This is part of the Culture War Encyclopedia.

∴ Donate to us, please. ∴

Now with a forward by Tarl Warwick, AKA Styxhexenhammer666.

Updated March 4, 2024. Under construction, please be patient.

C O N T E N T S

FORWARD by Tarl Warwick, AKA Styxhexenhammer666

INTRODUCTION

OVERVIEW of CRITICAL RACE THEORY ACCORDING to CRITICAL RACE THEORISTS

Short Version

Overview of CRT According to Cornel West

Overview of CRT According to John Calmore

Overview of CRT According to Other Critical Race Theorists

HISTORY of CRT

Postmodernism Paves the Way for CRT

A Brief Background in Postmodernism

Beginning of CRT & the Coining of the Term

From Radical Feminism & Critical Legal Studies to CRT

CRT’s Marxism

CRT’s Anti-Liberal Past & Present

Alternative Course

Foundational CRT

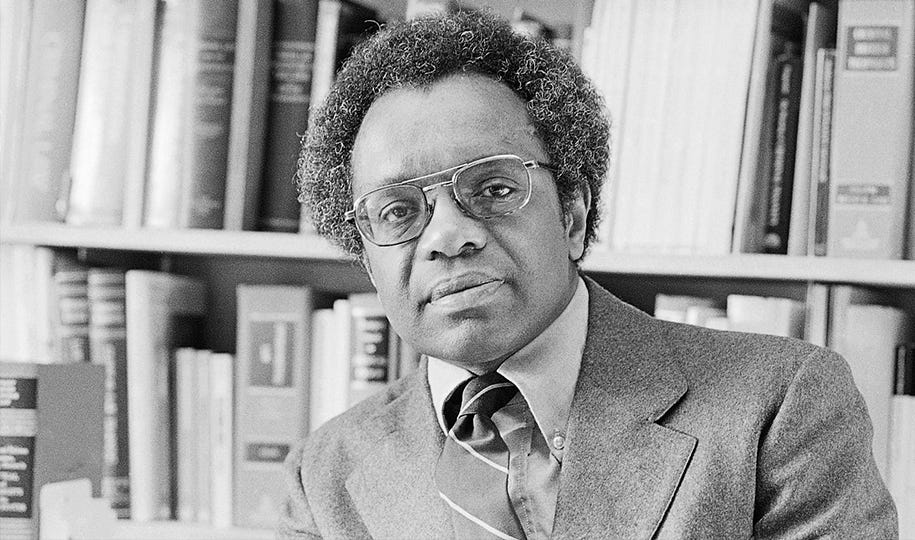

Derrick Bell & Criticism of Racial Desegregation

Alan Freeman & Criticism of Racial Desegregation

Derrick Bell & Interest Convergence

Richard Delgado & Unconscious Racism

SUMMARY of CRT’s FOUNDATION - CRT Opposes Race Neutrality & Civil Rights

CRT in the 1990s

CRT TODAY

Spread of CRT

Class & Race in CRT

MAJOR COMPONENTS of CRT

WHAT CRT WANTS

Affirmative Action

Black Nationalism, White Nationalism, etc.

Black Rage

Critical White Studies

Cumulative Voting

Identity Politics

Identity

Non-Neutrality

Oppositional Scholarship

Race Consciousness

Racial Realism

Racial Separatism

Reparations

WHAT CRT OPPOSSES

Color Blindness

Free Speech

Liberalism

Merit

Race Neutrality

Racial Assimilation

Racial Integration

Rights

OTHER CONCERNS & ASPECTS of CRT

Essentialism

Hate Crimes

Hate Speech

Implicit Bias

Interest Convergence

Intersectionality

Material Determinism

Matrix of Domination

Microaggressions

Race, Social Construction

Revisionist History

Revisionist Interpretation

Social Dominance Theory

Structural Determinism

Unconscious Racism

Voice of Color Thesis

White Privilege

Whiteness as Property

CRITICISM of CRT

Carl Benjamin

Douglas Murray

Tarl Warwick (Styxhexenhammer666)

Justin Trouble

Critical Race Theory in Schools

Are They Teaching CRT in Schools?

Are They Just Teaching History?

CRT TOMORROW

CRT’s OFFSPRING

Asian American Critical Race Studies (AsianCrit)

American Critical Race Studies (TribalCrit)

Critical Race Feminism (CRF)

Critical Race Masculinism (CRM)

Critical White Studies (CWS)

Latino Critical Race Studies (LatCrit)

APPENDIX: About the Crits Referenced in This Piece

Bibliography

Further Sources

Also see the following sections in the Culture War Encyclopedia

Footnotes

FORWARD by TARL WARWICK, aka STYXHEXENHAMMER666

The following forward was graciously provided by its author at the request of we, the staff here at the Culture War Encyclopedia (Justin Trouble and Tabby), who greatly appreciate it. It seems that brevity is indeed the soul of wit. For, you see, his forward below encapsulates with profundity and succinctness that which is most important to know about CRT in a way that I, Justin Trouble, whose eyes have become too accustomed to looking at it through a microscope was unable to. We are honored.

FORWARD

Critical Race Theory (often given the simplistic acronym “CRT”) is an interesting subject- not so much because of its own internal rigor (for it contains little), but because of public reaction to the same. The subject is relatively easily understood, but is debated fairly hotly nonetheless- a sure sign of social propaganda being utilized. The premise of the “theory” (really more a catch-all Marxist dog-whistle) can be debunked in many ways- Fairly simply, as in my own treatment of the concept, or much more thoroughly, as in the present work, with quotations, notes, and so forth.

CRT is effectively a self refuting overall schema of thought in the social and political sense. It posits a legal system built by and for white people, while seeking to increase the scope and power of the same system, with the supposed goal of uplifting people who are not white. How this can happen in such a professedly corrupted system is scantly addressed. It proposes (in some literature) that the civil rights era in the United States was fundamentally a failure, and that it is reparations (economic vengeance) that will solve long-standing ethnic and racial issues, not the concept of equality under the law.

The profuse terminology subjugate to the premise itself at times approaches a level of convolution reserved more generally for “the bad guys” in a dystopian fiction novel. “Microaggression” is the mere shining tip of a gigantic iceberg languishing in darker waters below. In this work- which I have read with great delight- you will see things far more bizarre and intellectually decrepit than just the now already-outdated microaggression. Indeed, what was labeled hilariously “out there” a half decade ago is now normal parlance, and with each sharpening of the knife of propaganda and pseudoscience, a new edge is born.

Where my own work on this subject was effectively meant as a brief primer based on the premises of CRT proposed by its adherents and supporters, this work here is more of an exhaustive effort, as I previously stated, providing quotations and so forth. It is intriguing that people seriously employed, sometimes in positions of power, have adopted an un-critical view of this supposedly critical theory (or system of sub-theories) and that it is being actively promulgated in educational, political, and legal circles. We may comfort ourselves by thinking that only a fool would believe in a concept such as CRT- as it is, again, self refuting and ignores a competent view of Western history- but this is perhaps unhelpful; in the end either a significant number of our fellow citizens are therefore fools (believing in the same) or are rather, victims of propaganda- indeed, with Critical Race Theory representing a form of off-shoot moral panic more than anything else, and a paranoia towards Caucasians and towards an admittedly warped legal system- one just as warped towards the same Caucasians as it is towards any other included group.

It is doubtless in the end that Critical Race Theory will be relegated to the dustbin of history where it belongs, along with a thousand other relics of the past, and will be remembered as no more true in a century than miasmatic theory is today. However, it should be noted that works such as this present text are required to ensure such eventual capitulation of falsehood to truth- for without any pushing back, any lie or any system based on lies may flourish and grow and continue to exist unperturbed.

Tarl gets it! He understands the raison d'être of the Culture War Encyclopedia. Our culture needs a way by which anyone can instantly conjure up the facts and proof about anything contested in the culture war. Wield the radiant sword of truth in these dark times, with its sharpness discriminate between fact and fiction and by its light dispel the shadows of ignorance and deceit. We are honored that Tarl understands why we work so hard.

Speaking of which, Styx’s videos and quotes from his books as Tarl Warwick will be easily found all throughout the Encyclopedia.

INTRODUCTION

What, exactly, is critical race theory (CRT)? Has it been taught in schools? Should it be? Is it just a term some right wingers apply to American history lessons involving race that they do not want their children to be taught?

These questions tend to be divisive. Responses from the media tend to be politically motivated (at least some put on an appearance as such) and neither well informed nor honest. To nail down precisely what CRT is, we will draw almost entirely from works that critical race theorists themselves put forward as the key writings that formed their movement and from other works by those key writers insofar as they pertain to CRT.1

With CRT as with such things as progressivism, BLM, antifa and feminism, if certain aspects are pointed out, the objection will be made that these aspects are not part of the ideology or group in question. Some people try to argue that CRT does not really exist because there is no one true critical race theory doctrine, no official tax exempt CRT church and no organization registered with the government called Critical Race Theory Incorporated. They fail to see - or feign ignorance on the matter - that things like ideologies, political philosophies and informal associations do not work that way.

There is no one true/official organization representing conservatism. Does this mean conservatism can not be defined, described, criticized and so on? Or can conservatives dismiss any criticism of conservatism with, “that’s not real conservatism”, “that person is not a real conservative” or “conservatism is just an idea”?

The answer is obvious.

Yet, from experience, I can predict with almost absolute certainty that some will argue that the writers I quote from are not critical race theorists and/or that their works upon which we base our research are not representative of CRT. Others claim that there’s really no such thing as critical race theory just as some have argued that there is no such thing as cultural Marxism or that antifa is just an idea.

As we’ll see, CRT has a back-history which we will trace, it has a father figure, it has major players who have come to refer themselves and each other as critical race theorists or crits and so on, and refer to the collection of their stances as critical race theory. In fact, CRT has something approaching an unofficial cannon. I’m talking about the books and essays by these major figures in CRT that we use as our main sources.

Some capitalize the term, some did not. Helen Pluckrose and James Lindsay have capitalized the word theory but not the words critical or race when they write “critical race Theory” in their book Cynical Theories.2 According to common practice, we will not capitalize the term except when quoting sources that do as we just did. It is also a fact that these people sometimes referred to themselves and each other as critical race theorists, critical race philosophers, critical race writers and crits and there seems to be no contention among them on this matter.

As we’ll see, major universities refer to these writers as critical race theory scholars - which is how Columbia Law School describes Kimberlé W. Crenshaw,3 a crit from whom we draw our knowledge of CRT - or refer to them as, for example, “one of the nation’s foremost scholars on critical race theory” as Western State College of Law characterizes Neil Gotanda, an other crit we quote.4 In the appendix About the Crits Referenced in This Piece we demonstrate that each and every crit we quote from or reference is in fact a crit according to academia, themselves and each other.

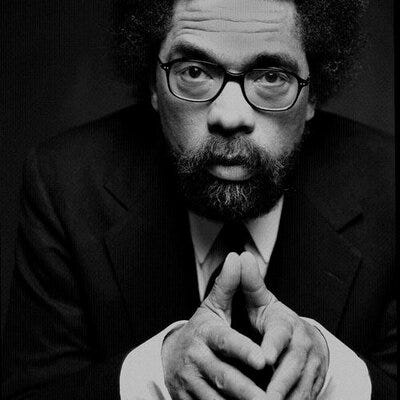

As I write these words, Cornel West is running for president. He wrote the forward to the hefty book (with tiny print and no index) Critical Race Theory - The Key Writings That Formed the Movement, published in 1995, consisting mostly of essays from years prior. The editors of that book, Kimberlé Crenshaw, Neil Gotanda, Gary Peller, Kendall Thomas are themselves crits as can be seen below in APPENDIX: About the Crits Referenced in This Piece.

An other book we will draw from heavily is Critical Race Theory - An Introduction (2017) by Jean Stefancic and Richard Delgado who is one of the few crits whose formative writings are included in Critical Race Theory - The Key Writings That Formed the Movement.5

We will also be referencing the book How to Be an Antiracist from 2019 by Ibram X. Kendi.6 Cornel West is quoted as calling Kendi “an unprecedented phenomenon”.

Until critical race theory became too controversial,7 the Biden admin endorsed8 Ibram X. Kendi, his book How to Be an Antiracist and The New York Times’ book The 1619 Project - A New Origin Story, another collection of works under one cover that will serve as a source in our look at critical race theory.9

We will also gain valuable information from the book Critical Theory - The Key Concepts (2015) by Felluga, Dino Franco Felluga and other books.

To be fair, we will look at a bit of criticism of critical race theory in book from10 from Tarl Warwick (AKA Styxhexenhammer666) and others.

Most of what we present here about critical race theory will be from these books by crits and the essays by crits contained therein that were formative to the movement.

Helen Pluckrose and James Lindsay write11

The word critical here means that its intention and methods are specifically geared towards identifying and exposing problems in order to facilitate revolutionary political change.

In a few cases, such as Ibram X. Kendi, the writer may not use the term critical race theory to refer their views but their views align with what other such writers do refer to as critical race theory. For the most part, they use the term to describe their views, they refer to themselves and each other as critical race theorists, they title their books with the term critical race theory, they are referred to by universities as being authorities in critical race theory and I provide citations for all of it, for each and every claim made. If it is possible to provide a higher quantity of proof per claim than I do in the Culture War Encyclopedia, it would be surprising.

OVERVIEW of CRT ACCORDING to CRITICAL RACE THEORISTS

Short Version

Overview of CRT According to Cornel West

Overview of CRT According to John Calmore

Overview of CRT According to Other Critical Race Theorists

Short Version

In the glossary of Critical Race Theory - an Introduction12, authors Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic define CRT as a

progressive legal movement that seeks to transform the relationship among race, racism and power.

They state13 that it is a “movement” and

a collection of activists and scholars engaged in studying and transforming the relationship among race, racism, and power.

The write14 furthermore,

Unlike traditional civil rights discourse, which stresses incrementalism and step-by-step progress, critical race theory questions the very foundations of the liberal order, including equality theory, legal reasoning, Enlightenment rationalism, and neutral principles of constitutional law

We will sometimes abbreviating Critical Race Theory - an Introduction to CRT - an Intro throughout.

Overview of CRT According to Cornel West

Critical race theory’s

main area of investigation is, as Cornel West puts it, “the historical centrality and complicity of law in upholding white supremacy (and concomitant hierarchies of gender, class, and sexual orientation)”

according to Dino Franco Felluga15 in Critical Theory - The Key Concepts.16

Dr. Cornel West also wrote,17

Critical Race Theory is the most exciting development in contemporary legal studies. This comprehensive movement in thought and life - created primarily though not exclusively, by progressive intellectuals of color - compels us to confront critically the most explosive issue in American civilization: the historical centrality and complicity of law in upholding white supremacy (and concomitant hierarchies of gender, class, and sexual orientation).

More poetically, West wrote,18

Critical Race Theory is a gasp of emancipatory hope that law can serve liberation rather than domination.

It may help the reader to be aware that West’s definitions of terms like liberation and domination may be quite different than their own. Also, there is the little matter of CRT’s stance on racial separatism which we will come to below.

West made a name for himself outside of CRT but he is something of an honorary crit as witnessed by the fact that he wrote the forward to Critical Race Theory - the Key Writings That Formed the Movement.

Overview of CRT According to John Calmore

The essay Critical Race Theory Archie Shepp and Fire Music Securing An Authentic Intellectual Life in A Multicultural World by John O. Calmore was included in Critical Race Theory - The Key Writings That Formed the Movement (1995)19 by the editors of that book who write20 Calmore provides

a systematic description of Critical Race Theory

I want to be sure to not give the reader the impression that Calmore’s “systematic description” of CRT is complete or even systematic. That is their claim, not mine. However his essay is included as one of the key writings in Critical Race Theory - The Key Writings That Formed the Movement and they clearly approve of his description. Hence, we heed it here.

Calmore writes21 that CRT begins with the view that race is a social construct. This will be elaborated upon in the section below in the section dedicated to race as a social construct and in the entry in the Culture Ware Encyclopedia on race.

He writes of22

critical race theory's radical assessment orientation

and adds23 that

critical race theory recognizes that revolutionizing a culture begins with the radical assessment of it.

Further along these lines, he writes that CRT is activist in nature24 and that it is “oppositional scholarship”, that it takes an adversarial position to general academia and society.25 He writes further along these lines throughout. We will discuss this below. Also, see my piece Non-Neutrality & Oppositional Scholarship in Critical Race Theory. He writes about the race conscious aspect of CRT.26 We will expand on race consciousness later.

CRT is eclectic according to Calmore.27

Critical Race Theory recombines and extends existing means of legal redress; hence it is necessarily eclectic, incorporating what seems helpful from various disciplines, doctrines, styles, and methods.

Indeed, this is so as the reader will see in the course of this piece. CRT is intersectional according to Calmore.28 We will explore intersectionality in CRT later.

He also place importance on ‘voice’ in CRT.29 Crits use the term voice to mean something like a distinctive style of communication. When an artist is said to have found their voice, it means that one can tell the art was created by that artist just from the art itself. In CRT, there is a focus on what they sometimes call voice of color, the voice-of-color thesis, sometimes called the unique voice of color thesis. See the section below on voice of color for more.

Calmore discusses CRT’s opposition to color blindness, that is, the non-neutral stance on skin color.30 In other words, CRT is race conscious, meaning that in CRT people are judged by the color of their skin. We will discuss all of these below.

Calmore also states that CRT is anti-essentialist,31 opposed to assimilation, against racial integration,32 concerned with culture33 and cultural racism.34 All of these will be explored.

Overview CRT According to Other Critical Race Theorists

In the introduction to Critical Race Theory - the Key Writings That Formed the Movement (which we will sometimes abbreviate to CRT - Key Writings), it states35 about the various critical race theorists whose writings the book contains that

As these writings demonstrate, there is no canonical set of doctrines or methodologies to which we all subscribe. Although Critical Race Theory scholarship differs in object, argument, accent, and emphasis, it is nevertheless unified by two common interests.

The first is to understand how a regime of white supremacy and its subordination of people of color have been created and maintained in America, and, in particular, to examine the relationship between that social structure and professed ideals such as “the rule of law” and “equal protection.”

More along these lines below, particularly in the sections on race consciousness and racial realism. These critical race theorist editors continue,

The second is desire not merely to understand the vexed bond between law and racial power but to change it.

Above we saw a glimpse of Calmore’s treatment of these proactive, activist, confrontational and oppositional sides and we will explore them below.

These crit editors add the following, citing Alan Freeman to whom we will return in the history section,36

The aspect of our work which most markedly distinguishes it from conventional liberal and conservative legal scholarship about race and inequality is a deep dissatisfaction with traditional civil rights discourse. . . The construction of “racism” from what Alan Freeman terms the “perpetrator perspective” restrictively conceived racism as an intentional, albeit irrational, deviation by a conscious wrongdoer from an otherwise neutral, rational, and just ways of distributing jobs, power, prestige, and wealth. The adoption of this perspective allowed a broad cultural mainstream both explicitly to acknowledge the fact of racism and, simultaneously, to insist on its irregular occurrence and limited significance. As Freeman concludes, liberal race reform thus served to legitimize the basic myths of American meritocracy.

In Gary Peller’s depiction, this mainstream civil rights discourse on “race relations” was constructed in this way partly as a defense against the more radical ideologies of racial liberation presented by the Black Nationalist and Black Consciousness movements of the sixties and early seventies . . .

In the construction of “racism” as the irrational and backward bias of believing that someone’s race is important, the American cultural mainstream neatly linked the black left to the white racist right: according to this quickly coalesced consensus, because race-consciousness characterized both white supremacists and black nationalists, it followed that both were racists. The resulting “center” of cultural common sense thus rested on the exclusion of virtually the entire domain of progressive thinking about race within colored communities. With its explicit embrace of race-consciousness, Critical Race Theory aims to reexamine the terms by which race and racism have been negotiated in American consciousness, and to recover and revitalize the radical tradition of race-consciousness among African-Americans and other peoples of color - a tradition that was discarded when integration, assimilation and ideal of color-blindness became the official norms of racial enlightenment.

By now you get the idea that we will explore race consciousness below. A bit further on37 they make clear that they pose an

opposition to civil rights discourse

and go on to argue38 that civil rights reform - with the establishment of laws that establish that people are to be judged not by the color of their skin but by the content of their character - is counter productive because they are too moderate. They express39 their unhappiness with civil rights reform for the role it

played in the deradicalization of racial liberation movements.

They go on to argue that laws against overt racism allow subtle racism to continue unchecked. In his formative essay Racial Realism in particular, the “intellectual father figure” of CRT,40 Derrick A. Bell Jr. argues that racial equality is impossible to achieve and that people would do well to give up on the hope.41 Critical race theorists do not offer a better alternative as far as I have been able to find after reading over 1,573 pages across 5 books and many essays worth of writing about CRT by critical race theorists (see the bibliography).

HISTORY of CRT

Postmodernism Paves the Way for CRT

A Brief Background in Postmodernism

Beginning of CRT & the Coining of the Term

From Radical Feminism & Critical Legal Studies to CRT

CRT’s Marxism

CRT’s Anti-Liberal Past & Present

Alternative Course

Foundational CRT

Postmodernism Paves the Way for CRT

A Brief Background in Postmodernism

In Cynical Theories - How Activist Scholarship Made Everything about Race, Gender and Identity and Why This Harms Everybody (first published in 2020),42 authors Helen Pluckrose and James Lindsay expound43 upon the prehistory and history of

a radical worldview that came to be known as “postmodernism”

which, they they profess in detail, paved the way for CRT.

[CITATION HERE]

They write44 that postmodernism

arguably emerged between 1950 and 1970 - the exact dates depending upon whether one is primarily interested in its artistic or social aspects. The earliest changes began in art - we can trace them as far back as the 1940s, in the words of artists such as Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges -

We go over a bit more postmodern prehistory and history in the section on postmodernism in the Culture War Encyclopedia than we do here but, as Pluckrose and Lindsay continue and with which I concur, it is he later 1960’s that are important for understanding poltical postmodernism because this is when history

witnessed the emergence of French social Theorists such as Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida and Jean-Francois Lyotard.

Also in the section on Postmodernism in the Culture War Encyclopedia, we note that Britannica describes postmodernism as being marked by a

general suspicion of reason

and a “broad” skepticism, subjectivism and/or relativism along with a keen focus on the role ideology plays in the establishment and maintanance of economic and political power. We write that Britannica furthemore states that postmodernism is mainly

a reaction against the intellectual assumptions and values of the modern period in the history of Western philosophy (roughly, the 17th through the 19th century). Indeed, many of the doctrines characteristically associated with postmodernism can fairly be described as the straightforward denial of general philosophical viewpoints that were taken for granted during the 18th-century Enlightenment, though they were not unique to that period.

Britannica also states that the most important viewpoints of the 18th-century Enlightenment were that

1. There is an objective natural reality, a reality whose existence and properties are logically independent of human beings—of their minds, their societies, their social practices, or their investigative techniques. Postmodernists dismiss this idea as a kind of naive realism. Such reality as there is, according to postmodernists, is a conceptual construct, an artifact of scientific practice and language. This point also applies to the investigation of past events by historians and to the description of social institutions, structures, or practices by social scientists.

2. The descriptive and explanatory statements of scientists and historians can, in principle, be objectively true or false. The postmodern denial of this viewpoint—which follows from the rejection of an objective natural reality—is sometimes expressed by saying that there is no such thing as Truth.

3. Through the use of reason and logic, and with the more specialized tools provided by science and technology, human beings are likely to change themselves and their societies for the better. It is reasonable to expect that future societies will be more humane, more just, more enlightened, and more prosperous than they are now. Postmodernists deny this Enlightenment faith in science and technology as instruments of human progress. Indeed, many postmodernists hold that the misguided (or unguided) pursuit of scientific and technological knowledge led to the development of technologies for killing on a massive scale in World War II. Some go so far as to say that science and technology—and even reason and logic—are inherently destructive and oppressive, because they have been used by evil people, especially during the 20th century, to destroy and oppress others.

4. Reason and logic are universally valid—i.e., their laws are the same for, or apply equally to, any thinker and any domain of knowledge. For postmodernists, reason and logic too are merely conceptual constructs and are therefore valid only within the established intellectual traditions in which they are used.

5. There is such a thing as human nature; it consists of faculties, aptitudes, or dispositions that are in some sense present in human beings at birth rather than learned or instilled through social forces. Postmodernists insist that all, or nearly all, aspects of human psychology are completely socially determined.

6. Language refers to and represents a reality outside itself. According to postmodernists, language is not such a “mirror of nature,” as the American pragmatist philosopher Richard Rorty characterized the Enlightenment view. Inspired by the work of the Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure, postmodernists claim that language is semantically self-contained, or self-referential: the meaning of a word is not a static thing in the world or even an idea in the mind but rather a range of contrasts and differences with the meanings of other words. Because meanings are in this sense functions of other meanings—which themselves are functions of other meanings, and so on—they are never fully “present” to the speaker or hearer but are endlessly “deferred.” Self-reference characterizes not only natural languages but also the more specialized “discourses” of particular communities or traditions; such discourses are embedded in social practices and reflect the conceptual schemes and moral and intellectual values of the community or tradition in which they are used. The postmodern view of language and discourse is due largely to the French philosopher and literary theorist Jacques Derrida (1930–2004), the originator and leading practitioner of deconstruction.

7. Human beings can acquire knowledge about natural reality, and this knowledge can be justified ultimately on the basis of evidence or principles that are, or can be, known immediately, intuitively, or otherwise with certainty. Postmodernists reject philosophical foundationalism—the attempt, perhaps best exemplified by the 17th-century French philosopher René Descartes’s dictum cogito, ergo sum (“I think, therefore I am”), to identify a foundation of certainty on which to build the edifice of empirical (including scientific) knowledge.

8. It is possible, at least in principle, to construct general theories that explain many aspects of the natural or social world within a given domain of knowledge—e.g., a general theory of human history, such as dialectical materialism. Furthermore, it should be a goal of scientific and historical research to construct such theories, even if they are never perfectly attainable in practice. Postmodernists dismiss this notion as a pipe dream and indeed as symptomatic of an unhealthy tendency within Enlightenment discourses to adopt “totalizing” systems of thought (as the French philosopher Emmanuel Lévinas called them) or grand “metanarratives” of human biological, historical, and social development (as the French philosopher Jean-François Lyotard claimed). These theories are pernicious not merely because they are false but because they effectively impose conformity on other perspectives or discourses, thereby oppressing, marginalizing, or silencing them. Derrida himself equated the theoretical tendency toward totality with totalitarianism.

We can look at these 8 viewpoints that postmodernism opposes according to Britannica - however applicable it may or may not be - as an 8 point description of postmodernism. Accordingly, postmodernism would involve:

a denial that reality exists outside of human conceptions about what they think of as reality

a denial that there is such thing as truth. History and science do not offer objective truth. That is, there is no such thing as THE truth, as in one single objective reality as opposed to false conceptions of reality

a denial of human progress and that which makes this progress possible: the Enlightenment ideals, reason, logic, science, technology, ethics, humanity and so on

a denial that logic and reason are universal, that they apply equally to all situations regardless of the cultural context, denial that this Enlightenment style view is not one of many incompatible but equally valid views, such as irrational and/or illogical world views

a denial that humans have some inherent nature, that they can be born heteroxual or homosexual, smart or dull, or that humans have many - if any - aspects that are not socially conditioned rather than biologically determined such as gender, artistic aptitude or athletic potential

a denial that language points to aspects of a reality that exists outside of language

a denial that we can begin with the dictum “I think, therefore I am” as a first principle and from there gain knowledge using evidence and principles supported by the first principle

a denial that it is possible, in principle or in practice, to construct theories with explanatory power. For example, the theory of gravity is of no use to us if we want to decide if we should jump off a cliff or not because the outcome is entirely uncertain and any theories about what may happen are equally valid. So, the views that we may fly if we jump off a cliff or be carried safely to the Jupiter by blue space crabs are no more or less valid that the view that we will fall to earth if we jump off a cliff.

Although, as Pluckrose & Lindsay write,45

postmodernism is difficult to define, perhaps by design

it does indeed seem they define the undefinable in their first chapter, 1 POSTMODERNISM, by laying out what they say are the 2 principles and 4 themes of postmodernism46 (to which we will return) after presenting the 4 pillars of postmodernism according to Walter Truen Anderson47 and the central themes of postmodernism according to Steinar Kvale, director of the Center of Qualitative Research and professor of psychology.48

They write49 that author Walter Anderson’s 4 pillars of postmodernism are as follows,

The social construction of the concept of the self: Identity is constructed by many cultural forces and is not given to a person by tradition;

Relativism of moral and ethical discourse: Morality is not found but made. That is, morality is not base on cultural or religious tradition, nor is it the mandate of Heaven, but is constructed by dialogue and choice. This is relativism, not in the sense of being nonjudgmental, but in the sense of believing that all forms of morality are socially constructed cultural worldviews;

Deconstruction in art and culture: The focus is on endless playful improvisation and variations on themes and a mixing of “high” and “low” culture; and

Globalization: People see borders of all kinds as social constructions that can be crossed and reconstructed and are inclined to take their tribal norms less seriously.50

They write51 that according to Steinar Kvale, director of the Center of Qualitative Research and professor of psychology, the central themes of postmodernism include:

Doubt that human truths can accurately represent reality

Denial of the universal (plurality)

Societies (plural) use language to create their own local realities (plural)

They go on to write52 that Kvale explains that these central themes of postmodernism

resulted in an increased interest in narrative and storytelling, particularly when “truths” are situated within particular cultural constructs, and a relativism that accepts that different descriptions of reality cannot be measured against one another in any final - that is, objective - way.53

The key observation, following54 is that the postmodern turn brought about an important shift away from the modernist dichotomy between the objective universal and the subjective individual and toward local narratives (and the lived experiences of their narrators). In other words, the boundary between that which is objectively true and that which is subjectively experienced ceased to be accepted. The perception of society as formed of individuals interacting with universal reality in unique ways - which underlies the liberal principles of individual freedom, shared humanity, and equal opportunities - was replaced by multiple allegedly equally valid knowledges and truths, constructed by groups of people with shared markers of identity related to their positions in society. Knowledge, truth, meaning, and morality are therefore, according to postmodernist thinking, culturally constructed and relative products of individual cultures, none of which posses the necessary tools or terms to evaluate the others.

To return to the 2 principles and 4 themes of postmodernism according to Pluckrose and Lindsay, they offer their own description of these in Cynical Theories55 beginning with an acknowledgement that postmodernists can be strikingly different in their approach to their reaction to Enlightenment thought with regard to objective knowledge and universal truths in particular. They write that despite this, a handful of themes running through postmodernist ‘discourse’ can be discerned. They name and describe as we’ll see. They also write56 that the postmodernism involves, at its core, 2 inseparable principles and 4 themes.

The 2 principles of postmodernism are:

the postmodern knowledge principle

and

the postmodern political principle

and the 4 major themes of postmodernism are:

The blurring of boundaries

The power of language

Cultural relativism

The loss of the individual & the universal

They write about these57 that together, with these 2 principles and 4 themes, we can recognize postmodern conception and comprehend its workings. According to them,58 these fundamental principles of “Theory” have survived, mostly unaltered, since its deconstructive early days to the zealous activism of the two thousand teens and two thousand twenties. They write59 that this

arose from various theoretical approaches in the humanities, particularly that going by the term “cultural studies,” mainly over the last century, and developed into the postmodernist Social Justice scholarship, activism, and culture we see today.

We will now look at Pluckrose’s and Lindsay’s 2 principles and 4 themes at some depth.

Principle 1 - The Postmodern Knowledge Principle

Pluckrose and Lindsay write60 of the postmodern knowledge principle that it is

radical skepticism about whether objective knowledge or truth is obtainable and a commitment to cultural constructivism

which, they write,61 leads to a preoccupation with the 4 main themes as they see it. We will return to these 4 main themes below. For now, we must note that as postmodernism - or at least as influential thinkers who were influenced by postmodern thinkers - became focused on activism (“applied postmodernism”), this principle was modified. They write62 that this principle

has been largely retained, with one important provisio: under applied postmodern thought, identity and oppression based on identity are treated as known features of objective reality. That is, the conception of society as comprised of systems of power and privilege that construct knowledge is assumed to be objetively true and intrinsically tied to social constructions of identity.

We will look at applied postmodernism in an other section ahead. Earlier, they wrote63 that

postmodern approaches to knowledge inflate a small, almost banal kernel of truth - that we are limited in our ability to know and must must express knowledge through language, concepts and categories - to insist that all claims to truth are value-laden constructs of culture. This is called cultural constructivism or social constructivism. The scientific method, in particular, is not seen as a better way of producing and legitimizing knowledge than any other, but as one cultural approach among any, as corrupted by biased reasoning as any other.

Let us pause here to consider what should go without saying, one would hope, but just to be sure, as the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy puts it under their entry on the scientific method,

science is an enormously successful human enterprise. The study of scientific method is the attempt to discern the activities by which that success is achieved.

Science is, as Britannica puts it,

any system of knowledge that is concerned with the physical world and its phenomena and that entails unbiased observations and systematic experimentation.

Even a dog can experiment with different strategies in attempt to open a bag of doggie treats. A toddler can experiment in a systematic and rational manner to gain access to a high shelf to obtain a box of cookies and the contents therein. The point is that the scientific approach is universal, not culture bound. Some people may argue otherwise. These same people would not be likely to choose an Amazonian Witoto healer over a UPMC oncologist to treat their brain tumor were they to have one and be forced to choose one or the other. Imagine a postmodernist who subscribes to cultural relativism has a very painful toothache. You offer to pay for professional dentist appointment or pay for a new age crystal healer to deal with the issue. Which will they choose?

Imagine that a tribe on the other side of the river believes that if you hold 2 nuts or berries in one hand and 2 nuts or berries in the other hand, you hold a total of 5 nuts or berries. Is this view just as valid as your tribe’s view that 2 nuts/berries plus 2 more nute/berries adds up to 4 nuts/berries. Your tribe can respect the other trib’s righ to believe whatever they want, but when it comes time to trade nuts and berries with that tribe, reality will make itself known and undeniable. A postmodernist may say that the view that 2 = 2 = 4 for all tribes, all cultures and all people is a metanarrative. If that is a metanarrative, then this demonstrates the invalidity of the anti-metanarrative view.

At any rate, Pluckrose and Lindsay continue,64

Cultural constructivism is not the belief that reality is literally created by cultural beliefs - it doesn’t argue, for instance, that when we erroneously believed that the Sun went around the Earth, our beliefs had any influence over the solar system and its dynamics. Instead, it is the position that humans are so tied into their cultural frameworks that all truth or knowledge claims are merely representations of those frameworks - we have decided that “it is true” or “it is known” that the Earth goes round the Sun because of the way we establish truth in our current culture. That is, although reality doesn’t change in accordance with our beliefs, what does change is what we are able to regard as true (or false - or “crazy”) about reality. If we belonged to a culture that produced and legitimated knowledge differently, within that cultural paradigm it might be “true” that, say, the Sun goes around the Earth. Those who would be regarded as “crazy” to disagree would change accordingly.

They write elsewhere65 about this that,

postmodernism rests upon a broad rejection of the correspondence theory of truth: that is, the position that there are objective truths and that they can be established as true by their correspondence with how things actually are in the world.66(FOOTNOTE: Here the authors place this footnote: Rorty makes this case ten years earlier in Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1979) That there are real truths about an objective reality “out there” and that we can come to know them is, of course, at the root of Enlightenment thinking and central to the development of science. Profoundly radical skepticism about this idea is central to postmodern thinking about knowledge.

French philosopher Michel Foucault - a central figure of postmodernism - expresses this same doubt when he argues that, “in any given culture at any given moment, there is always only one episteme that defines the contradictions of possibility of all knowledge, whether expressed in a theory or silently invested in a practice.”67 Foucault was especially interested in the relationship between language, or, more specifically, discourse (ways of talking about things), the production of knowledge, and power. He explored these ideas at length throughout the 1960s, in such influential works as Madness and Civilization (1961), The Birth of the Clinic (1963), The Order of Things (1966), and The Archaeology of Knowledge (1969).68 For Foucault, a statement reveals not just information but also the rules and conditions of a discourse. These then determine the construction of truth claims and knowledge. Dominant discourses are extremely powerful; because they determine what can be considered true, thus applicable, in a given time and place. Thus, sociopolitical power is the ultimate determiner of what is true in Foucault’s analysis, not correspondence with reality. Foucault was so interested in the concept of how power influences what is considered knowledge that in 1981 he coined the term “power-knowledge” to convey the inextricable link between powerful discourses and what is known. Foucault called a dominant set of ideas and values an episteme because it shapes how we identify and interact with knowledge.

In The Order of Things, Foucault argues against objective notions of truth and suggests we think instead of in terms of “regimes of truth,” which change according to the specific episteme of each culture and time. As a result, Foucault adopted the position that there are no fundamental principles by which to discover truth and that all knowledge is “local” to the knower69 - ideas which form the basis of the postmodern knowledge principle. Foucault didn’t deny that a reality exists, but he doubted the ability of humans to transcend our cultural biases enough to get at it.

The main takeaway from all this is that postmodern skepticism is not garden-variety skepticism, which might also be called “reasonable doubt.” The kind of skepticism employed in the sciences and other rigorous means of producing knowledge asks, “How can I be sure this proposition is true?” and will only tentatively accept as a provisional truth that which survives repeated attempts to disprove it. These propositions are put forth in models, which are understood to be provisional conceptual constructs, which are used to explain and predict phenomena and are judged according to their ability to do so. The principle of skepticism common among postmodernists is frequently referred to as “radical skepticism.” It says, “All knowledge is constructed: what is interesting is theorizing about why knowledge got constricted this way.” Thus, radical skepticism is markedly different from the scientific skepticism that characterized the Enlightenment. The postmodern view wrongly insists that scientific thought is unable to distinguish itself as especially reliable and rigorous in determining what is and isn’t true.70 Scientific reasoning is construed as a metanarrative - a sweeping explanation of how things work - and postmodernism is radically skeptical of all such explanations. In postmodern thinking, that which is known is only known within the cultural paradigm that produced the knowledge and is therefore representative of its systems of power. As a result, postmodernism regards knowledge as provincial and intrinsically political.

This view is widely attributed to the French philosopher Jean-François Lyotard, who critiqued science, the Enlightenment, and Marxism. Each of these projects was, for Lyotard, a prime example of a modernist or Enlightenment metanarrative. Ultimately, Lyotard feared that science and technology were just one “language game” - one way of legitimating truth claims - and that they were taking over all other language games. He mourned the demise of small local “knowledges” passed on in narrative form and viewed the loss of meaning-making intrinsic to scientific detachment as a loss of valuable narratives. Lyotard’s famous characterization of postmodernism as a “skepticism towards metanarratives” has been extremely influential on the development of postmodernism as a school of thought, analytical tool, and worldview.71

This was the great postmodern contribution to knowledge and knowledge production. It did not invent the skeptical reevaluation of well-established beliefs. It did, however, fail to appreciate that scientific and other forms of literal reasoning (such as arguments in favor of democracy and capitalism) are not so much metanarratives (though they can adopt these) as imperfect but self-correcting processes that apply a productive and actionable form of skepticism to everything, including themselves. This mistake led them into their equally misguided political project.

They also write,72

This generalized skepticism about the objectivity of truth and knowledge - and commitment to regarding both as culturally constructed - leads to a preoccupation with four main themes: the blurring of boundaries, the power of language, cultural relativism, and the loss of the individual and the universal in favor of group identity.

We will enumerate and describe these after the 2nd principle below.

Principle 2 - The Postmodern Political Principle

Pluckrose and Lindsay write73 (Page 31) of the postmodern political principle that it is

a belief that society is formed of systems of power and hierarchies which decide what can be known and how.

For a concrete example, consider Facebook or Youtube where one can be sanctioned for discussing certain matters. Facebook states that “hate speech” is not allowed on their platform. Youtube also states as much. What is “hate speech”? Stating “men are not women” for example, or discussing any number of partisan issues can cause Facebook and/or Youtube to silence a person. Additionally, people have been punished by their banks and other financial services in full swing of the authoritarian left curve. See Financial Unpersoning by Justin Trouble for more on that.

Also, Facebook, Youtube presumed to decide what cold or could not be communicated about the flu-19. One could not discuss COVID-19 unless one only expressed views that conform to a very narrow officially sanctioned range. Try to do a search, for example, on “restrictions on covid discussion on facebook youtube”. In 2019, my official Twitter account was suspended forever because I refused to delete a tweet wherein I wrote that Martin Luther King Jr was against riots and included a video clip of an interview wherein Dr. King makes that perfectly clear. It was in the context of a thread where a lot of leftists were arguing that MLK said that “riots are the language of the unheard”, which Dr. King did indeed say right before he condemned them. I have repeatedly been suspended from both Facebook and Youtube for stating facts like “Islam does not mean peace, it means submission” and I have been permanently kicked off Facebook for something factually correct but triggering. I forget what it exactly it was because I had been suspended so many times for rediculous reasons.

I used Facebook and Youtube to communicate things that many people would not otherwise know. I had a few thousand friends on Facebook before they kicked me off and on Youtube I have about 23,000 subscribers and about 14,000,000 views before they shadowbanned me. (FOOTNOTE) Much of what I communicated was, to my knowledge, not communicated by anyone else.(FOOTNOTE) In some cases, I communicated to the viewers my own exclusives, exposés and so on.

What can not be communicated can not be known. If one is punished for communicating certain things or terrorized into not discussing certain things, those things will become obscure and unknown. People have been punished for communicating wrongthink by having their ability to communicate limited or blocked. Some have been punished for communicating wrongthink through what I call Financial Unpersoning.

They silenced Julian Assange, did they not? They sabotaged James O’Keefe and his Project Veritas. (SEE FOORNOTE) On August 6, 2018, Apple, Facebook, Spotify and Youtube all kicked Alex Jones off their platforms.[FOOTNOTE: August 6, 2018NOTE TO SELF - DID THEY CITE DIFFERENT REASONS AND DIFFERENT CONTENT FROM JONES? IF O THEN IT’S NOT AS IF JONES ONE DAY DID SOMETHING PARTICULARLY BAD AND THAT’S WHY THEY ALL BANNED HIM ON THE SAME DAY] I am sure they did not plan that with each other because that would require that they conspire and we all know that it is crazy to believe that people or groups would conspire. That’s insane. Nobody makes agreement in secret for mutual benefit. Conspiracy theories are for right-wing nut-jobs. Besides, Twitter waited until the 6th of the following month before axing Jones so it was not a conspiracy.

If you recall, these social media giants collude with the federal government. One could fairly say they worked in concert. The merging of government and industry is a major aspect of fascism. See, for example, Fourteen Defining Characteristics of Fascism in which they write74

Controlled Mass Media

The media is directly or indirectly controlled by the government and that

Censorship is very common

The point here is that at least to some degree, it is indeed true that systems of power decide what can and can not be known.

Getting back to Pluckrose and Lindsay, they also write75 of the postmodern political principle that it involves the belief

that powerful forces in society essentially order society into categories hierarchies that are organized to serve their own interests. They effect this by dictating how society and its features can be spoken about and what can be accepted as true. For example, a demand that a someone provide evidence and reasoning for their claims will be seen through a postmodernist Theoretical lens as a request to participate in a system of discourses and knowledge production that was built by powerful people who valued these approaches and designed them to exclude alternative means of communicating and producing “knowledge.” In other words, Theory views science as having been organized in a way that serves the interests of the powerful people who established it - white Western men - while setting up barriers against the participation of others. Thus, the cynicism at the heart of Theory is evident.

This seems to imply that unlike others, Western man is rational and scientific. This is clearly not so. Non-Western culture has been rational and scientific. Also, like all others, Western culture can be quite irratonal and unscientific.

Also, this argument that the rational, scientific narrative of things is no more valid than alternatives seems to be an attempt to give college students and leftists in general an excuse to disregard reality when it serves them to do so. They can identify as a transabled cat for which 2 + 2 = 5.

Pluckrose and Lindsay also write,76

Postmodernism is characterized politically by its intense focus on power as the guiding and structuring force of society, a focus which is codependent on the denial of objective knowledge. Power and knowledge are seen as inextricably entwined - most explicitly in Foucault’s work, which refers to knowledge as “power knowledge.” Lyotard also describes a “strict interlinkage”77 between the language of science and that of politics and ethics, and Derrida was profoundly interested in the power dynamics embedded in hierarchal binaries of superiority and subordination that he believed exist within language. Similarly, Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari saw humans as coded within various systems of power and constraints and free to operate only within capitalism and the flow of money. In this sense, for postmodern Theory, power decides not only what is factually correct but also what is morally good - power implies domination, which is bad, whereas subjugation implies oppression, the disruption of which is good. These attitudes were prevailing mood at the Sorbonne in Paris through the 1960s, where many of the early Theorists were strongly intellectually influenced.

Furthermore, they claim78 that

postmodernists do not necessarily see the system of oppression as the result of a consciously coordinated, patriarchal, white supremacist, heteronormative conspiracy. Instead, they regard it as the inevitable result of self-perpetuating systems that privilege some groups over others, which constitute an unconscious, uncoordinated conspiracy inherent to systems involving power. They believe, however, that those systems are patriarchal, white supremacist, and heteronormative, and therefore necessarily grant unfair access to straight, white Western men and work to maintain that statues quo by excluding the perspectives of women and of racial and sexual minorities.

We must note that they argue that79

postmodern Theory runs the overtly left-wing idea that oppressive power structures constrain humanity and are to be deplored. This results in an ethical imperative to deconstruct, challenge, problematize (find and exaggerate the problems within), and resist all ways of thinking that support oppressive structures of power, the categories relevant to power structures, and the language that perpetuates them - thus embedding a value system into what might have been a moderately useful descriptive theory.

This impulse generates a parallel drive to prioritize the narratives, systems, and knowledges of marginalized groups.

Along these lines, and to make their point, they quote Foucault,80 as an example;

“…my position leads not to apathy but to a hyper - and pessimistic activism…”

Additionally, they write,81

Postmodernism did not invent ethical opposition to oppressive power systems and hierarchies - in fact, much of the most significant social and ethical progress occurred during the preceding periods that it rejects and continues to be brought about by applying the methods of liberalism. The postmodern approach to ethically driven social critique is intangible and unfalsifiable.

It seems fair to add that some of it is not ethically driven but rather predeliction toward nihilistic tantrums. But this is beside their point here, that postmodernism is not about truth. Nor is it a philosophy by definition, at least according to those who are considered to be the most important of the postmodernists.

4 Major Themes of Postmodernism

Again, Pluckrose and Lindsay wrote that from the Postmodern Knowledge Principle (described above) came, a preccupatiom with 4 main themes of posmodernism.82

The blurring of boundaries

The power of language

Cultural relativism

The loss of the individual and the universal

Theme 1 - The Blurring of Boundaries

They describe this83

Radical skepticism as to the possibility of objective truth and knowledge, combined with a belief in cultural constructivism in service of power, results in a suspicion of all the boundaries and categories that previous thinkers widely accepted as true. These include not only the boundaries between objective and subjective and between truth and belief, but also those between science and the arts (especially for Lyotard), the natural and the artificial (particularly for Baudrillard and Jameson), high and low and culture (see Jameson), man and other animals, and man and machine (in Deleuze), and between different underdstandings of sexuality and gender as well as health and sickness (see, especially, Foucault). Almost every socially significant category has been intentionally complicated and problematized by postmodern Theorists in order to deny such categories any objective validity and disrupt the systems of power that might exist across them.

They add84 that in the case of “applied postmodernism,” the blurring the boundaries theme

is most evident in postcolonial and queer Theories, which are both explicitly centered on ideas of fluidity, ambiguity, indefinability, and hybridity - all of which blur or even demolish the boundaries between categories. Their common concern with what they call “disrupting boundaries” follows from Derrida’s work on the hierarchal nature and meaninglessness of linguistic constructions. this theme is less evident in critical race Theory, which can be quite black-and-white (double meaning intended), but, in practice, the intersectional feminist element of critical race Theory encompasses many identity categories simultaneously and tries to be inclusive of “different ways of knowing".” This results in a messy mixing of the evidenced with experiential, in which a personal intepretationof lived experience (often informed - or misinformed - in Theory) is elevated to the status of evidence (usually of Theory).

Theme 2 - The Power of Language

They write of this theme as follows,85

Under postmodernism, many ideas that had previously been regarded as objectively true came to be seen as mere constructions of language. Foucault refers to them as “discourses” that construct knowledge; Lyotard, expanding upon Wittgenstein, calls them “language games” that legitimize knowledges. In postmodern thought, language is believed to have enormous power to control society and how we think and thus is inherently dangerous. It is also seen as an unreliable way of producing and transmitting knowledge.

The obsession with language is at the heart of postmodern thinking and key to its methods. Few thinkers exhibit the neurotic postmodern fixation upon words more explicitly than Jacques Derrida, echo, in 1967, published three texts - Of Grammatology, Writing and Difference, and Speech and Phenomena - in which he introduced a concept that would become very influential in post modernism: deconstruction. In these works, Derrida rejects the commonsense idea that words refer straightforwardly to things in the real world.(34) Instead, he insists that words refer only to other words and to the ways in which they differ from one another, thus forming chains of “signifiers.” which can go off all directions with no anchor - this being the meaning of his famous and often-mistranslated phrase, “there is nothing [read: no meaning] outside of text.”(35) For Derrida, meaning is always relational and deferred, and can never be reached and exists only in relation to the discourse in which it is emdedded. This unreliability of language, Derrida argues, means that it cannot represent reality or communicate it to others.

In this understanding, language operates hierarchically through binaries, always placing one element above another to make meaning. For example, “man” is defined in opposition to “woman” and taken to be superior. Additionally, for Derrida, the speaker’s meaning has no more outweigh impact. Thus, if someone says that there are certain features of a culture that can generate problems, and I choose to interpret this statement as a dog whistle about the inferiority of that culture and take offense, there is no space in Derridean analysis to insist that my offense followed from a misunderstanding of what had been said. The author’s intentions are irrelevant, when those can be known, due to Derrida’s adaptation of Roland Barthes’ concept of “the death of the author.”(36) Consequently, since discourses are believed to create and maintain oppression, they have to be carefully monitored and deconstructed. This has obvious implications for moral and political action.

The most common postmodernist response to this derives from Derrida’s proposed solution: to read “deconstructively,” by looking for internal inconsitencies (aporia) in which a text contradicts and undermines itself and its own purposes when the words are examined closely enough (which is to say, too closely and, especially since the 1990s, with an agenda - Theory’s normative agenda). In practice, deconstructive approaches to language therefore look very much like nipicking at words in order to deliberately miss the point.

They write furthermore86 that with “applied postmodernism,” the power of language theme

The power and danger of language are foregrounded in all the newer applied postmodern Theories. “Discourse analysis” plays a central role in all those fields; scholars scrutinize language closely and interpret it according to Theoretical frameworks. For example, many films are watched “closely” for problematic portrayals and then disparaged, even if their themes are broadly consistent with Social Justice.(32) Additionally, the idea that words are powerful and dangerous has now become widespread and underlies much scholarship and activismaround discursive (or verbal) violance, safe spaces, microaggressions, and trigger warnings.

Theme 3 - Cultural Relativism

They write,87 regarding this third theme,

Because, in postmodern Theory, truth and knowledge are believed to have been constructed by the dominant discourses and language gaes that operate within society, and because we cannot step putside our own system and categories and therefore have no vantage point from which to examine them, Theory insists that no one set of cultural norms can be said to be better than any other. For postmodernists, any meaningful critiques of a culture’s values and ethics from within a different cultureis impossible, since each culture operates under different concepts of knowledge and speaks only from its own biases. All such critique is therefore erroneous at best and a moral infraction at worst, since it presipposes one’s own culture to be objectively superior.

Moreover, Theory insists that although sone can critique oen’s own culture from within the system, one can only do so using discourses available in that system, which limits its ability to change. Which discourses one can use is largely dependendent on one’s position within the sytem, therefore critiques can be accepted or dismissed depending on a politival assessement of the status of the critic’s position. In particular, criticism from any position deemed powerful tends to be dismissed because it is asssumed either to be ignorant (or dismissive) of tthe realities of oppression, by definition, or a cynical attempt to serve the critic’s own interests. The postmodern belief that individuals are vehicles of dosciurses of power, depending on where they stand in relation to power, makes cultural critique completely hopeless except as a weapon in the hand of those Theorized to be marginalized or oppressed.

They add88 that in the case of “applied postmodernism,” the cultural relativist theme

Cultural relativism is, or course, most pronounced in postcolonial Theory, but the widespread use of intersectionality in Social Justice scholarship and activism and he understanding of the West as the pinnacle of an oppressive power structure have made cultural relativism a norm in all oppressive power structure have made cultural relativism a norm in all applied postmodern Theories. This applies both in terms of how knowledge is produced, recognized, and transmitted - one cultural artifact - and in terms of how knowledge is produced, recognized, and transmitted - one cultural artifact - and in terms of moral and eithical principles - another cultural artifact.

Theme 4 - The Loss of the Individual & the Universal

Consequently to postmodern Theorists, the notion of the autonomous individual is largely a myth. The individual, like everything else, is a product of powerful discourses and culturally constructed knowledge. Equally, the concept of the universal - whether a biological universal about human nature; or an ethical universal, such as equal rights, freedoms, and opportunities for all individuals regardless of class, race, gender, or sexuality - is, at best, naive. At worst, it is merely another exercise in power-knowledge, an attempt to enforce dominant discourses on everybody. The postmodernist view largely rejects both the smallest unit of society - the individual - and the largest - humanity - and instead focus on small, local groups as the producers of knowledge, values, and discourses. Therefore, postmodernism focuses on sets of people who are understood to be positioned in the sane way - by race, sex, or class, for example - and have the same experiences and perceptions due to this positioning.

They write,89 with regard to “applied postmodernism”,

The intense focus on identity categories and identity politics means that the individual and the universal are largely devalued. While mainstream liberalism focuses on achieving universal human rights and access to opportunities, to allow each individual to fulfill their potential, applied postmodern scholarship and activism is deeply skeptical of these values and even openly hostile to them. Applied postmodedern Theory tends to regard mainstram liberalism as complacent, naive, or indifferent about the deeply ingrained prejudices, assumptions, and biases that limit and constrain people with marginalized identities. The “individual” in applied postmodernism is something like the sum total of the identity groups to which the person in question simultaneously belongs.

They expand on what they see as the 2 principles and 4 themes of postmodernism through much of the rest of the chapter.

In their chapter, 2 POSTMODERNISM’S APPLIED TURN, in the section THE POSTMODERN PRINCIPLES AND THEMES IN ACTION, they revise the 2 principles and 4 themes where needed to reflect how, in what they call applied postmodernism, these are, well, applied.

you can see more about this describee stuffs in the section “NAME” in the section on postmodernism in the CWE

Also, they state90 that rather than dying out, postmodernism, in the form of the ideas they lay out in 1 Postmodernism,

evolved and diversified into distinct strands - the cynical Theories we have to live with today - and became more goal-oriented and actionable. For this reason, we call the next wave of activism-scholarship applied postmodernism, and it is to this development we now turn our attention.

In the following chapter, 2 Postmodernism’s Applied Turn,

They write that postmodernism metastasized into social justice scholarship and activism (pages 23)

the roots of the tree that would eventually yield the nut that is CRT. They discuss the r

deconstructionism (pages 23, 45)

Beginning of CRT & the Coining of the Term

According to the editors of Critical Race Theory - the Key Writings That Formed the Movement, critical race theory emerged in the 1980s.91 However, critical race theorists Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic write92 in Critical Race Theory - an Introduction,

Critical race theory sprang up in the 1970s, as a number of lawyers, activists, and legal scholars across the country realized, more or less simultaneously, that the heady advances of the civil rights era of the 1960s had stalled and, in many respects, were being rolled back. Realizing that new theories and strategies were needed to combat the subtler forms of racism that were gaining ground, early writers, such as Derrick Bell, Alan Freeman, and Richard Delgado, put their minds to the task. They were soon joined by others, and the group held its first workshop at a convent outside Madison, Wisconsin, in the summer of 1989. Further conferences and meetings took place.

While these authors disagree whether CRT began in the 1970s or the 1980s, they agree that CRT has roots in the the critical legal studies movement in the 1970s and in the 1980s when, according to the editors of CRT - Key Writings, the term ‘critical race theory’ was coined as such by the organizers of the “Critical Race Theory Workshop” to make it clear that the field occupies the

intersection of critical theory and race, racism and the law.

Below is a Venn diagram we made to depict this intersectional description of CRT.

From Radical Feminism & Critical Legal Studies to Critical Race Theory

Delgado and Stefancic write93 in Critical Race Theory - an Introduction that,

critical race theory builds on the insights of two previous movements, critical legal studies and radical feminism, to both of which it owes a large debt. It also draws from certain European philosophers and theorists, such as Antonio Gramsci, Michael Foucault, and Jacques Derrida, as well as from the American radical tradition exemplified by such figures as Sojourner Truth, Frederick Douglas, W. E. B. Du Bois, Cesar Chavez, Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Black Power and Chicano movements of the sixties and early seventies. From critical legal studies, the group borrowed the idea of legal indeterminacy - the idea that not every legal case has one correct outcome. . .

The group also built on feminism’s insights into the relationship between power and the construction of social roles, as well as the unseen, largely invisible collection of patterns and habits that make up patriarchy and other types of domination. From conventional civil rights thought, the movement took a concern for redressing historical wrongs, as well as the insistence that legal and social theory lead to practical consequences. CRT also shared with it a sympathetic understanding of notions of community and group empowerment. From ethnic studies, it took notions such as cultural nationalism, group cohesion, and the need to develop ideas and texts centered around each group and its situation.

In Critical Theory - the Key Concepts, Felluga wrote94 that some

third-wave feminists fault past thinkers for not taking into consideration issues of race since women from certain racial groups are doubly disadvantaged in contemporary culture. This has led to the rise of Black Feminism, particularly Critical Race Theory (see intesectionality, Matrix of Domination, whiteness as property).

In the book CRT - Key Writings, there is much regarding the emergence of critical race theory from critical legal studies. Some of it pertains to the tension95 and separation of these 2 branches of critical theory. Most of this is contained in the 4 essays in Part 2. Critical Race Theory and Critical Legal Studies: Contestation and Coalition.96 It would, however, be too esoteric here and sidetrack us needlessly.

CRT’s Marxism

Author Dino Franco Felluga97 writes in Critical Theory - the Key Concepts.98 that CRT is a

critical school

that

developed out of and largely superseded Critical Legal Studies (CLS)

Felluga also wrote,99

Although Critical Race Theory (CRT) started as an offshoot of CLS, it has largely eclipsed that school of thought and has become the dominant way of approaching such legal questions.

Furthermore,100

CLS, which was an active school of critical theory in the 1970s and 1980s applied poststructuralist and Marxist strategies to critique legal institutions, questioning the extent to which one can separate law and politics while illustrating the ways that the legal system is designed to support the dominant class at the expense of marginalized, subaltern groups.

The introduction of Critical Race Theory - the Key Writings That Formed the Movement, written by key figures in CRT (see the Appendix), discusses the emergence of critical race theory from critical legal studies (CLS) in the 1980s.101 They write102 about CLS that

a predominantly white left emerged on the law school scene in the late seventies, a development which played a central role in the genesis of Critical Race Theory. Organized by a collection of neo-Marxist intellectuals, former New Left activists, ex-counter-culturalists, and other varieties of oppositionists in law schools, the Conference on Legal Studies established itself as a network of openly leftist law teachers, students, and practitioners committed to exposing and challenged the ways American law served to legitimize an oppressive social order.

CRT’s Anti-Liberal Past & Present

The editors of CRT - Key Writings immediately continue,103

Like the later experience of Critical Race writers vis-a-vis race scholarship, “crits” found themselves frustrated with the presuppositions of the conventional scholarly legal discourse: they opposed not only conservative legal work but also the dominant liberal varieties. Crits contended that liberal and conservative legal scholarship operated in the narrow ideological channel within which law was understood as qualitatively different from politics. The faith of liberal lawyers in the gradual reform of American law through the victory of superior rationality of progressive ideas depended on a belief in the central ideological myth of the law/politics distinction, namely, that legal institutions employ a rational, apolitical, and neutral discourse with which to mediate the exercise of social power. This, in essence, is the role of law as understood by liberal political theory. Yet politics was embedded in the very doctrinal categories with which law organized and represented social reality.

The term “crit” used in the quote above is later104 defined (along with alternate term “CLSer”) to refer to attendees of the Conference of Critical Legal Studies (founded 1976) who are

a group of law teachers, students, and some practitioners (“crits,” “CLSers”), who are loosely organized as leftist intellectuals and activists

Critical Theory - the Key Concepts105

CRT is careful to distinguish its goals from those of liberal civil rights scholarship and activism. Although it takes inspiration from earlier civil rights agitation, the practitioners of CRT “take racial power of color are concentrated but also in the institutions where their position is normalized and given legitimation” (Crenshaw et al. 1995: xxii). Critiquing the liberal view that law is separate from politics became of its purported adherence to neutral and apolitical rational debate, CRT argues that the problem lies with the law itself is conceived. The goal, then, is not just to change the law, as in the civil rights movement, but also to uncover “how law was a constitutive element of race itself: in other words, how law constructed race” (xxv).

The Alternative Course

In Critical Race Theory - The Key Writings That Formed the Movement, the editors write,106

two key institutional events in the development of Critical Race Theory as a movement.

The first is the student protest, boycott, and organization of an alternative course on race and law at Harvard Law School in 1981 - an event that highlights the significance of Derrick Bell and the Critical Legal Studies movement to the ultimate development of Critical Race Theory, and symbolizes Critical Race Theory’s oppositional posture vis-a-vis the liberal mainstream.