updated Nov 12, 2024

CONTENTS

Video Version of This Section of the CWE

Karl Marx was Racist

Marxism is Totalitarian

Dictatorship

Dictatorship in the Communist Manifesto

More From Marx on the Dictatorship

More From Engels on the Dictatorship

Insight into Marx’s Character

Moron MarxMore on Marx

UNDER CONTRUCTION

Below is a video covering the first section below.

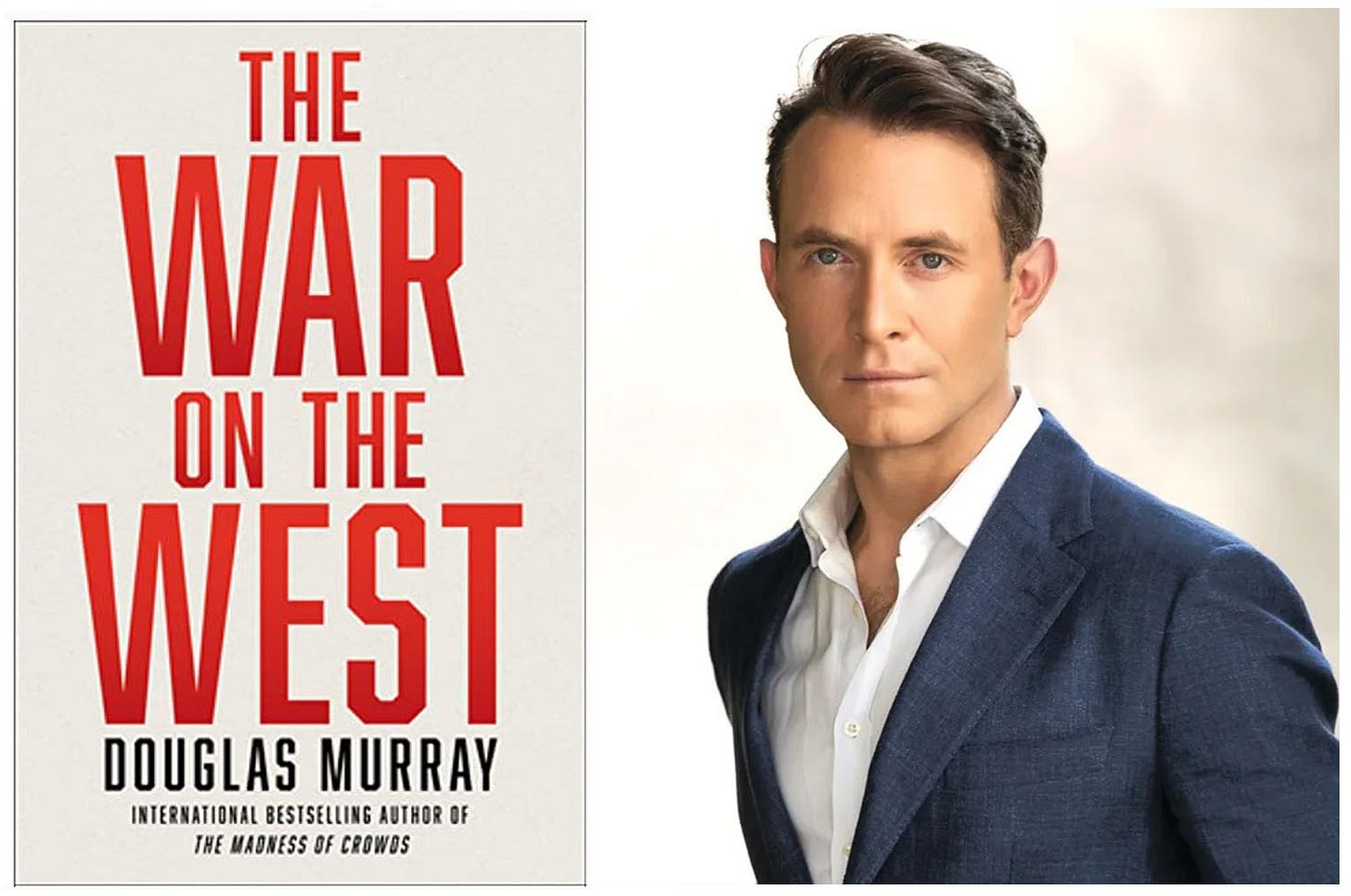

“One of the pleasures in recent years has been watching people who think thy are being a good liberal boundary keeper discover that one of their feet has nicked one of the tripwires.”

- Douglas Murray in The Madness of Crowds - Gender, Race and Identity (2019, page 241)

Sorry, Marxists, socialists and communists, you’re racist. You see, Karl Marx was racist so Marxism/socialism/communism is racist too, right? Also, you’re a totalitarian - just like a Nazis and fascists - because, as we’ll see, Marx called for a dictatorship. But first, the racism…

In his book The War on the West (2022), Douglas Murray discusses many examples of the destruction of public monuments and statues in the West in recent years. Some were once iconic but became historic relics as society changed its position on things like the treatment of American Indians and slavery. Some remained iconic, being that they did not represent such injustices, but were destroyed just the same. I provide what Murray writes about these examples under iconoclasm in the Culture War Encyclopedia.

Murray also points out some hypocritical inconsistencies in all this. For you see, icons for the left such as Michel Foucault and Karl Marx are excused for their bigotry because, well, they are icons for the left.

On pages 174-181 of The War on the West, Murray writes,

WHY DO THEIR GODS NOT FALL?

Yet there are many oddities in all of this. Kant, Hume, Jefferson, Mill, Voltaire, and everyone else connected to racism, empire, or slavery must fall. And yet a strange selection of historical figures does not. And in this fact, we get to the roots of something that is happening in the anti-Western moment.

The Highgate in London, one of the largest monuments in the cemetery is a great bust on top of a huge stone pillar. On the front are quotes from The Communist Manifesto ("Workers of the all lands unite") and from the Thesis on Feuerbach ("The philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways. The point however is to change it"). The man whose tomb this is - is of course Karl Marx. To this day, it remains a place of pilgrimage for people who think that Marx changed the world in a good way. All have their own spin for dealing with the fact of the roughly one hundred million people who were killed in trying to change the world along Marx's lines.

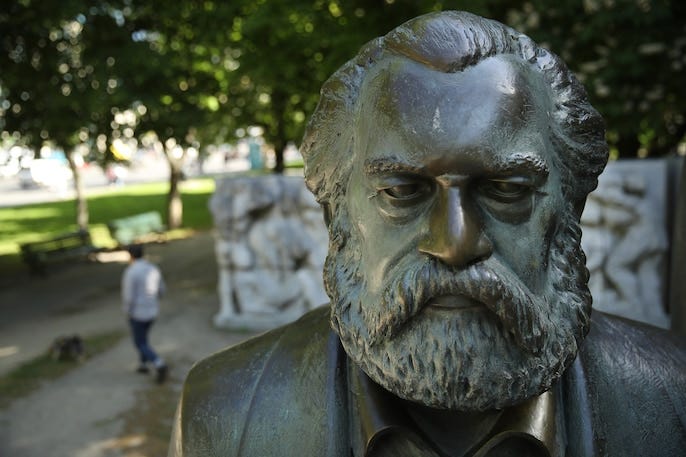

Yet it stands there still, and there have been no serious efforts to topple it or destroy the bust. Occasionally it has been daubed in red paint - with such vandalism always condemned by cultural and political figures alike. But through the events of recent years, there have been no online petitions or crowd efforts to pull it down or kick it into a nearby river. There may be reasons for that, of course, which is that it is a tombstone, and even the most doctrinaire people might find it distasteful to desecrate a grave. Yet the monument in Highgate is not the only memorial to Marx or Marxism that stands. As recent as 2016, Stalford University unveiled a new memorial on its campus. the huge bust of Freidrich Engels - coauthor of The Communist Manifesto - was made into a feature of campus life. In part to commemorate the fact that Marx and Engels used to drink in a nearby pub when they lived in the area in the 1840s. The university authorities paid for the vast five-meter-tall sculpture as a tribute to the two men.

As recently as 2018, on the two hundredth anniversary of his birth, a vast new larger-than-life statue of Marx was unveiled in the town of Trier in the southwest of Germany, just near the borders with Luxembourg, Belgium, and France. The fourteen-foot-tall bronze statue was donated by the authorities in China, and the hundreds of guests at the unveiling included a delegation from the Chinese Communist Party. It seems as though a connection with Marx or Marxism is no ethical problem, perhaps even a plus. In April 2021, when students at the University of Liverpool forced the university authorities to rename a building named after the nineteenth-century prime minister William Gladstone (because of his father's links with slavery), they renamed the hall after a civil rights campaigner and lifelong Communist Party member called Dorothy Kuya.

I found a photo of the statue and others…

There is no special effort to eradicate, problematize, decolonize, or otherwise act in an "antiracist" manner against the legacy of Karl Marx and his circle. And this is strange because as anybody who has read the work of Marx will know - especially anyone who has read his letters with Engels - Marx's reputation by the lights of our own age ought to be toast by now.

Consider the racism in Marx's letters to Engels, where the two great communists converse privately about the issues of their day: Here is a letter from Marx to Engels written July 1862:

“The Jewish nigger Lassalle who, I'm glad to say, is leaving at the end of this week, has happily lost another 5,000 talers in an ill-judged speculation . . . It is now quite plain to me - as the shape of his head and the way his hair grows also testify - that he is descended from the negroes who accompanied Moses' flight from Egypt (unless his mother or paternal grandmother interbred with a nigger). Now, this blend of Jewishness and Germanness, on the one hand, and basic negroid stock, on the other, must inevitably give rise to peculiar product. The fellow's importunity is also nigger-like.”1

Of course, this is not a nice way to speak about anybody. But a charitable interpretations, such as has been denied to David Hume, might say that this is just one ugly thing said by Marx in a private letter and that we shouldn't judge him harshly on it. yet this is not the only occasion that such a sentiment came from Marx's pen. Here is another letter to Engels, written four years later (in 1866), in which Marx describes a recent work he believes Engels might benefit from. By this stage, both men are aware of the discoveries of Charles Darwin, whose work on the origins of the species, natural selection, and much more were of course unavailable to the philosophers of the Enlightenment. Marx is interested in Pierre Tremaux and his Origine et transformations de l'homme et des autres etres (Paris 1865). By now the monogenesis argument (that is, that human beings are all related and are not different species) was winning the intellectual war, Frederick Douglass and others had made highly persuasive, and ultimately successful, interventions into the debate. And yet even now still Marx is playing around with the polygenisis argument. As he tells Engels of Tremaux's work: "In spite of all the shortcomings that I have noted, it represents a very significant advance over Darwin. . . . E.g., . . . (he spent a long time in Africa) he shows that the common negro type is only a degeneration of a far higher one."2

Perhaps this was just a blind spot for Marx? Perhaps he had a problem with black people but not with other groups?

Here is Marx in another letter to Engels, where he manages to get onto the subject of Jews: "The expulsion of a Leper people from Egypt, at the head of whom was an Egyptian priest named Moses. Lazarus, the leper, is also the basic type of Jew."3

Of course, there is another way in which this also could be defended. It might be said that Marx was not writing for public consumption in these letters. His reflections on the "degenerative" nature of the "common negro" and the "leprous" nature of the Jewish people are ugly, certainly, but they are private reflections in a private letter written privately to a friend. Like the letter that Thomas Jefferson sent to the Marquis de Chastellux. But the problem with Marx is that he didn't just keep his racism to his private reflections in a private letter written privately to a friend. Like the letter that Thomas Jefferson sent to the Marquis de Chastellux. But the problem with Marx is that he didn't just keep his racism to his private correspondence with his coauthor on The Communist Manifesto.

In 1853, in one of his pieces for the New York Tribune, Marx wrote of the Balkans that it had "the misfortune to be inhabited by a conglomerate of different races and nationalities, of which it is hard to say which is the least fit for progress and civilization,"4

In 1856, he could be found writing in the same paper that "we find every tyrant backed by a Jew" and claiming that there exists always "a handful of Jews to ransack pockets." Starting from the time of Jesus and the throwing of the moneylenders out of the Temple, Marx tells his audience that "the loan-mongering Jews are so strong that it is timely and expedient to expose and stigmatize their organization."5

And these proto-Hitlerian views are not from a single period of Marx's life. Rather, they are consistent throughout it. Over a decade earlier, in 1843, Marx writes in "On the Jewish Question": "What is the worldly religion of the Jew? Huckstering. What is his worldly God? Money. . . . Money is the jealous god of Israel, in face of which no other god may exist."6

Well, you might say, perhaps Marx simply didn't like Jews very much? Except that he didn't seem to like other races very much either and had just as little respect for their great histories as he did for the history of the Jews. In 1853, he is telling his audience in America, "Indian society has no history at all, at least no known history." And while Marx is simultaneously damning and utterly ignorant of Indian civilization, he does seem to favor British rule of India. "The question," he says, "is not whether the English had a right to conquer India, but whether we are to prefer India conquered by the Turk, by the Persian, by the Russia, to India conquered by the Briton." One role of Britain in India, Marx asserts, is to lay "the material foundations of Western society in Asia." He is inclined to think that they can do it,. For although Marx notes that other civilizations had overrun India, these earlier "barbarian conquerors" had been unequal to the task. Whereas "the British were the first conquerors superior, and therefore, inaccessible to Hindoo civilization."7

Still, Marx may have been antiblack, anti-Semitic, anti-Indian, procolonialist, and racist both in public and in private. But at least he cannot be connected with the other great sin of the West. Alas, as though proving to posterity that Marx could get every issue wrong here he is writing about Slavery in 1847, ahead of the American Civil War and already very much on the wrong side of that conflict: "Slavery is an economic category like any other."

Marx weighed up the bad side and what he called "the good side of slavery." And he found a lot of good to say about it: "Without slavery North America, the most progressive of countries, would be transformed into a patriarchal country. Wipe North America off the map of the world, and you will have anarchy - the complete decay of modern commerce and civilization. Cause slavery to disappear and you will have wiped America off the map of nations."8

Why is it worth reeling off this incomplete list of what are - in our own era - an almost clean sweep of offences? Not simply because they demonstrate that the most significant figure in the history of left-wing thought, indeed its genesis figure and prophet, perhaps even its god, was guilty of every one of the vices levelled at all non-Marxists in the West. But in any analysis, Marx was far worse than any of the people who largely leftist campaigners have spent recent years lambasting . Marx's anti-Semitism is more noxious than Immanuel Kant's. His career-long record of racism makes a single foot-note in the work of David Hume look very slight. His language of superior and inferior races was of a kind that progressive thinkers such as John Stuart Mill already abhorred and worse than anything Thomas Jefferson engaged in.

The only defence that might be made of him by his defenders and disciples is that he was a man of his time. That Marx lived in the nineteenth century and therefore held on to a number of the era's more unpleasant attributes. And yet this defence is packed with explosives waiting to go off in the face of anyone hoping to use them. First, because who is not a man of their own time? Every person whose reputation has been brought down in the cultural revolution of recent years was also a man or woman of his or her own time. So why should this excuse be successful when used in defence of Marx, yet dismissed when used in defence of Voltaire or Locke? With Marx, there is another problem in his defence, which is that for his defenders, he is not simply another thinker. He is not even to be compared with Hume or the sage of Konigsberg. For his followers, Marx is the last or (depending on how you count it) the originating prophet. He was not just a thinker or a sage - he was the formulator of a world revolutionary movement. A movement that claimed to know how to reorder absolutely everything in human affairs in order to arrive at a utopian society. A utopian society that has never been achieved and has cost many millions of lives in not being achieved but that activists across the West still dream of instituting next time: always next time.

It may be said that a prophet should be held to a higher standard than a mere philosopher, antiquarian, or botanist. A 2019 biography of Marx was reviewed in the New York Times under the headline "Karl Marx: Prophet of the Present." The paper's reviewer (while noting in passing some of Marx's less seemly comments about Jews) concluded that the work "makes the case for taking Marx seriously today as a pragmatic realist, as well as a messianic visionary" who "never lost his belief in a redemptive future."9

Which is a beautiful idea, of course. And entirely divorced not just from every detail of the consequences but from the reality of the man in question.

What becomes clear in analyzing the differences between the treatment of Marx and the treatment of almost every other thinker of the West is that the game is worse than inconsistent. It exists to cut a swath through every thinker or historical figure in the Western tradition. To lambaste them for holding on to one or more of the attitudes of their time that our own age holds o be abhorrent. And at the same time to ensure that figures whose work is helpful in pulling apart the Western tradition, even to the point of demanding revolution to overturn it, are never treated to this same ahistorical and retributive game. Marx is protected because his writings and reputation are useful for anyone wishing to pull down the West. Everybody else is subjected to the process of destruction because their reputations are useful for holding up the West. After all, remove every other philosopher from the field, take down all their monuments and the tributes to them, and ensure that their thought is taught primarily (and ahistorically) as a story of racism and slavery and what is left standing in the Western tradition?

For anyone who doubts that this is the game that is being engaged in, perhaps one other example may suffice.

He then goes on to explain that the left’s beloved academic Michel Foucault apparently raped marginalized people, that is, darker, foreign children who were desperately poor, poor enough to meet him in a graveyard at night for money, a graveyard where he then raped them. Murray then notes that,

nowhere has there been any recantation by his disciples in disciplines across America or anywhere else because of the revelations of racially motivated child rape.

After discussing Foucault, Douglas Murray continues (pages 182-183),

Like the double standard over Marx's racism, this fact is suggestive. For it would surely be different if it had worked the other way around. If one of the twentieth century's great conservative thinkers had been revealed to have travelled to the developing world in order to rape young boys on a tombstone in a graveyard at night, it might be considered suggestive. The political left would likely be unwilling to let it slide by completely. Nor would they be willing to pass up the opportunity to extrapolate some extra lessons. They might say that this habit was revealing of a wider conservative mindset. That it revealed pedophilic, rapist, racist tendencies at the heart of Western thought. They might even try to point out that a whole cultural movement or societal tendency was tarred by association with this nocturnal and noxious habit. But with Foucault, no such thing has happened. He remains on his throne. His work continues to spill out. And nobody to date seems to think there is anything especially telling about one of the founding icons of the anti-Westernism of our time having found personal pleasure in purchasing native children of foreign countries to satisfy his sexual desires.

It is in such omissions and double standards that something crucial can be discerned. Which is that what is happening in the current cultural moment is not simply an assertion of a new moral vision but the attempted imposition of a political vision on the West. One in which only specific figures – whom the West had felt proud of – are brought low, the only figures who will still remain on their pedestals (both real and metaphorical) are those figures who were most critical of the West. Meaning that the only people left to guide us would be the people who will guide us in the worst possible directions.

See my upcoming entry on Michel Foucault in the Culture War Encyclopedia for more about that, so be sure to subscribe. Also, please share this.

Marxism is Totalitarian

All bold has been rendered by the present editor.

Dictatorship

The Marxists at marxists.org write in their glossary under dictatorship that

Right into the nineteenth century, ‘dictatorship’ was used in the sense of the management of power in a state of emergency, outside of the norms of legality, sometimes, but not always, implying one-man rule, and sometimes in reference to the dominance of an elected government over traditional figures of authority.

The French Revolution was frequently referred to by friends and foes alike as a dictatorship. Babeuf’s “Conspiracy of Equals” advocated a dictatorship exercised by a group of revolutionaries, having the task of defending the revolution against the reactionary peasants, and educating the masses up to the eventual level of a democracy, a transitional period of presumably many decades. It was this notion of ‘dictatorship’ that was in the minds of Auguste Blanqui and his followers who actively advocated communist ideas in the 1830s and ’40s.

Hopefully it does not need to be explained that the USA is not a democracy but rather a constitutional republic. The Marxists at marxists.org also write,

Modern usage of the term begins to appear in connection with the Revolutions which swept Europe in 1848. The Left, including its most moderate elements, talked of a dictatorship, by which they meant nothing more than imposing the will of an majority-elected government over a minority of counter-revolutionaries. Terrified by the uprising of the Parisian workers in June 1848, the Provisional Government handed over absolute power to the dictatorship of General Cavaignac, who used his powers to massacre the workers of Paris. Subsequently, a state-of-siege provision was inserted into the French Constitution to provide for such exigencies, and this law became the model for other nations who wrote such emergency provisions into their constitutions. From the middle of the nineteenth century, the word ‘dictatorship’ was associated with this institution, still more or less faithful to the original Roman meaning — an extra-legal institution for the defence of the constitution.

It was only gradually, during the 1880s, that ‘dictatorship’ came to be routinely used to mean a form of government in contrast to ‘democracy’ and by the 1890s was generally used in that way. Prior to that time, throughout the life-time of Karl Marx for example, it was never associated with any particular form of government, everyone understanding that popular suffrage was as much an instrument of dictatorship as martial law.

Dictatorship in the Communist Manifesto

In the Manifesto of the Communist Party by Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, published in 1848, under Chapter II Proletarians and Communists, we read,

The immediate aim of the Communist is the same as that of all the other proletarian parties: formation of the proletariat into a class, overthrow of the bourgeois supremacy, conquest of political power by the proletariat.

Further on in this chapter, we read,

The Communists are further reproached with desiring to abolish countries and nationality.

The working men have no country. We cannot take from them what they have not got. Since the proletariat must first of all acquire political supremacy, must rise to be the leading class of the nation, must constitute itself the nation, it is, so far, itself national, though not in the bourgeois sense of the word.

National differences and antagonisms between peoples are daily more and more vanishing, owing to the development of the bourgeoisie, to freedom of commerce, to the world-market, to uniformity in the mode of production and in the conditions of life corresponding thereto.

The supremacy of the proletariat will cause them to vanish still faster.

Also…

The proletariat will use its political supremacy to wrest, by degrees, all capital from the bourgeoisie, to centralise all instruments of production in the hands of the State, i.e., of the proletariat organised as the ruling class; and to increase the total of productive forces as rapidly as possible.

Furthermore, Marx and Engels wrote in this section,

Political power, properly so called, is merely the organised power of one class for oppressing another. If the proletariat during its contest with the bourgeoisie is compelled, by the force of circumstances, to organise itself as a class, if, by means of a revolution, it makes itself the ruling class, and, as such, sweeps away by force the old conditions of production, then it will, along with these conditions, have swept away the conditions for the existence of class antagonisms and of classes generally, and will thereby have abolished its own supremacy as a class.

In place of the old bourgeois society, with its classes and class antagonisms, we shall have an association, in which the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all.

You see, according to Marxist theory, dictatorships will give up their power along with their property and everything else. Marx would write years later, in Critique of the Gotha Programme (1875) in section IV,

Between capitalist and communist society there lies the period of the revolutionary transformation of the one into the other. Corresponding to this is also a political transition period in which the state can be nothing but the revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat.

Indeed, Marxists may argue that this dictatorship is only temporary, displaying either a lack of experience with people who wield power and their reluctance to relinquish that power of hypocrisy. As Britannica states,

Contrary to Marx’s vision and as George Orwell (1903–50), Mikhail Bakunin (1814–76), and others had foreseen, the proposed dictatorship of the proletariat eventually became a dictatorship of former proletarians.

More From Marx on the Dictatorship

According to, for example, marxists.org, in a letter to J. Weydemeyer in 1852, Marx wrote that

class struggle necessarily leads to the dictatorship of the proletariat

Some more context is needed here to be fair. You see, Marx then wrote that

this dictatorship itself only constitutes the transition to the abolition of all classes and to a classless society.

But, to be fair, we must also point out how no such dictatorship after a Marxist/socialist/communist revolution has ever been a transition to a classless society. Also, does anyone really believe that a dictatorship would voluntarily give up power?

The website for marxists.org hosts Works of Karl Marx 1850 - The Class Struggles in France, 1848 to 1850 in which Marx argues that “utopian doctrinaire socialism” unrealistically “does away with the revolutionary struggle of the classes” and “at bottom only idealizes present society”.

He furthermore argues that “the proletariat rallies more and more around revolutionary socialism, around communism,” and that this “revolutionary socialism” includes “the permanence of the revolution”. How can a revolution be permanent?

Marx writes that “the class dictatorship of the proletariat” is “necessary”. But then again, he does seem to be arguing that this “dictatorship” would be transitional. He writes that revolutionary socialism, the socialism of the workers, the proletariat, involves,

the permanence of the revolution, the class dictatorship of the proletariat as the necessary transit point to the abolition of class distinctions generally,

Notice how the idea of this “necessary” dictatorship of the “proletariat” (who, in practice, would perhaps not exactly be proletariat people (workers) but who instead might be (ex-)college students/activists/politicians) is juxtaposed with the idea of permanence and yet it is supposed to be transitional but it would be in transit to a classless world, a world that may be unobtainable and that could therefore be said to be nowhen or nowhere. Utopia means “nowhere” for a reason. If this utopian classless world could never be realized, the dictatorship would be permanent.

Also, let’s face it, in reality, would any dictatorship give up power? Would power need to be wrested from it? If so, would that be a counter-revolution? Would it be just a new revolution of the merry-go-round?

Recall the moral behind the warning against the temptation of the dark side of the Force in the Star Wars universe, the warning against the temptation of power in the symbol of the One Ring to rule them all and in the darkness bind them, the warning in the story of the Devil tempting Jesus with ultimate worldly power, political power. Who among us would have the personal power to not become addicted to ultimate political power? The answer is certainly not those who would seek such power in the first place. We can safely bet that anyone who seeks such power wants that power and would not want to give it up, even for a Worker’s Utopia.

Isn’t ‘Worker’s Utopia’ an oxymoron anyway?

At any rate, you should not trust us that we did not take anything out of context or misrepresent. Here’s everything we quoted above is from the following passage (again, all bold rendering is from the present editor),

While this utopian doctrinaire socialism, which subordinates the total movement to one of its stages, which puts in place of common social production the brainwork of individual pedants and, above all, in fantasy does away with the revolutionary struggle of the classes and its requirements by small conjurers' tricks or great sentimentality, while this doctrinaire socialism, which at bottom only idealizes present society, takes a picture of it without shadows, and wants to achieve its ideal athwart the realities of present society; while the proletariat surrenders this socialism to the petty bourgeoisie; while the struggle of the different socialist leaders among themselves sets forth each of the so-called systems as a pretentious adherence to one of the transit points of the social revolution as against another – the proletariat rallies more and more around revolutionary socialism, around communism, for which the bourgeoisie has itself invented the name of Blanqui. This socialism is the declaration of the permanence of the revolution, the class dictatorship of the proletariat as the necessary transit point to the abolition of class distinctions generally, to the abolition of all the relations of production on which they rest, to the abolition of all the social relations that correspond to these relations of production, to the revolutionizing of all the ideas that result from these social relations.

The scope of this exposition does not permit of developing the subject further.

More From Engels on the Dictatorship

According to marxists.org, Engel’s The Housing Question was first published across a number of issues of Der Volksstaat from 1872 to 1873 and in this, Engels writes that the concept of

the dictatorship of the proletariat as the transitional stage to the abolition of classes and with them of the state

had

already been expressed in The Communist Manifesto and since then on innumerable occasions.

According to marxists.org in 1891, Engels wrote A Critique of the Draft Social-Democratic Program of 1891 and in this, Engels uses

the Great French Revolution

as an example of

the dictatorship of the proletariat.

In Engels to Conrad Schmidt In Berlin (1890), according to marxists.org, Engels writes,

Or why do we fight for the political dictatorship of the proletariat if political power is economically impotent? Force (that is state power) is also an economic power.

In Engels to Conrad Schmidt In Berlin (1890), Engels wrote, according to marxists.org,

Or else, why are we struggling for the political dictatorship of the proletariat, if political power has no economic effects? Force (i.e., the state power) is also an economic power!

Insight into Marx’s Character

There is a letter, they say, from Karl Marx’s father Heinrich Marx to Karl Marx that seems to give us some insight into Karl’s character. One may know from experience that fathers tend to not revel in pointing out serious flaws in their sons and that it is only out of tough love that fathers engage in the activity. This is not an absolute rule, of course. Some fathers may actually enjoy putting their sons down. But that seems to be an aberration, not the usual case. At any rate, even according to Marxists themselves, the following is a letter written to Karl from his father Heinrich and sister Sophie.

Dear Karl,

Have you still your headquarters in Stralow? At this time of year and in the land where no lemon trees are in bloom, can this be thinkable? But where are you then? That is the question, and for a practical man the first requirement for correspondence is to know an address. Therefore, I have to take advantage of the kindness of others.

An address, however, is form, and precisely that seems to be your weak side. Things may well be different as regards material? At least, one should suppose so, if one bears in mind: 1) that you have no lack of subject-matter, 2) that your situation is serious enough to arouse great interest, 3) that your father is perhaps somewhat partial in his attachment to you, etc., etc., etc., and yet after an interval of two months, the second of which caused me some unpleasant hours full of anxiety, I received a letter without form or content, a torn fragment saying nothing, which stood in no relation to what went before it and had no connection with the future!

If a correspondence is to be of interest and value, it must have consistency, and the writer must necessarily have his last letter before his eyes, as also the last reply. Your last letter but one contained much that excited my expectation. I had written a number of letters which asked for information on my points. And instead of all that, I received a letter of bits and fragments, and, what is much worse, an embittered letter.

Frankly speaking, my dear Karl, I do not like this modern word, which all weaklings use to cloak their feelings when they quarrel with the world because they do not possess, without labour or trouble, well-furnished palaces with vast sums of money and elegant carriages. This embitterment disgusts me and you are the last person from whom I would expect it. What grounds can you have for it? Has not everything smiled on you ever since your cradle? Has not nature endowed you with magnificent talents? Have not your parents lavished affection on you? Have you ever up to now been unable to satisfy your reasonable wishes? And have you not carried away in the most incomprehensible fashion the heart of a girl whom thousands envy you? Yet the first untoward event, the first disappointed wish, evokes embitterment! Is that strength? Is that a manly character?

You yourself had declared, in dry words, that you would be satisfied with assurances for the future, and because of them renounce all outward signs for the present. Did you not make that renunciation word for word in writing? And only children complain about the word they have given when they begin to feel pressure.

Yet here too your luck holds. Your good mother, who has a softer heart than I have and to whom it still very often occurs that we too were once the plaything of the little blind rogue, sounded the alarm, and the all too good parents of your Jenny could hardly wait for the moment when the poor, wounded heart would be consoled, and the recipe is undoubtedly already in your hands, if a defective address has not caused the epistle to go astray.

Time is limited, for Sophie is to take the letter before the post to the von Westphalens, who now live far away, and this good opportunity also was announced to me only today, so that I must conclude. As a matter of fact, at present I would not know what to say, at most I could only put questions to you, and I do not like to be importunate. Only one thing more my Herr Son will still allow me, namely, to express my surprise that I have still not received any request for money! Or do you perhaps want already now to make up for it from the too great amount taken? It's a little too early for that.

Your dear mother refused to reconcile herself entirely to the fact that you did not come home in the autumn as the others did. If it is too long for you and dear mother until next autumn, you could come for the Easter vacation.

Your faithful father

Marx

[Postscript by Marx's sister Sophie]

Good-bye, dear Karl, let us have news soon that you are now satisfied and that your mind is at rest. Until Easter, Karl, the hours until then will seem to me an eternity!

To some of us, we may recognize in this letter the sort of relationship we have witnessed in our own lives. Perhaps we are reminded of an entitled sibling or a difficult daughter, for example. One may also be reminded of the character of any person in our lives who is a socialist of some kind, an antifa supporter, BLM supporter or just an entitled, ungrateful, selfish, bitter, loveless, lazy asshole.

Moron Marx More on Marx

Milton Friedman totally destroys a Marxist by Simply Explained (June 20, 2017)

Karl Marx Didn't Understand Human Nature And Communism is a Lie by Styxhexenhammer666 (May 7, 2018)

Jordan Peterson's Critique of the Communist Manifesto by Jordan B Peterson (April 17, 2021)

Why I quit being a Marxist | Thomas Sowell by Thomas SowellTV (August 2, 2022)

Jordan Peterson and Paul Kengor - Marx's Early Work Explains a Lot by Liberty Vault (August 9, 2024)

Thanks,

Justin Trouble

Laughter my Shield, Knowledge my Steed

Wit I may Wield, but Question my Rede

Liberty my Right, Truth my Sword

Love my Life, Honor my Reward

This is part of the Culture War Encyclopedia.

F O O T N O T E S

Murray’s footnote 29: Karl Marx to Friedrich Engels, July 30, 1862, Marx and Engels Collected Works, vol. 41 (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1984), p. 388.

Murray’s footnote 30: Marx to Engels, August 7, 1866, Marx and Engels Collected Works, vol. 42, 303.

Murray’s footnote 31: Marx to Engels, May 10, 1861, Marx and Engels Collected Works, vol. 41, p.283

Murray’s footnote 32: Karl Marx, “The Russian Menace to Europe,” New York Tribune, April 7, 1853.

Murray’s footnote 33: Karl Marx, “The Russian Loan,” New York Tribune, January 4, 1856.

Murray’s footnote 34: Karl Marx, “On the Jewish Question” (1843), in Karl Marx: Selected Writings, 2nd ed., ed. David McLellan (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000, pp. 66-69.

Murray’s footnote 35: Karl Marx, “The Future Results of British Rule in India,” NewYork Daily Tribune, August 8, 1853.

Murray’s footnote 36: Karl Marx, The Poverty of Philosophy (1847) (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1955), pp. 49-50.

Murray’s footnote 37: James Miller, “Kark Marx: Prophet of the Present,” New York Times, August , 2019.