speciesism

CONTENTS

Simple Definitions

1970 - ‘Speciesism’ is Coined, Defined & Written About

1983/1986 - ‘Speciesism’ Gains Currency

1985 - ‘Speciesism’ is Added to the Oxford English Dictionary

2002 - ‘Speciesism’ Compared to Racism, Sexism & Classism

2019 - Matsouka & Sorenson Carry on the Torch

Simple Definitions

Speciesism . . . is a prejudice or attitude of bias in favor of the interests of members of one’s own species and against those of members of other species.

according the book Animal Liberation (1970) by Peter Singer who, as we’ll see, apparently coined the term.

Speciesism is

discrimination against or exploitation of certain animal species by human beings, based on an assumption of mankind’s superiority

as the term first appeared in the Oxford English Dictionary in1985 according to David Nibert.

Speciesism is

systematic discrimination based on species membership

according to A case for animal rights by T. Regan (1986).

Speciesism is also the view that only humans have “inherent value” or that the only right species is our own, according to Regan in the same work.

Speciesism is

an ideology, a belief system that legitimizes and inspires prejudice and discrimination.

according to David Nibert (2002).

According to A. Matsouka and J. Sorenson (2019),

Speciesism = practice of assigning value to beings based solely on membership in a particular species.

We will return to all the above with more context and more precise citation below.

1970 - ‘Speciesism’ is Coined, Defined & Written About by Ryder

‘Speciesism’, as a term, was devised by Richard Ryder in 1970

who characterized it as a form of prejudice that prioritized human interests over those of nonhuman animals. Ryder described this prejudice as being similar to racism and sexism. All of these prejudices are based on morally irrelevant differences, exaggerating them and overlooking similarities in order to disregard the suffering of others.

This is according to Matsuoka and Sorenson in What is Critical Animal Studies? for Animals and Social Work, June 2019. Speciesism, they write, is our justification of the oppression of nonhuman animals.

1975 saw the publication of Animal Liberation by Peter Singer in which he wrote of speciesism. In Chapter 1, page 28, headed,

All Animals Are Equal … or why the ethical principle on which human equality rests requires us to extend equal consideration to animals too

In this chapter, Singer makes

the case for the equality of animals

and argues (on page 34) that it is out of a

principle of equality that our concern for others and our readiness to consider their interests ought not to depend on what they are like or on what abilities they may possess. Precisely what our concern or consideration requires us to do may vary according to the characteristics of those affected by what we do:

He writes (pages 34-35) about Thomas Jefferson and Sojourner Truth arguing for equality of races and sexes and then argues (pages 35-36),

It is on this basis that the case against racism and the case against sexism must both ultimately rest; and it is in accordance with this principle that the attitude that we may call “speciesism,” by analogy with racism, must also be condemned. Speciesism—the word is not an attractive one, but I can think of no better term—is a prejudice or attitude of bias in favor of the interests of members of one’s own species and against those of members of other species. It should be obvious that the fundamental objections to racism and sexism made by Thomas Jefferson and Sojourner Truth apply equally to speciesism. If possessing a higher degree of intelligence does not entitle one human to use another for his or her own ends, how can it entitle humans to exploit nonhumans for the same purpose?4

Many philosophers and other writers have proposed the principle of equal consideration of interests, in some form or other, as a basic moral principle; but not many of them have recognized that this principle applies to members of other species as well as to our own. Jeremy Bentham was one of the few who did realize this. In a forward-looking passage written at a time when black slaves had been freed by the French but in the British dominions were still being treated in the way we now treat animals, Bentham wrote:

The day may come when the rest of the animal creation may acquire those rights which never could have been withholden from them but by the hand of tyranny. The French have already discovered that the blackness of the skin is no reason why a human being should be abandoned without redress to the caprice of a tormentor. It may one day come to be recognized that the number of the legs, the villosity of the skin, or the termination of the os sacrum are reasons equally insufficient for abandoning a sensitive being to the same fate. What else is it that should trace the insuperable line? Is it the faculty of reason, or perhaps the faculty of discourse? But a full-grown horse or dog is beyond comparison a more rational, as well as a more conversable animal, than an infant of a day or a week or even a month, old. But suppose they were otherwise, what would it avail? The question is not, Can they reason? nor Can they talk? but, Can they suffer? 5

He writes on page 50,

The belief that human life, and only human life, is sacrosanct is a form of speciesism.

On pages 51-52, Singer writes,

The only thing that distinguishes the infant from the animal, in the eyes of those who claim it has a “right to life,” is that it is, biologically, a member of the species Homo sapiens, whereas chimpanzees, dogs, and pigs are not. But to use this difference as the basis for granting a right to life to the infant and not to the other animals is, of course, pure speciesism.14 It is exactly the kind of arbitrary difference that the most crude and overt kind of racist uses in attempting to justify racial discrimination.

This does not mean that to avoid speciesism we must hold that it is as wrong to kill a dog as it is to kill a human being in full possession of his or her faculties. The only position that is irredeemably speciesist is the one that tries to make the boundary of the right to life run exactly parallel to the boundary of our own species. Those who hold the sanctity of life view do this, because while distinguishing sharply between human beings and other animals they allow no distinctions to be made within our own species, objecting to the killing of the severely retarded and the hopelessly senile as strongly as they object to the killing of normal adults.

To avoid speciesism we must allow that beings who are similar in all relevant respects have a similar right to life—and mere membership in our own biological species cannot be a morally relevant criterion for this right. Within these limits we could still hold, for instance, that it is worse to kill a normal adult human, with a capacity for self-awareness and the ability to plan for the future and have meaningful relations with others, than it is to kill a mouse, which presumably does not share all of these characteristics; or we might appeal to the close family and other personal ties that humans have but mice do not have to the same degree; or we might think that it is the consequences for other humans, who will be put in fear for their own lives, that makes the crucial difference; or we might think it is some combination of these factors, or other factors altogether.

On page 73, he writes,

The practice of experimenting on nonhuman animals as it exists today throughout the world reveals the consequences of speciesism.

On page 117, Singer writes,

Speciesism allows researchers to regard the animals they experiment on as items of equipment, laboratory tools rather than living, suffering creatures.

On pages 136-137, he writes,

The analogy between speciesism and racism applies in practice as well as in theory in the area of experimentation. Blatant speciesism leads to painful experiments on other species, defended on the grounds of their contribution to knowledge and possible usefulness for our species. Blatant racism has led to painful experiments on other races, defended on the grounds of their contribution to knowledge and possible usefulness for the experimenting race. Under the Nazi regime in Germany, nearly two hundred doctors, some of them eminent in the world of medicine, took part in experiments on Jews and Russian and Polish prisoners. Thousands of other physicians knew of these experiments, some of which were the subject of lectures at medical academies. Yet the records show that the doctors sat through verbal reports by doctors on how horrible injuries were inflicted on these “lesser races,” and then proceeded to discuss the medical lessons to be learned from them, without anyone making even a mild protest about the nature of the experiments.

Chapter 6, which begins on page 309, is headed,

Speciesism Today … defenses, rationalizations, and objections to Animal Liberation and the progress made in overcoming them

Singer writes on page 320 that

the overlap between leaders of movements against the oppression of blacks and women, and leaders of movements against cruelty to animals, is extensive; so extensive as to provide an unexpected form of confirmation of the parallel between racism, sexism, and speciesism.

On page 332, he writes,

Speciesism is so pervasive and widespread an attitude that those who attack one or two of its manifestations—like the slaughter of wild animals by hunters, or cruel experimentation, or bullfighting—often participate in other speciesist practices themselves. This allows those attacked to accuse their opponents of inconsistency. “You say we are cruel because we shoot deer,” the hunters say, “but you eat meat. What is the difference, except that you pay someone else to do the killing for you?” “You object to killing animals to clothe ourselves in their skins,” say the furriers, “but you are wearing leather shoes.”

The author does not consider the poor microscopic life that we kill if we, as the more extreme Jains do, gently sweep the ground before us lest we crush life underfoot, breathe through cloth lest we inhale life, filter water lest we drink life to death and so on (see here, here and here, for example).

1983/1986 - ‘Speciesism’ Gains Currency with Regan

1986 saw the publication of A case for animal rights by T. Regan of North Carolina State University at Raleigh in Advances in animal welfare science 1986/87 (pp. 179-189), Washington, DC: The Humane Society of the United States (archive here). A case for animal rights was first published in 1983, according to David Nibert in Animal Rights/Human Rights: Entanglements of Oppression and Liberation (2002). In any case, we will be referring to A case for animal rights as it appears in Advances in animal welfare science in which we read on page 179,

I regard myself as an advocate of animal rights-as part of the animal rights movement. That movement, as I conceive it, is committed to a number of goals, including:

-the total abolition of the use of animals in science;

-the total dissolution of commercial animal agriculture;

-the total elimination of commercial and sport hunting and trapping.

There are, I know, people who profess to believe in animal rights but do not avow these goals. Factory farming, they say, is wrong-it violates animals' rights-but traditional animal agriculture is all right. Toxicity tests of cosmetics on animals violates their rights, but important medical research-cancer research, for example-does not. The clubbing of baby seals is abhorrent, but not the harvesting of adult seals. I used to think I understood this reasoning. Not a11y more. You don't cha.'1ge unjust institutions by tidying them up.

What's wrong-fundamentally wrong-with the way animals are treated isn't the details that vary from case to case. It's the whole system. The forlornness of the veal calf is pathetic, heart wrenching; the pulsing pain of the chimp with electrodes planted deep in her brain is repulsive; the slow, tortuous death of the raccoon caught in the leg-hold trap is agonizing. But what is wrong isn't the pain, isn't the suffering, isn't the deprivation. These compound what's wrong. Sometimes-often-they make it much, much worse. But they are not the fundamental wrong.

The fundamental wrong is the system that allows us to view animals as our resources, here for us-to be eaten, or surgically ·manipulated, or exploited for sport or money. Once we accept this view of animals-as our resources-the rest is as predictable as it is regrettable.

Regan describes on page 184, speciesism as

systematic discrimination based on species membership.

On pages 186-187,

Some there are who resist the idea that animals have inherent value. "Only humans have such value," they profess. How might this narrow view be defended? Shall we say that only humans have the requisite intelligence, or autonomy, or reason? But there are many, many humans who fail to meet these standards and yet are reasonably viewed as having value above and beyond their usefulness to others. Shall we claim that only humans belong to the right species, the species Homo sapiens? But this is blatant speciesism.

1985 ‘Speciesism’ is Added to the Oxford English Dictionary

According to David Nibert in Animal Rights/Human Rights: Entanglements of Oppression and Liberation, published 2002, on pages 7-8,

in 1985, the Oxford English Dictionary defined speciesism as “discrimination against or exploitation of certain animal species by human beings, based on an assumption of mankind’s superiority”

2002 - ‘Speciesism’ Compared to Racism, Sexism & Classism

2002 saw the publication of Animal Rights/Human Rights: Entanglements of Oppression and Liberation by David Nibert who writes on page 10,

speciesism, like racism, sexism, and classism, results from and supports oppressive social arrangements.

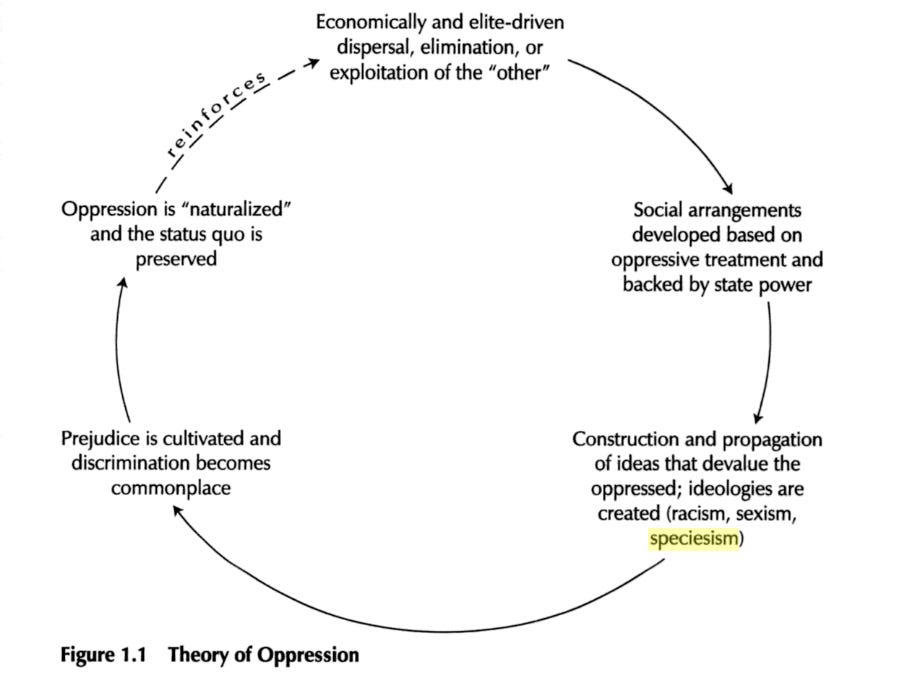

Nibert includes speciesism in his theory of oppression. The following is from page 10.

On page 17, he writes that speciesism

is actually an ideology, a belief system that legitimizes and inspires prejudice and discrimination.

On page 134, Nibert writes,

Capitalism not only drives oppressive practices but also builds ideologies such as speciesism, racism, sexism, and classism that both legitimate oppression and reduce resistance to it

and other wise uses the term speciesism along with the terms racism sexism and classism.

2019 - Matsouka & Sorenson Carry on the Torch

Let’s look at 3 works by A. Matsuoka and J. Sorenson published by Animals and Social Work in June, 2019 insofar as they help us to see how the linguistic currency of the term ‘speciesism’ is being used.

In About Speciesism, A. Matsuoka and J. Sorenson write that after reading and considering Ryder, Regan and Nibert,

we considered speciesism as:

“Within the ideological framework of speciesism and organised according to the needs of capitalism, other animals are considered commodities and resources for our use and their lives are considered expendable as we slaughter them by the billions. Speciesism presents this systemic oppression as natural and acceptable, legitimising and reproducing it” in various cultural, economic and political institutions. (Matsuoka & Sorenson 2014, 71)

In About Critical Animal Studies (2019), they write,

CAS recognizes that various systems of power intersect and that the domination of nonhuman animals operates in the context of other systems of oppression. The oppression of nonhuman animals is justified on the basis of speciesism. The term speciesism was coined in 1970 by Richard Ryder, who characterized it as a form of prejudice that prioritized human interests over those of nonhuman animals. Ryder described this prejudice as being similar to racism and sexism. All of these prejudices are based on morally irrelevant differences, exaggerating them and overlooking similarities in order to disregard the suffering of others. While philosophers Peter Singer and Tom Regan also described speciesism as a prejudice, sociologist David Nibert characterized it as an ideology that serves to legitimize a particular social order. Nibert’s characterization is significant because it emphasizes the fact that speciesism is not simply an individual biased outlook but an institutionalized social practice. This perspective also emphasizes the material interests that underlie exploitation. The ideology of speciesism operates to preserve the privileges of those who benefit most from oppression. Nibert’s work also documented how the oppression of nonhuman animals is consistently entangled with the oppression of various human groups. Thus, speciesism affects not only nonhuman animals but also various groups of humans who are equated with them and, thereby, marginalized. Intersectional understanding of oppression is a critical aspect of CAS. Ecofeminists, like Carol Adams and Josephine Donavan, have made significant contributions to CAS by noting the intersectional oppression of sexism and speciesism not only in individual practices but in institutionalized social practices.

Finally, in About Trans-Species Social Justice,

The ideology of speciesism operates to preserve the privileges of those who benefit most from oppression. The ideology of speciesism normalizes the oppression of nonhuman animals under capitalism as they are viewed as commodities and resources for human use. As you can see from our definition, we consider speciesism is not only a prejudice but an ideology which supports institutional conditions.

What are your thoughts on this matter?

SOURCES

Matsuoka, A. & Sorenson, J. - About Speciesism - Animals and Social Work (June, 2019)

Matsuoka, A. & Sorenson, J. - About Trans-Species Social Justice - Animals and Social Work (June, 2019)

Matsuoka, A. & Sorenson, J. - What is Critical Animal Studies? - Animals and Social Work (June, 2019)

Nibert, David - Animal Rights/Human Rights: Entanglements of Oppression and Liberation - Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. (2002)

Regan, T. - A case for animal rights (1986) - Advances in animal welfare science 1986/87 (pp. 179-189). Washington, DC: The Humane Society of the United States. (archive here)

Singer, Peter - Animal Liberation - Open Road (1975, reprint 2015)

See the following resources and sources;

European Association for Critical Animal Studies

ICAS - Institute for Critical Animal Studies

North American Association for Critical Animal Studies

Critical Animal Studies - Thinking the Unthinkable by John Sorenson

Critical Animal Studies and Social Justice - Critical Theory, Dismantling Speciesism, and Total Liberation edited by Anthony J. Nocella II and Amber E. George

Critical Animal Studies - Towards Trans-species Social Justice edited by Atsuko Matsuoka & John Sorenson

Critical Animal Studies edited by Richard Twine & Claire Parkinson

Defining Critical Animal Studies - An Intersectional Social Justice Approach for Liberation by Anthony edited by J. Nocella II, John Sorenson, Kim Socha & Atsuko Matsuoka

Journal of Critical Animal Studies

Rise of Critical Animal Studies - From the Margins to the Centre edited by Nik Taylor & Richard Twine

Culture War Encyclopedia - others claim & move on, we prove & archive forever.

∴ Liberty ∴ Strength ∴ Honor ∴ Justice ∴ Truth ∴ Love ∴ Laughter ∴

See the Culture War Encyclopedia on

∴ Veritas uniat divisos ∴