls back down, one can find fulfillment in struggle without resolution because,

The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.

I, for one, can sympathize with Camus, his Sisyphus and with Bell’s spirit of spite and spitfire and the fight, with burning heart, against that which holds us back. But that is my love, my passion and my choice. Others are not born to fight, do not wish to fight and want to have what they fight rather than to fight for it. Many are too busy raising families or just trying to survive. At any rate, people deserve resolutions to injustice. Bell offers no such thing. We can see why Delgado and Stefancic write in Critical Race Theory - An Introduction29 that

Bell’s article evoked outrage and accusations of cynicism.

Still, as we say Delgado and Stefancic write earlier Bell was a realist and the realists were in the “large majority” in the early years of critical race theory.30

If racial equality under the law is to be rejected, what do Bell or any of the crits have to offer as an alternative? Bell’s conclusion quoted above seems to imply that the answer is to fight forever for racial quality. Why then, one must ask, the opposition to legal measures? Even if they are not sufficient to cure all racism, does it help to oppose civil rights gains?

As we saw, their argument is that these legal gains were not gains, but merely cloaks that allowed racism to continue to the same degree just in less obvious forms. What, then, is the solution?

It is difficult to ignore that critical race theorists argue for racial separatism. This seems to be the only answer offered by CRT. Laws for racial equality would not be needed in racially homogenous nation. It seems reasonable to conclude, and it would make sense in a horrible way, to say that critical race theory opposes racial equality under the law as a solution for racial inequality because it wants racially separate nations instead (see Race Consciousness & Racial Separatism in Critical Race Theory).

Note that critical race theory is considered to be a branch of critical legal studies which is a branch of critical theory and that all of these are what they themselves have called cultural Marxism for many decades now. Note that these are openly neo-Marxist, meaning that rather than the struggle of the classes to bring about the (college student and professor led) ‘workers revolution’ to overthrow capitalism, they drive encourage the struggle of identity groups such as ‘races’ and arguing for such things, as critical race theory does, as racial separatism to accelerate the cultural revolution against capitalism, whiteness, rights and so on (see the section on critical race theory).

Certainly most members of the wider public who support critical race theory are not aware of this aspect of CRT. It is not, however, some big secret. At any rate, if not one single crit were aware of the history of their own movement (which seems extremely unlikely), the fact is that CRT works as if it were designed to drive division in Western culture. Intended or not, CRT swaps out the war of the classes with the war of the ‘races’.

Perhaps this is the key, the missing piece of the puzzle with Bell’s Racial Realism essay.

From Legal Realism to Racial Realism

We have already seen some of what Bell had to say about the relation between legal realism and racial realism. Here is more context. Bell writes,31

Black people need reform of our civil rights strategies as badly as those in the law needed a new way to consider American jurisprudence prior to the advent of the Legal Realists.[1] By viewing the law -and by extension, the courts- as instruments for preserving the status quo and only periodically and unpredictably serving as a refuge of oppressed people, blacks can refine the work of the Realists. Rather than challenging the entire jurisprudential system, as the Realists did, blacks' focus must be much narrower - a challenge to the principle of racial equality. This new movement is appropriately called Racial Realism, and it is a legal and social mechanism on which blacks can rely to have their voice and outrage heard.

Reliance on rigid application of the law is no less damaging or ineffectual simply because it is done for the sake of ending discriminatory racial practices. Indeed, Racial Realism is to race relations what "Legal Realism" is to jurisprudential thought. The Legal Realists were a group of scholars in the early part of the twentieth century who challenged the classical structure of law as a formal group of common-law rules that, if properly applied to any given situation, lead to a right - and therefore just - result.[2] The Realists comprised a younger generation of scholars -average age forty-two[3]- who were willing to challenge what they viewed as the rigid ways of the past. More than their classical counterparts, they had been influenced by the rapid spread of the scientific outlook and the growth of social sciences. Such influence predisposed the Realists to accept a critical and empirical attitude towards the law,[4] in contrast to the formalists who insisted that law was logically self-evident, objective, a priori valid, and internally consistent. The great majority of the movement's pioneers had practical experience which strengthened their awareness of the changing and subjective elements in the legal system. This awareness flew in the face of the Langdellian conception of law as unchanging truth and an autonomous system of rules."[5]

Bell goes on to describe, it seems fair to say, a somewhat deconstructionist approach to jurisprudence from “the Realists”, scholars32 as opposed to their

classical counterparts

whom Bell refers to as

the formalists who insisted that law was logically self-evident, objective, a priori valid, and internally consistent.

Their time, so to speak, was in the 1930s and 1940s according to the editors of Critical Race Theory - Key Writings That Formed the Movement.33 Returning to Bell’s essay,34

The Realists took their cue from Oliver Wendell Holmes who staged a fifty year battle against legalistic formalism

and who argued that judges do not make rational rulings, but rather relied on

value-laden, personal beliefs. . . beliefs which, like all moral values, were wholly relative

Relativism & Relativity in Racial Realism

As we saw, according to Bell, legal realism and racial realism take a relativistic approach as opposed to a classical or formal approach. Relativism is defined in epistemology35 as

The view that all truths are subjective - that my idea of truth (say, that dead people can’t talk to the living) will not necessarily be held by someone else who is a product of a different belief system. Epistemological relativism maintains that ideas are manufactured by language, history, and cultural conventions and cannot be held to any objective, universal standards. . .

In ethics and morality, relativism is the notion that ideas of the good and the bad, the just and the unjust, the desirable and the undesirable differ from place to place and people to people, and that moral judgements should thus be withheld.

In A Comparative History of Ideas, author Hajime Nakamura includes relativism36 as a subsection of skepticism.37 He writes,38

If we, admitting the significance of skepticism in any sense, want to justify our actions in any way, we shall be led to the standpoint of relativism. Relationistic doctrines were clearly represented in Jainism in India and by some thinkers in Greece.

The fundamental standpoint of Jainism is logically called “The Maybe Theory” (syadvada).[1] It signifies that the universe can be looked at from many points of view, and that each viewpoint yields a different conclusion (anekanta). Therefore no conclusion is decisive.

Just as relativism stands in contrast to classical views which maintain objective standards by which to view things, in physics, the theory of relativity stands in contrast to classical physics. As Arthur Goldwag writes,39

That said, relativity acknowledges that it is impossible to measure “absolute motion” - measurements of motion made from within a moving system will be different from measurements of the same motion made from within it. Even so, both measurements will be correct.

Similarly, legal realism, as Bell describes it, takes a relativist approach to case law in contrast to the classical or formalistic approach.

Racial Realists Against Private Property Rights

Bell also writes40

Realist notions also were grounded in the views of the Progressives during the 1890s. Concerned with social welfare legislation and administrative regulation, the Progressives criticized the conceptualization of property rights being expounded by the United States Supreme Court.[7] Creating a remedy based upon the finding of a property right was the Court's way of subtly imposing personal and moral beliefs. . .

The Realists also had a profound impact by demonstrating the circularity of defining rights as "objective," which definition depended, in large part, on a distinction between formalistically bounded spheres between public and private.[9] Classical judges justified decisions by appealing to these spheres. For example, an opinion would justify finding a defendant liable because she had invaded the (private) property rights of the plaintiff. But such a justification, the Realists pointed out, was inevitably circular because there would be such a private property right if, and only if, the court found for the plaintiff or declared the statute unconstitutional. The cited reasons for decisions were only results, and as such served to obscure the extent to which the state's enforcement power through the courts lay behind private property and other rights claims.[10]

In Racial Realism, Bell also writes,41

The Realists also had a profound impact by demonstrating the circularity of defining rights as “objective,” which definition depended, in large part, on a distinction between formalistically bounded spheres between public and private. [9] Classical judges justified decisions by appealing to these spheres. For example, an opinion would justify finding a defendant liable because she had invaded the (private) property rights of the plaintiff. But such a justification, the Realists pointed out, was inevitably circular because there would be such a private property right if, and only if, the court found for the plaintiff or declared the statute unconstitutional. The cited reasons for decisions were only results, and as such served to obscure the extent to which the state's enforcement power through the courts lay behind private property and other rights claims. [10]

Further on, he writes,42 that

the Realists' critique suggested that the whole liberal worldview of private rights and public sovereignty mediated by the rule of law needed to be exploded. The Realists argued that a worldview premised upon the public and private spheres is an attractive mirage that masks the reality of economic and political power.

It should hardly be surprising that critical race theory should challenge the right to private property when we consider that it is rooted in critical legal studies, critical theory and cultural Marxism.

Also see:

critical race theory (coming soon)

critical theory (coming soon)

Implicit Association Test (IAT)

interest convergence (coming soon)

racial separatism in critical race theory

SOURCES

Bell Jr., Derrick A. - Racial Realism - Connecticut Law Review Vol. 24, No. 2 (Winter, 1992); reprinted in Critical Race Theory - The Key Writings That Formed the Movement (copyright 1995, the New Press)

Delgado, Richard and Jean Stefancic - Critical Race Theory - an Introduction (3rd edition, 2017) New York University Press

Felluga, Dino Franco - Critical Theory - The Key Concepts (2015) Routledge Taylor & Francis Group

Glasgow, Joshua and Jonathan Woodward - Basic Racial Realism - Journal of the American Philosophical Association , Volume 1 , Issue 3 , Fall 2015 , pp. 449 - 466 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/apa.2015.7, published online by Cambridge University Press (2015)

Goldwag, Arthur - Isms and Ologies - Quercus (2007)

Greene, Linda Sheryl - Race in the 21st Century: Equality Through Law - Tulane Law Review, Volume 64, Issue 6 (1990)

Nakamura, Hajime - A Comparative History of Ideas - second Indian edition (no date); first Indian edition, 1992, copyright Hajime Nakamura, 1975, 1986.

(multiple authors, forward by Cornel West, edited by Kimberle Crenshaw, Neil Gotanda, Gary Peller, Kendell Thomas) - Critical Race Theory - The Key Writings That Formed the Movement (copyright 1995, the New Press)

∴ Liberty ∴ Strength ∴ Honor ∴ Justice ∴ Truth ∴ Love ∴ Laughter ∴

Page 6 in Critical Race Theory - An Introduction by Delgado & Stefancic

Page 183 in Critical Race Theory - an Introduction by Delgado & Stefancic

Page 202 in Critical Race Theory - The Key Writings That Formed the Movement by the editors.

Pages 365-367 in Connecticut Law Review Vol. 24. No. 2 (Winter, 1992)

Pages 62-63 in Critical Theory - The Key Concepts by Dino Franco Felluga

Pages 373-376 in Connecticut Law Review Vol. 24, No. 2 (Winter, 1992)

Page XV, Harris, Angela, Forward to Delgado, Richard and Jean Stefancic - Critical Race Theory - an Introduction (3rd edition, 2017) New York University Press

(multiple authors, forward by Cornel West, edited by Kimberle Crenshaw, Neil Gotanda, Gary Peller, Kendell Thomas) - Critical Race Theory - The Key Writings That Formed the Movement (copyright 1995, the New Press)

Race in the 21st Century: Equality Through Law, Linda Greene

Page 202 in Critical Race Theory - The Key Writings That Formed the Movement

Page 300 in Critical Race Theory - The Key Writings That Formed the Movement

Pages 302-312 in Critical Race Theory - The Key Writings That Formed the Movement by multiple authors, forward by Cornel West, edited by Kimberle Crenshaw, Neil Gotanda, Gary Peller, Kendell Thomas

Bell Jr., Derrick A. - Racial Realism - Connecticut Law Review Vol. 24, No. 2 (Winter, 1992)

Page 202 in Critical Race Theory - The Key Writings That Formed the Movement

Page 363 in Connecticut Law Review Vol. 24. No. 2 (Winter, 1992), page 302 in Critical Race Theory - The Key Writings That Formed the Movement (1995)

Pages 378-379 in Connecticut Law Review Vol. 24, No. 2, Winter 1992; Pages 308-309 in Critical Race Theory - The Key Writings that Formed the Movement

Page 363 in Connecticut Law Review Vol. 24, No. 2, Winter 1992; Page 302 in Critical Race Theory - The Key Writings that Formed the Movement

Pages 363-634 in Connecticut Law Review Vol. 24, No. 2, Winter 1992; Page 302 in Critical Race Theory - The Key Writings that Formed the Movement

Page 364 in Connecticut Law Review Vol. 24, No. 2, Winter 1992; Page 302 in Critical Race Theory - The Key Writings that Formed the Movement

Page 364 in Connecticut Law Review Vol. 24, No. 2, Winter 1992; Page 302 in Critical Race Theory - The Key Writings that Formed the Movement

Page 367 in Connecticut Law Review Vol. 24, No. 2, Winter 1992; Page 303 in Critical Race Theory - The Key Writings that Formed the Movement

Pages 378-379 in Connecticut Law Review Vol. 24, No. 2, Winter 1992; Pages 308-309 in Critical Race Theory - The Key Writings that Formed the Movement

See page 78 in The Myth of Sisyphus And Other Essays by Albert Camus (1955)

Page 23 in Critical Race Theory - an Introduction by Delgado and Stefancic

Page 22 in Critical Race Theory - An Introduction by Delgado and Stefancic

Pages 363-365 in Connecticut Law Review Vol. 24, No. 2 (Winter, 1992)

Page 364-365 in Connecticut Law Review Vol. 24, No. 2 (Winter, 1992)

Page 203 in Critical Race Theory - Key Writings That Formed the Movement

Page 364-365 in Connecticut Law Review Vol. 24, No. 2 (Winter, 1992)

Pages 124-125 in Isms and Ologies by Arthur Goldwag

Page 167 in A Comparative History of Ideas by Hajime Nakamura

Page 162 in A Comparative History of Ideas by Hajime Nakamura

Page 167 in A Comparative History of Ideas by Hajime Nakamura

Page 169 in Isms and Ologies by Arthur Goldwag

Pages 365-367 in Connecticut Law Review Vol. 24, No. 2 (Winter, 199)

Page 366-367 in Connecticut Law Review Vol. 24, No. 2, Winter 1992; Page 303 in Critical Race Theory - The Key Writings that Formed the Movement

Page 367 in Connecticut Law Review Vol. 24, No. 2, Winter 1992; Page 303 in Critical Race Theory - The Key Writings that Formed the Movement