Political Compass, Political Spectrums, Horseshoe Theory, Double Horseshoe Theory (Figure 8), Political Triangle & More

there's more than just left vs right

Last updated November 26, 2024.

“…clearly they cannot both be true as long as we restrict ourselves to a one-dimensional system. They could easily be reconciled if we accepted a two-dimensional system…”

~ Dr. Eysenck in The Psychology of Politics, 1954

CONTENTS

The 1 Dimensional Political Spectrums

William James’ 1 Dimensional Political Spectrum - Tender-Minded (Introvert) to Tough-Minded (Extrovert)

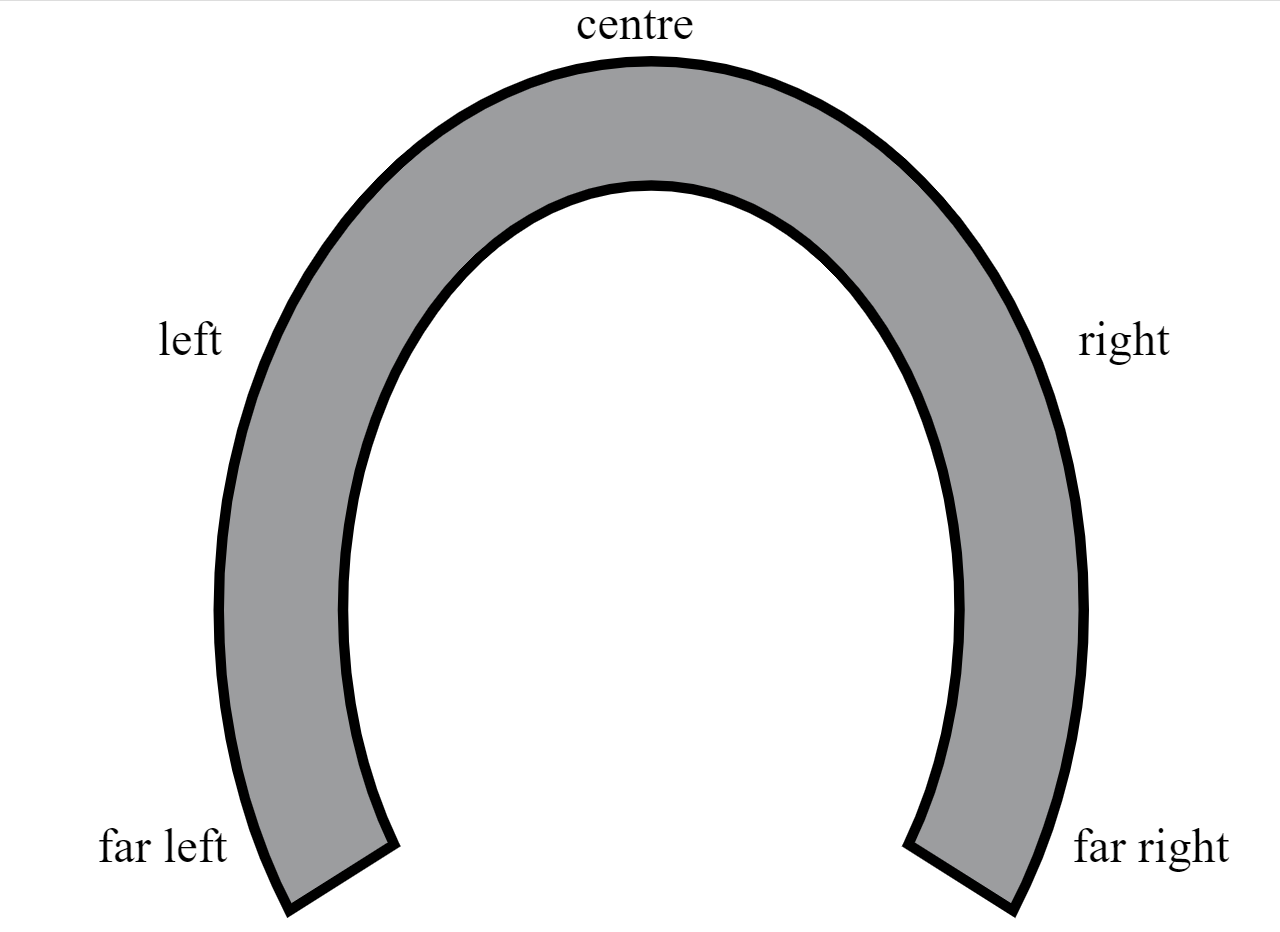

The 1 Dimensional Horseshoe Model or Centrist/Extremist Model

2 Dimensional Political Maps

The Hans Eysenck Model

The L.W. Ferguson Model

The Bryson and McDill Model

The L.F.E. Theory of the Political Spectrum

The Nolan Model

The Kitschelt Model

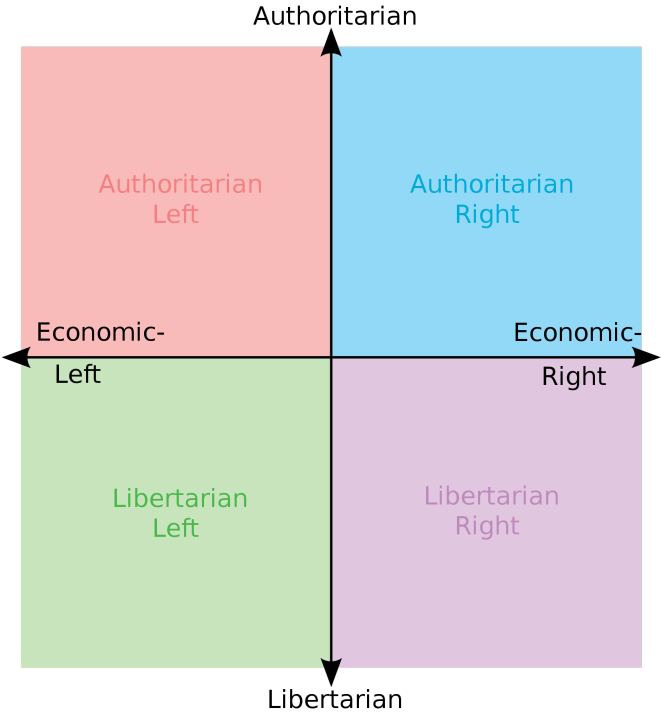

The Political Compass

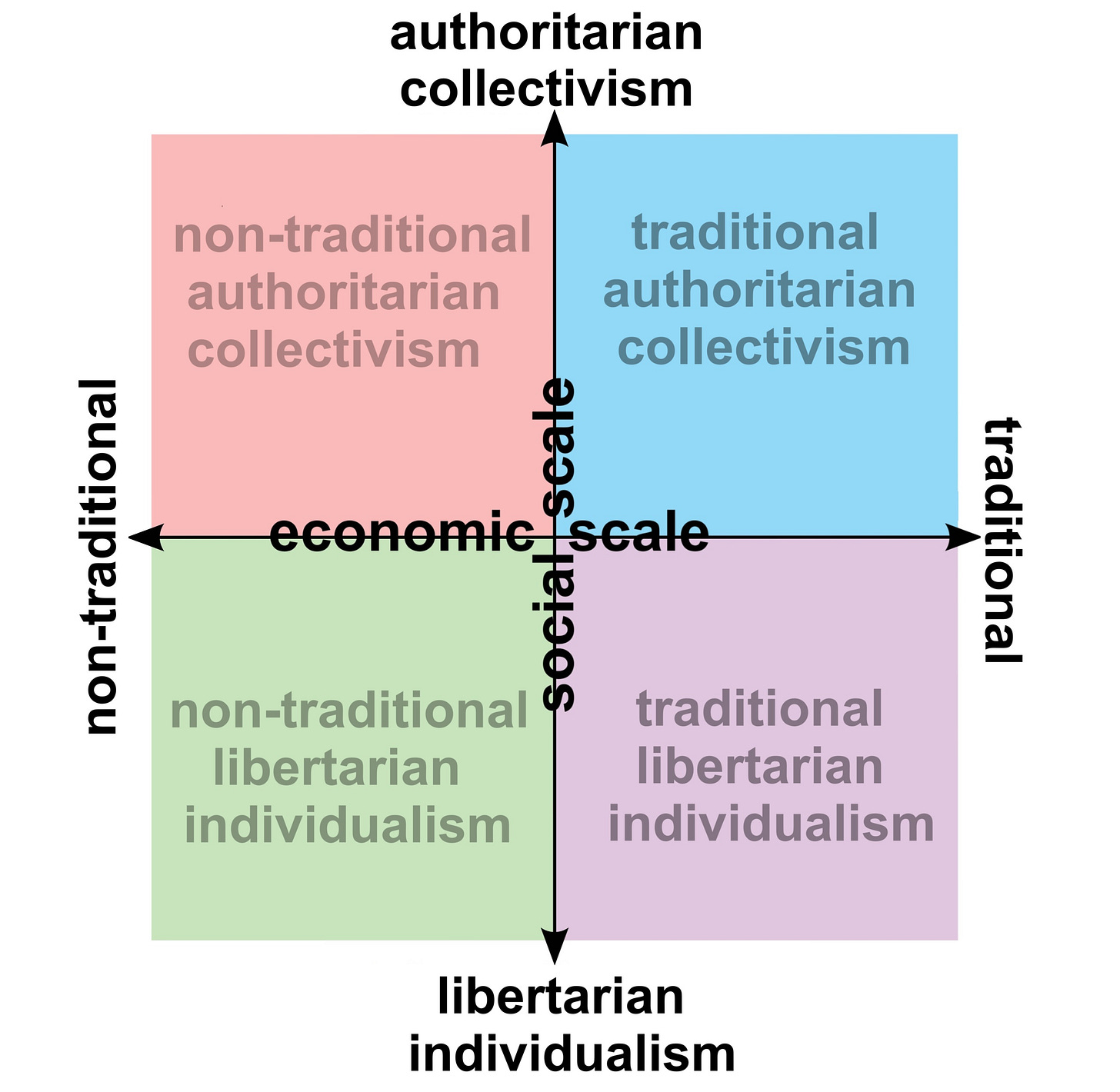

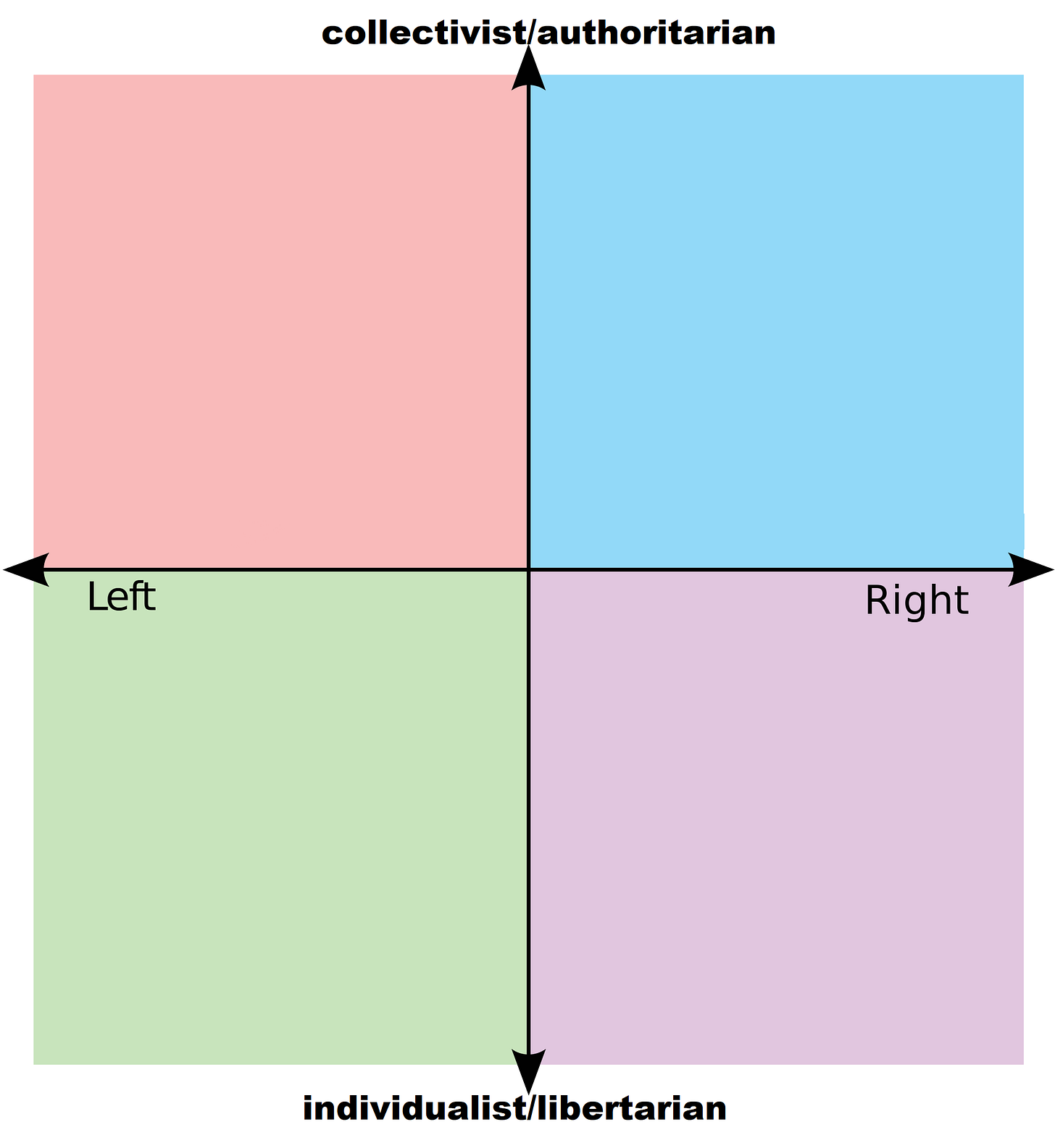

Our Individualist/Libertarian vs Collectivist/Authoritarian Modification to the Political Compass

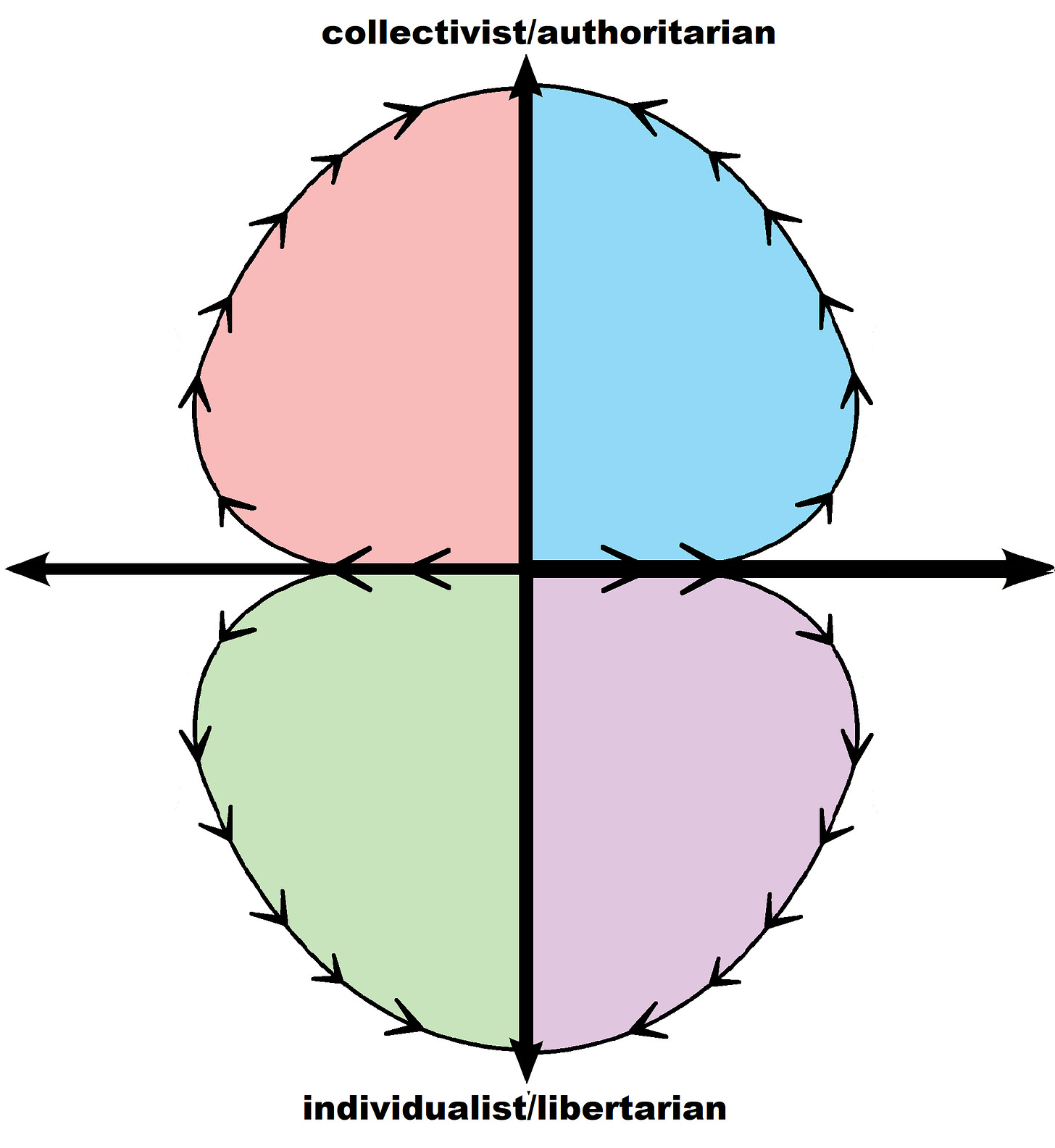

Our Double Horseshoe Modification to the Political Compass

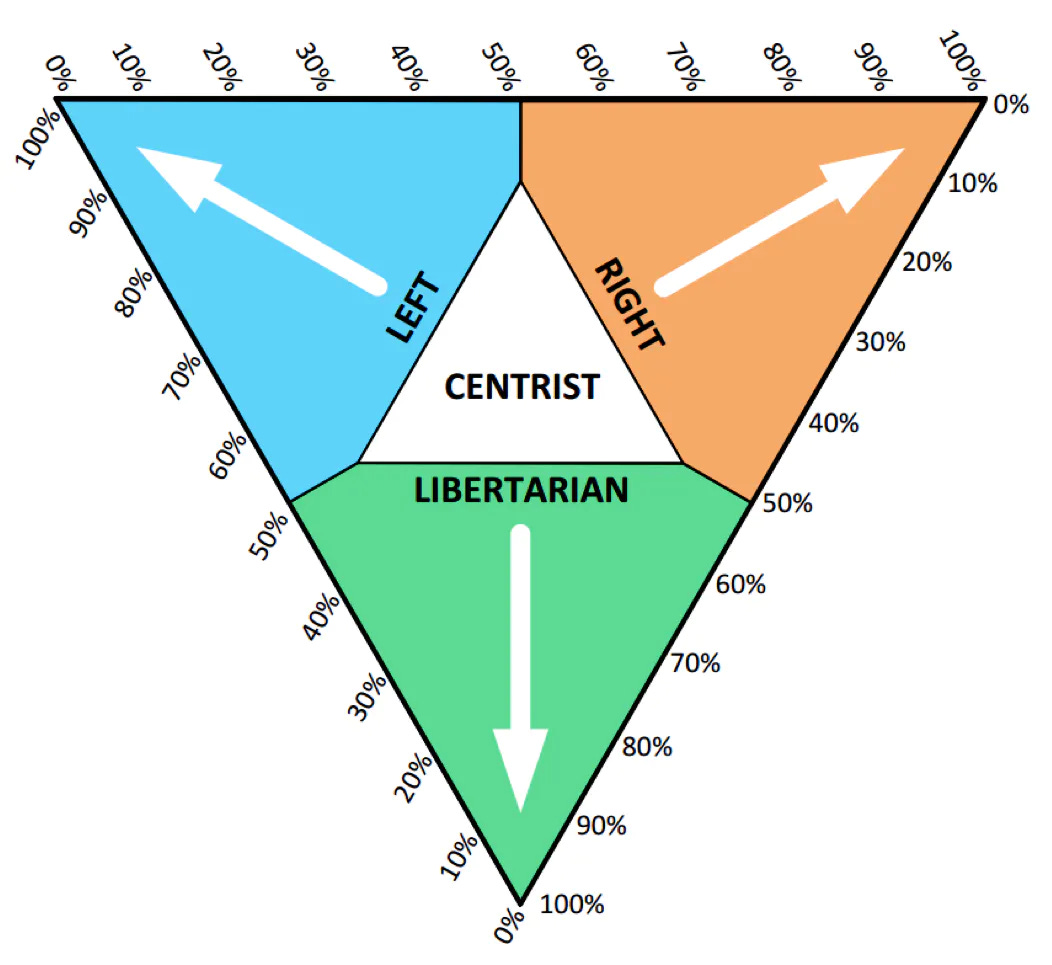

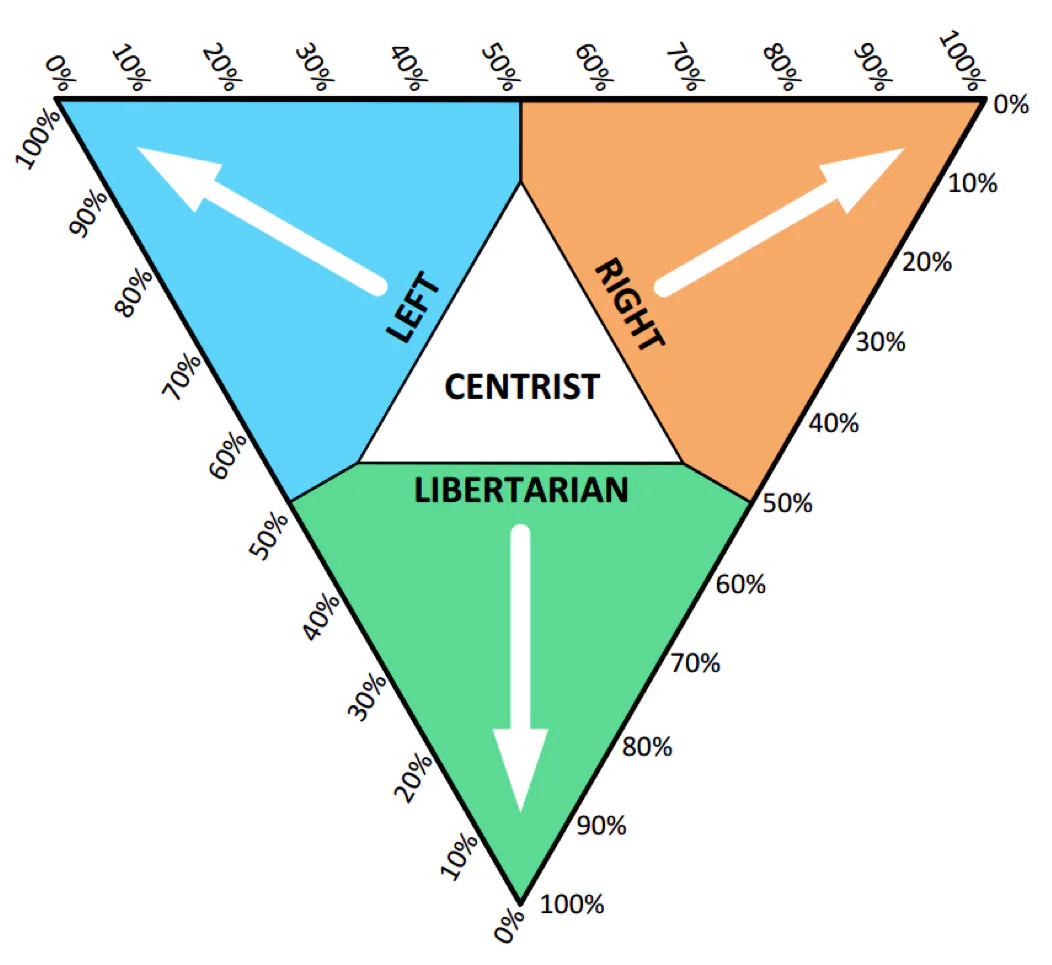

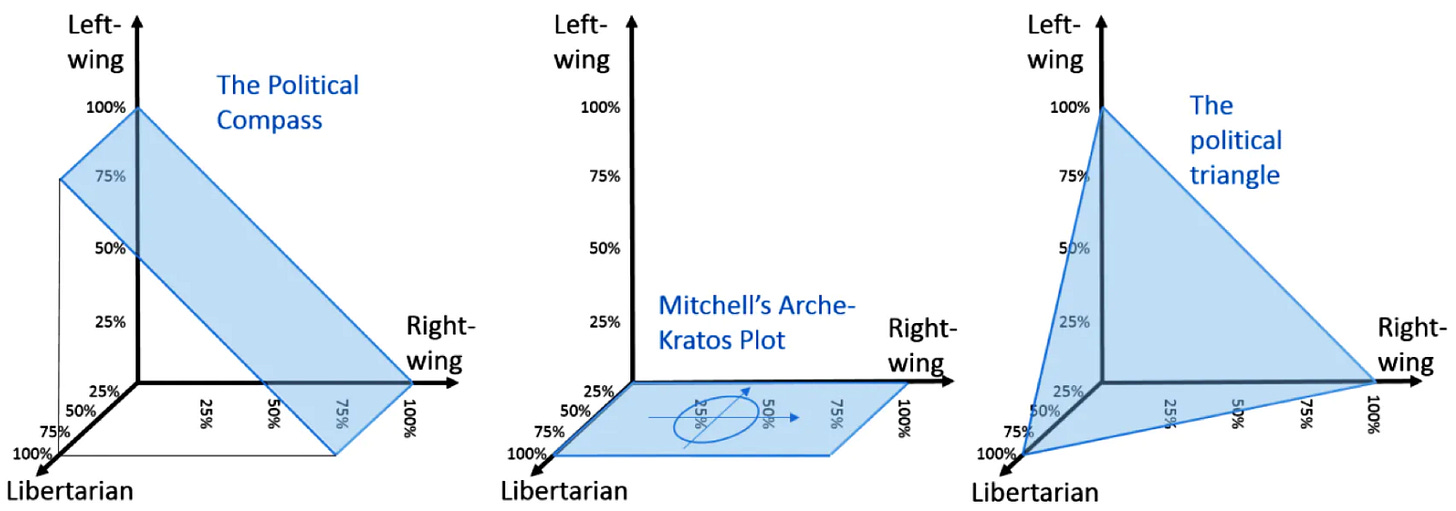

The 3 Dimensional Political Triangle of Nick Kastelein

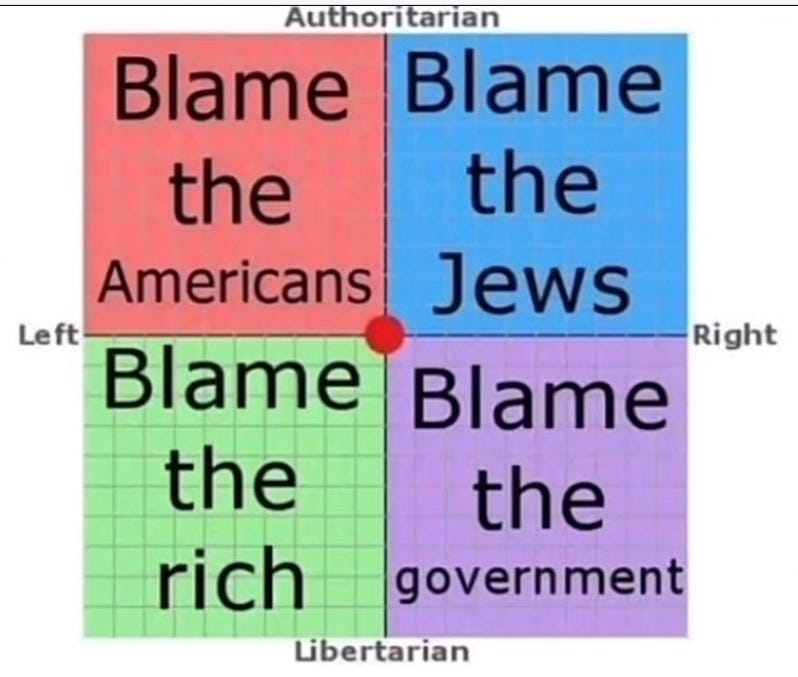

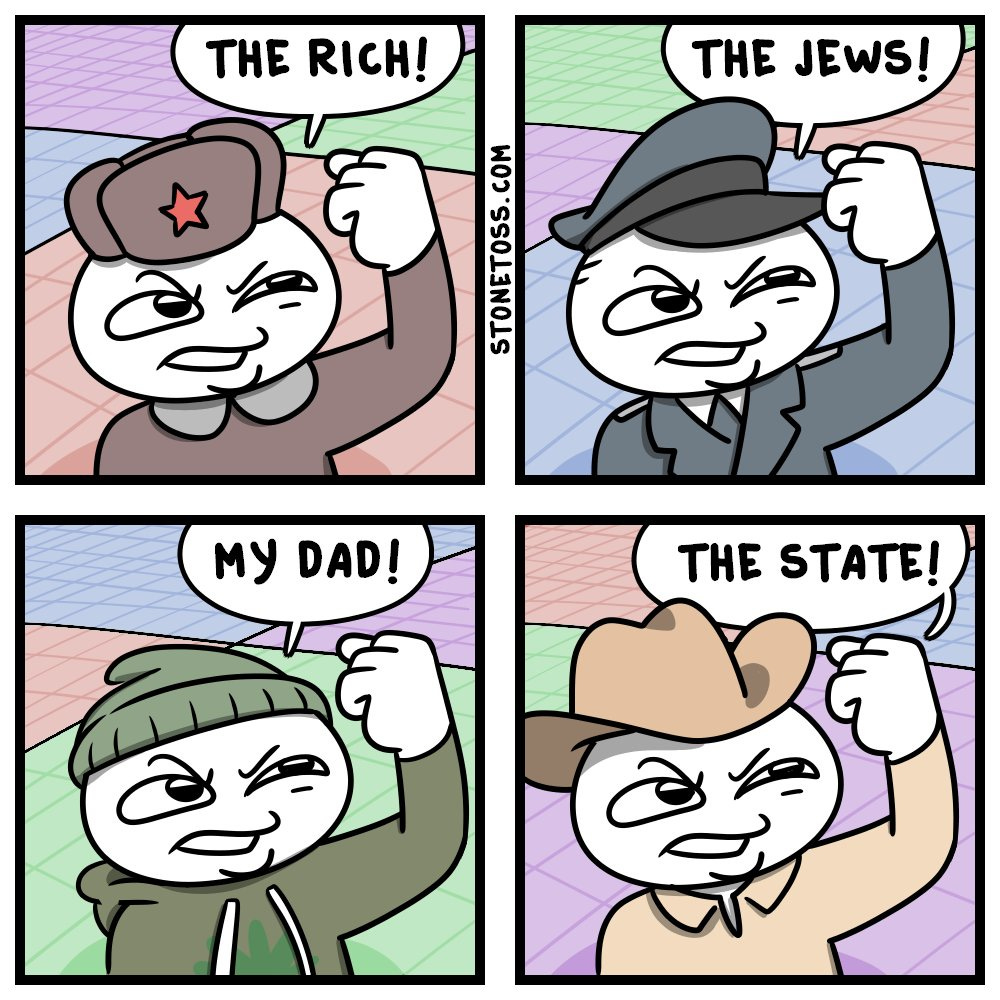

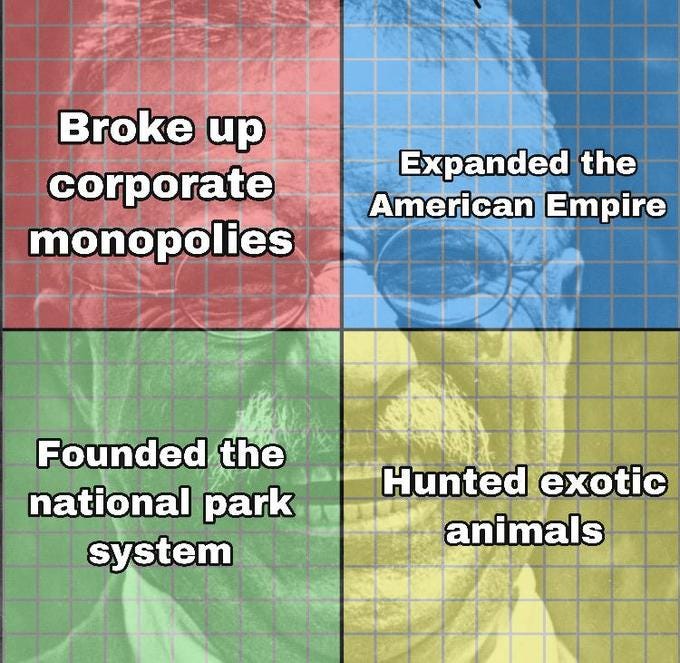

Memes

Also See

Footnotes

1 Dimensional Political Spectrums

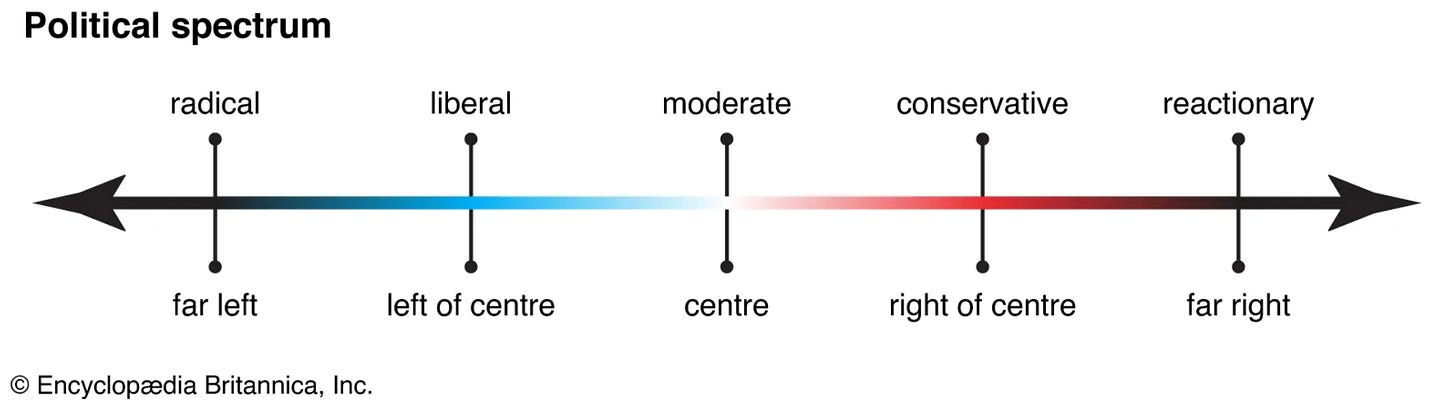

When it comes to politics, perhaps most people think in terms of left vs right. This is sometimes called the political spectrum (by Britannica, Harvard and Khan Academy for examples) and at times called the ideological spectrum (by Stanford University and Pew Research Center for examples).

We will go further into the political spectrum / ideological spectrum in it’s own section of the Culture War Encyclopedia. For our purpose here, know that the political spectrum / ideological spectrum has been referred to as

the old-fashioned left-right linear model

and that, as we’ll see, starting in at least the mid 1900’s, some have found it more useful to map political opinions on more than one dimension. For example, in a book printed in 1954, the following 1 dimensional models are used as part of a suggestion that such models are inadequate and that 2 dimensional models (like the political compass) are more useful.

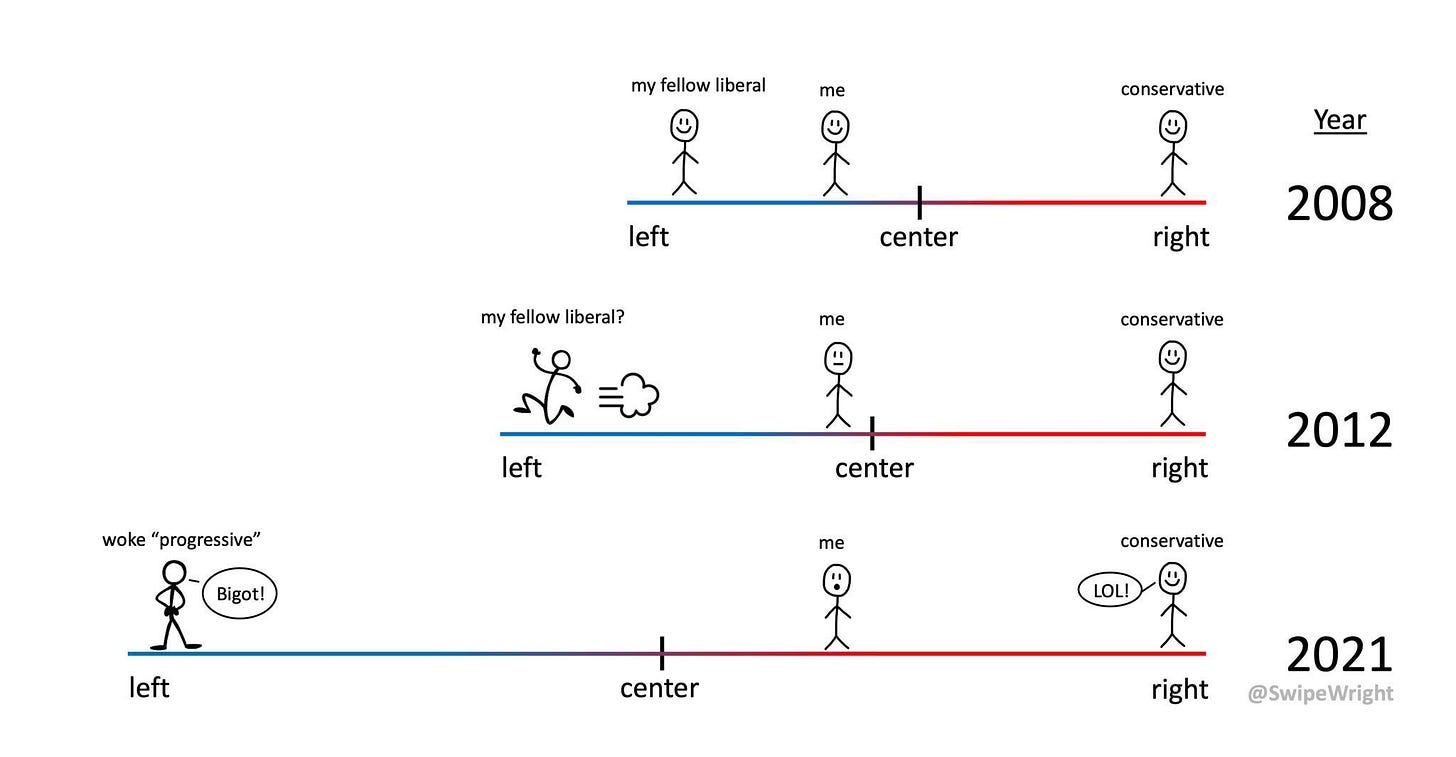

We will return to that below. Before we move on, enjoy this meme from @SwipeWright...

William James’ 1 Dimensional Political Spectrum - Tender-Minded (Introvert) to Tough-Minded (Extrovert)

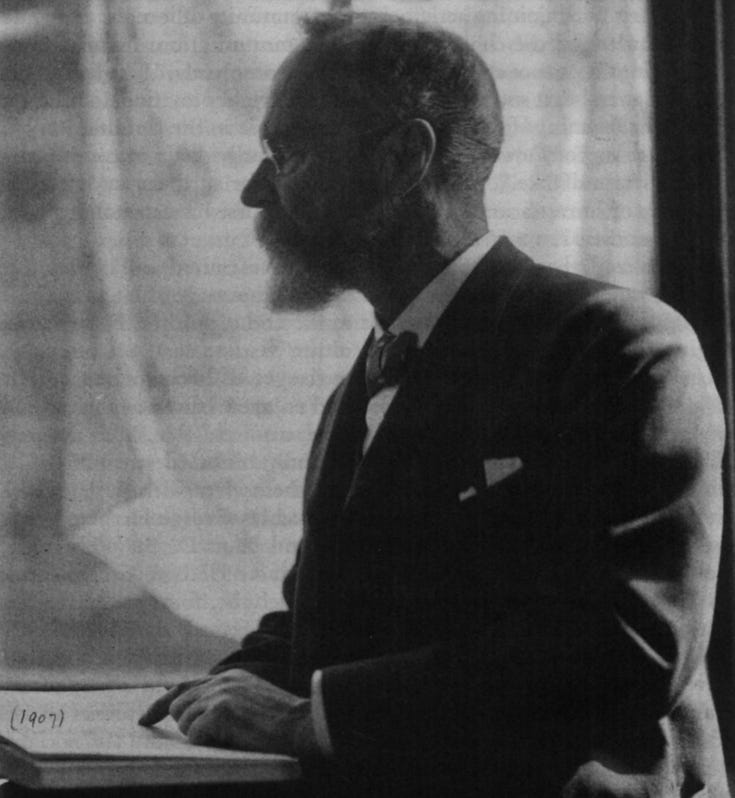

William James (1842-1910) was an American psychologist, philosopher, founder of functionalism in psychology, leader of pragmatism in philosophy (according to Britannica), author of The Principles of Psychology with Henry Holt (1890), The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902) and many other works (according to Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy).

William James’ Pragmatism: A New Name for Some Old Ways of Thinking was published in 1907. According to Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy,

James classifies philosophers according to their temperaments: in this case “tough-minded” or “tender-minded.” The pragmatist is the mediator between these extremes, someone, like James himself, with “scientific loyalty to facts,” but also “the old confidence in human values and the resultant spontaneity, whether of the religious or romantic type” (P 17).

Under Lecture I of his book, he writes of 2 different kinds of “mental make-up” each with their own set of traits. He writes,

I will write these traits down in two columns. I think you will practically recognize the two types of mental make-up that I mean if I head the columns by the titles 'tender-minded' and 'tough-minded' respectively.

THE TENDER-MINDED

Rationalistic (going by 'principles'), Intellectualistic, Idealistic, Optimistic, Religious, Free-willist, Monistic, Dogmatical.

THE TOUGH-MINDED

Empiricist (going by 'facts'), Sensationalistic, Materialistic, Pessimistic, Irreligious, Fatalistic, Pluralistic, Sceptical.

Later, we will see psychologist Hans Eysenck suggest that James’ tender-minded person would be an introvert and his tough-minded person would be an extrovert if we were to use the introvert/extrovert spectrum.

A bit further on, W. James writes,

Each of you probably knows some well-marked example of each type, and you know what each example thinks of the example on the other side of the line. They have a low opinion of each other. Their antagonism, whenever as individuals their temperaments have been intense, has formed in all ages a part of the philosophic atmosphere of the time. It forms a part of the philosophic atmosphere to-day. The tough think of the tender as sentimentalists and soft-heads. The tender feel the tough to be unrefined, callous, or brutal.

Of course, William James’ model is about psychology not politics. However, Hans Eysenck brings it into his Psychology of Politics (1954) as we’ll see.

The 1 Dimensional Horseshoe Model or Centrist/Extremist Model

An early expression of what we now call ‘horseshoe theory’ of ‘horseshoe model’ can be found in “The Lands of the Saracen” by Bayard Taylor (1854) where he describes witnessing a French monarchist (who some might think of as far-right) and a French socialist (who some may think of as far-left) agreeing that Great Britain’s legislation is perfidious which caused him to blurt out, “This is where the extremes meet!”1

In other words, though they are on opposite ends of the political spectrum, they agreed with each other’s political view point, at least on the subject of Great Britain’s legislation.

Wikipedia claims that the horseshoe theory

is attributed to the French philosopher and writer of fiction and poetry Jean-Pierre Faye in his 1972 book Théorie du récit: introduction aux langages totalitaires, in relation to Otto Strasser.

Wikipedia, however, is not itself a valid source. It is a place where people can claim things and then ideally provide valid and sufficient evidence to support those claims. They do not always do so. For the claim that horseshoe theory is attributed to Faye in his 1972 book Théorie du récit: introduction aux langages totalitaires, they provide the footnote

Faye, Jean Pierre (1972). Théorie du récit: introduction aux langages totalitaires. Critique de la raison, l'économie narrative [Narrative theory: introduction to totalitarian languages. Critique of reason, narrative economy.]. Collection Savoir (in French). Paris: Hermann. p. 124. ISBN 978-2-7056-5695-9.

If one clicks on the link to the book, one is allowed to see only the front and back covers and the inside front cover. There is no way that I can find to confirm this claim.

I found “Horseshoe Theory in American Politics” written by Rachel Sobers, published by Vanderbilt Political Review November 11, 2024 in author Rachel Sobers writes that horseshoe theory is

attributed to French author and philosopher Jean-Pierre Faye

For this claim, she cites “Rallying the Radicals: What do the Radical Left and the Radical Right have in Common?” wherein it states

so-called horseshoe theory

is

attributed to the French writer Jean-Pierre Faye

There is, however, no source given.

Los Angeles Times columnist Jonah Goldberg writes in “Column: 2023 was the year I started believing in the horseshoe theory of politics” (December 26, 2023) that the term horseshoe theory

is often attributed to French author Jean-Pierre Faye‘s 1996 book “Le Siècle des ideologies” (“The Century of Ideologies”),

The link in the quote above links to a Wikipedia page on Jean-Pierre Faye that links to other sources that, like this LA Times piece, state that it is attributed to Faye and link to other sources that state the same thing that link to other sources that state the same thing that link to other sources that state the same thing that link to other sources that state the same thing that…you get the idea.

Leaving the issue of who came up with it, how applicable is it?

Consider this: would you call a Christian cowboy who lives on a ranch, who just wants to be left alone to run his ranch and who has no interest in suppressing human rights and who does not want the government or anyone else to suppress human rights a right winger? Probably. How about a person who thinks that a Christian theocracy should rule over people and prevent them from engaging in premarital sex, from drinking and who thinks the government should make people go to church and read the Bible? Right wing? Is not the hypothetical cowboy quite opposite from the hypothetical Christian theocratic person on the issue of freedom vs authoritarianism? One wants freedom and the other wants an authoritarian control that prevents freedom. Does it make sense to place both of these people on the same side of a spectrum?

Consider the following 2 hypothetical people: One is a Wiccan astrologer and crystal healer who has a little plot of land with a small house, some chickens, a cow, a marijuana field and who just wants to live and let live. The other is an atheist and a communist who thinks we should have a strong authoritarian government in order to seize the means of production and to collectivize all resources to ensure equity. Are these people both on the same left side of the spectrum?

In some senses the left wing communist authoritarian is more like the right wing theocratic authoritarian than the left wing Wiccan anti-authoritarian. The cowboy has more in common with the Wiccan than either has with the authoritarians. When thought of in this manner, both the straight lined political spectrum and the horseshoe model seem inadequate.

Let us therefore think outside the line and explore some 2 dimensional models. Be sure to see my double horseshoe model below.

2 Dimensional Political Maps

The Hans Eysenck Model

Picture William James’ tender-mindedness to tough-mindedness spectrum represented as a vertical line. Now lay that vertical line on top of a horizontal line running from (literally and figuratively) left to right representing the 1 dimensional political spectrum. One dimension plus an other dimension at 90 degrees (horizontal plus vertical) equals a 2 dimensional plane.

You may remember from your math classes the Cartesian plane, also called the coordinate grid or graph, of the Cartesian coordinate system with the x axis and y axis and the 4 quadrants.

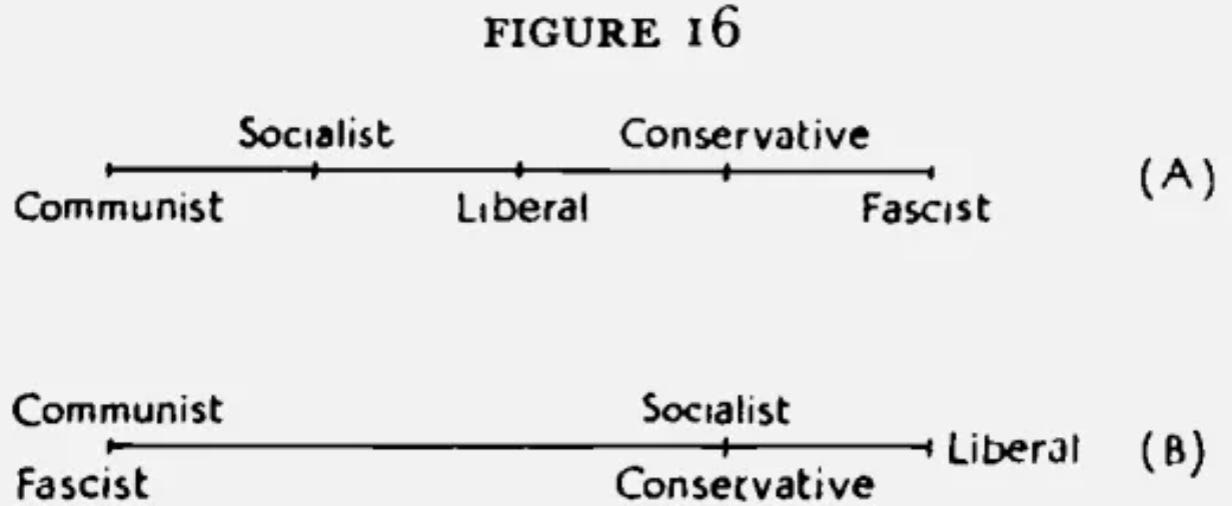

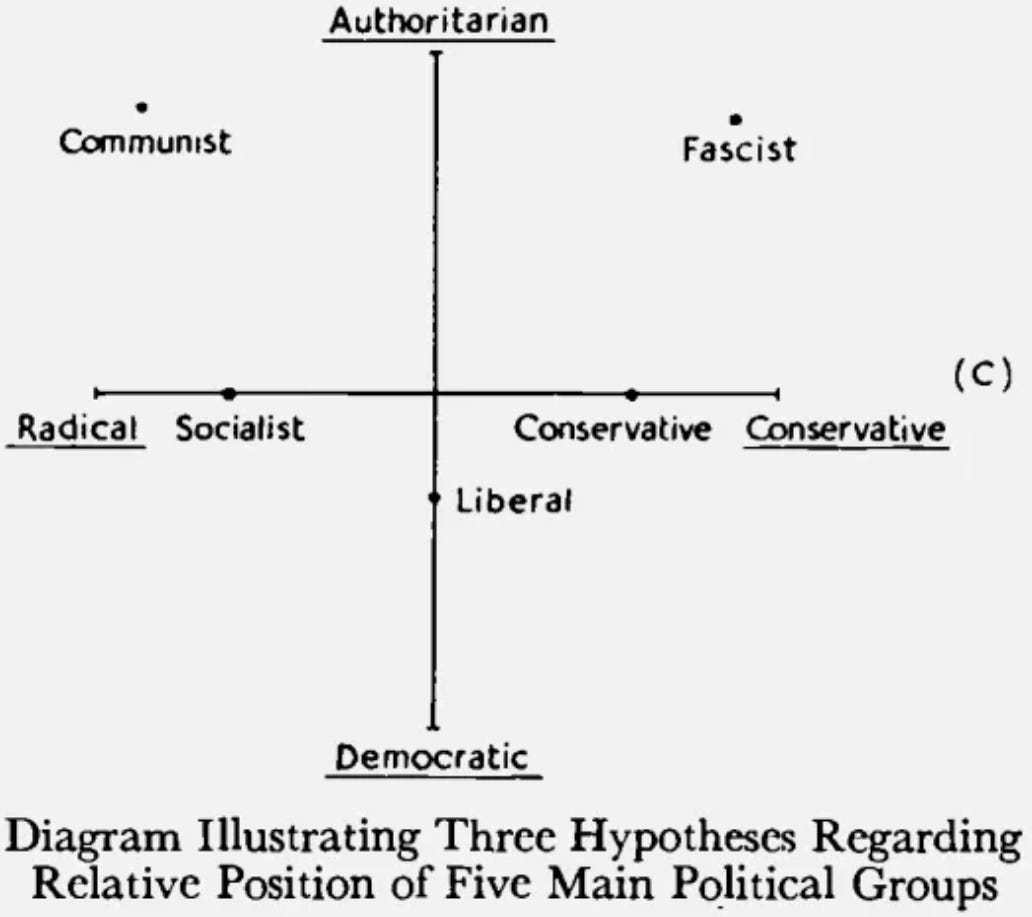

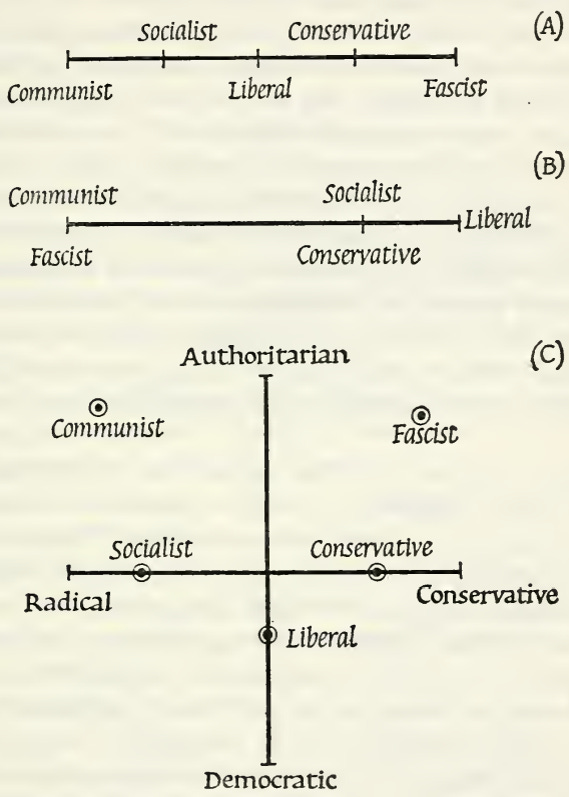

Hans Eysenck was a Ph.D. (according to his book), a British psychologist (according to Britannica) and a professor (according to the NY Times). Consider figure 16 A, B and C (shown below) from his book The Psychology of Politics (page 111), published in 1954, about which he writes (starting on page 109),

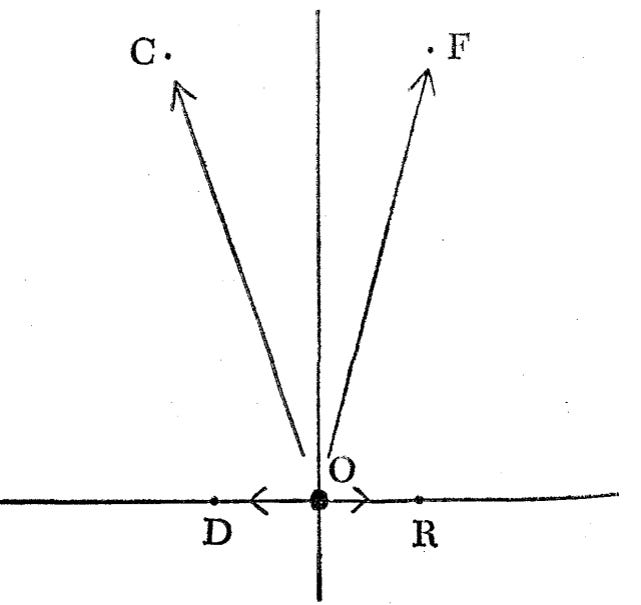

It is often said that in the political spectrum Socialists are to the left of Liberals, Liberals to the left of Conservatives, with Communists and Fascists, respectively, constituting the extreme left and the extreme right. In terms of dimensions, therefore, we might represent the position somewhat as in Figure 16 A, with one dimension being thought sufficient to represent political parties.

On the other hand, it is also sometimes said that there is a considerable similarity between Fascists and Communists; so much so, indeed, that there is very little to choose between them. Both, on this reckoning, are opposed to the democratic parties, i.e. the Socialist, Conservative, and Liberal parties, and some observers (usually Liberals) would add that both the Conservatives and Socialist parties have advanced some way towards the Communist-Fascist outlook, leaving the Liberals, as it were, at the other end of this continuum, which might therefore look something like that indicated in Figure 16 B.

Much might be said in favour of both these hypotheses, but clearly they cannot both be true as long as we restrict ourselves to a one-dimensional system. They could easily be reconciled if we accepted a two-dimensional system, as illustrated in Figure 16c, where our abscissa represents our left-right continuum, and our ordinate represents our democratic versus autocratic continuum, as we may provisionally call it.

Eysenck offers this (page 111)…

He places Authoritarian opposite of Democratic. We note this because, as we’ll see, today’s political compass places Authoritarian opposite of Libertarian. On page 130 we have the following…

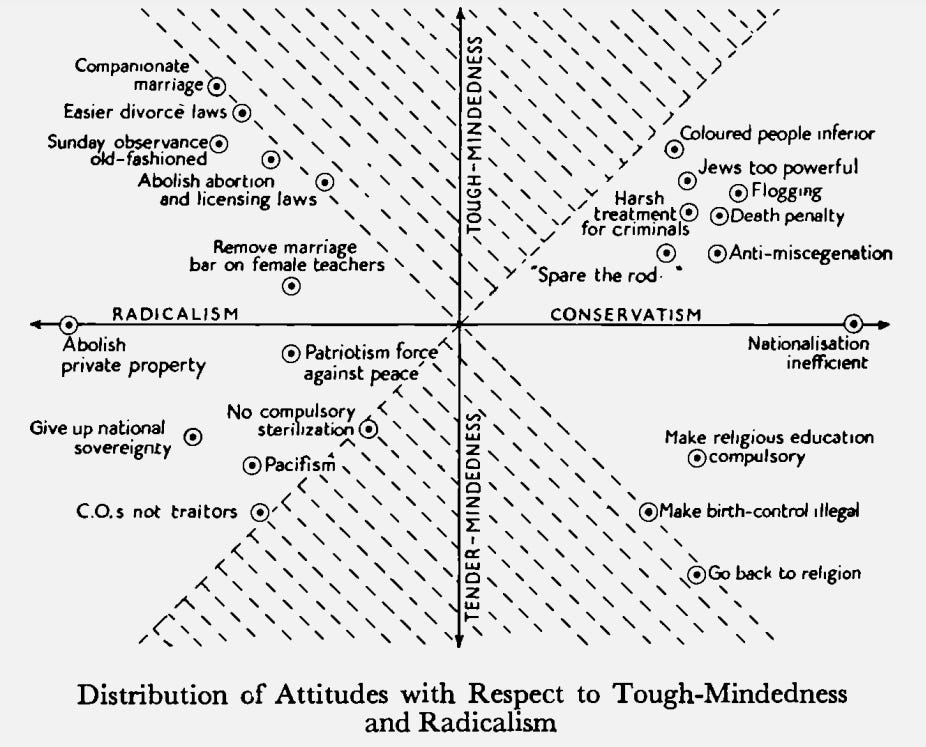

Now we see the tender-minded to tough-minded spectrum, which Hans Eysenck acknowledges he borrowed from William James, as a vertical line on a horizontal line that more or less represents a spectrum ranging from political radicalism to political conservatism. This welds William James’ psychological spectrum to a political spectrum at a right angle creating a plane with 4 quadrants. It is on pages 130 to 132 where Eysenck explains that he borrowed the tender-mindedness/tough-mindedness factor from

a book by W. James, where he refers to two opposed types of temperament leading to opposed philosophical beliefs as the ‘tender-minded’ and the ‘tough-minded’ respectively. As we shall make much use of this dichotomy, a brief quotation from James will make its meaning clearer. James starts his discussion on pragmatism by pointing out that philosophical systems are often influenced or determined by the temperament of their authors. He goes on to say that ‘the particular difference of temperament that I have in mind ... is one that has counted in literature, art, government, and manners as well as in philosophy. In manners we find formalists and free-and easy persons. In government, authoritarians and anarchists. In literature, purists or academicals, and realists. In art, classics and romantics. You recognize these contrasts as familiar; well, in philosophy we have a very similar contrast expressed in the pair of terms ‘rationalist’ and ‘“‘empiricist’’, ‘“empiricist’’? meaning your lover of facts in all their crude variety, “‘rationalist’? meaning your devotee to abstract and eternal principles.’ James then goes on to a brief discussion of some of these differences and finally gives a table of these: ‘I will write these traits down in two columns. I think you will practically recognize the two types of mental-make up that I mean if I head the columns by the titles ‘‘tender-minded”’ and “‘tough-minded” respectively…

Eysenck then provides the following that we saw above from William James, word-for-word,

THE TENDER-MINDED

Rationalistic (going by 'principles'), Intellectualistic, Idealistic, Optimistic, Religious, Free-willist, Monistic, Dogmatical.

THE TOUGH-MINDED

Empiricist (going by 'facts'), Sensationalistic, Materialistic, Pessimistic, Irreligious, Fatalistic, Pluralistic, Sceptical.

Eysenck then writes,

We may perhaps accept for the time being James’s term and call this dimension tender-mindedness versus tough-mindedness, or, more simply, the T-factor. The intrinsic meaningfulness of this factor will become more apparent as we discuss further evidence; for the moment let us merely note that the tender-minded set of opinions appears to be dominated by ethical, moralistic, super-ego, altruistic values, while the tough-minded set of opinions is dominated by realistic, worldly, egotistic values, and it may be noted that Koestler’s book, The Yogi and the Commissar, seems to drive at much the same division as indicated by this factor, a division which clearly cuts across party lines. On the left we have the ‘tenderminded’ (Lansbury, I.L.P., the Pacifist group, the religious leftists, etc.) as well as the ‘tough-minded’ (Communists, Trotskyites, etc.). Similarly, on the right there are the ‘tender-minded’ religious groups as well as the ‘tough-minded’ semi-fascist combinations. Indeed, in practice this division is well recognized by parties of the right as well as of the left, but no term has been suggested to point out what is common to the adherents of either the ‘tough’ or the ‘tender’ line in both parties.

Later, on pages 174 and 175, Eysenck writes,

We shall suggest that ‘tough-mindedness’ is a projection on to the field of social attitudes of the extraverted personality type, while ‘tender-mindedness’ is a projection of the introverted personality type. Before turning to a proof of this hypothesis let us first briefly discuss this concept of extraversion-introversion. Unfortunately these terms have been used so widely by non-psychological writers and by the man in the street that they have lost almost entirely the meaning which they originally carried, and to which we must revert here. The terms extravert and introvert were used by the psychiatrist Jung to refer to two types of personality which are antithetical to each other and which had in essence been described by several other writers before him, notably by the English psychologist Furneaux Jordan and by the Austrian psychiatrist Otto Gross.

Jordan had posited an antithesis between the reflective and the active type of person; he went on to point out that the reflective type tended to be more emotional, the active type less emotional. Gross added to this hypothesis a physiological theory of how this distinction might have come about. It was not however until Jung popularized and extended these concepts that they were really widely accepted among psychologists.

Jung states very extensively all the personality traits which characterize the introvert and the extravert respectively; they all derive from the fundamental fact that the extravert has turned his interests and his instinctual energies outwards, i.e. towards the world of objective reality, while the introvert has turned his interests and his instinctual energies inwards, i.e. towards himself. ‘Quite generally one might characterize the introvert point of view by pointing to the constant subjection of the object and objective reality to the ego and the subjective psychological process ... according to the extraverted point of view the subject is considered as inferior to the object; the importance of the subjective aspect is only secondary.’ Apart from this fundamental distinction the extravert emerges as a person who values the outer world both in its material and in its immaterial aspects (possessions, riches, power, prestige), he shows outward physical activity while the introvert’s activity is mainly in the mental, intellectual sphere. The extravert is changeable and his emotions are easily aroused, but never very deeply; he is relatively insensitive, impressionable, experimental, materialistic and tough-minded.

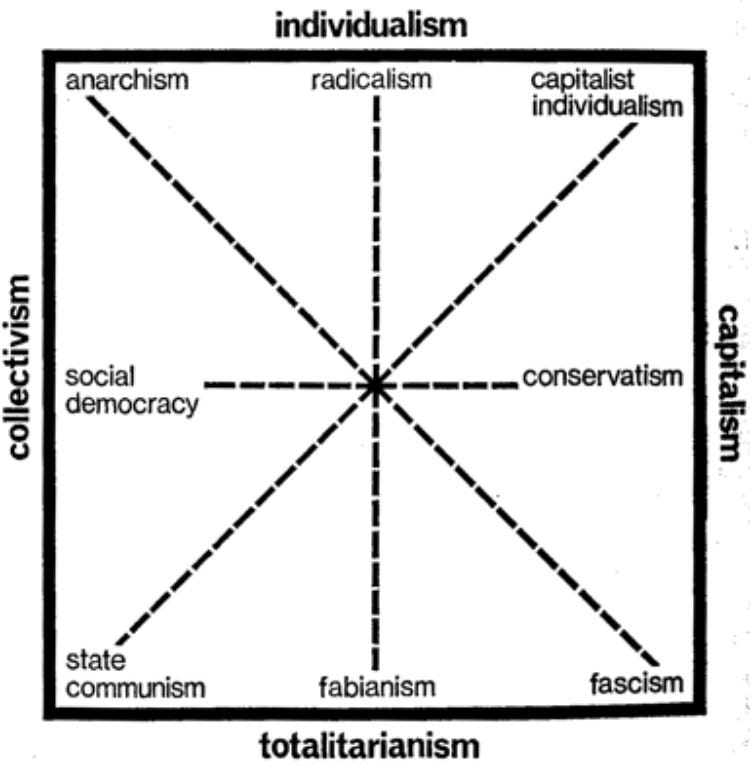

The L.W. Ferguson Model

On page 147 of The Psychology of Politics, the Hans Eysenck shows (according to him) the system of L.W. Ferguson.

The Eysenck writes (pages 145 to 147) that L.W. Ferguson

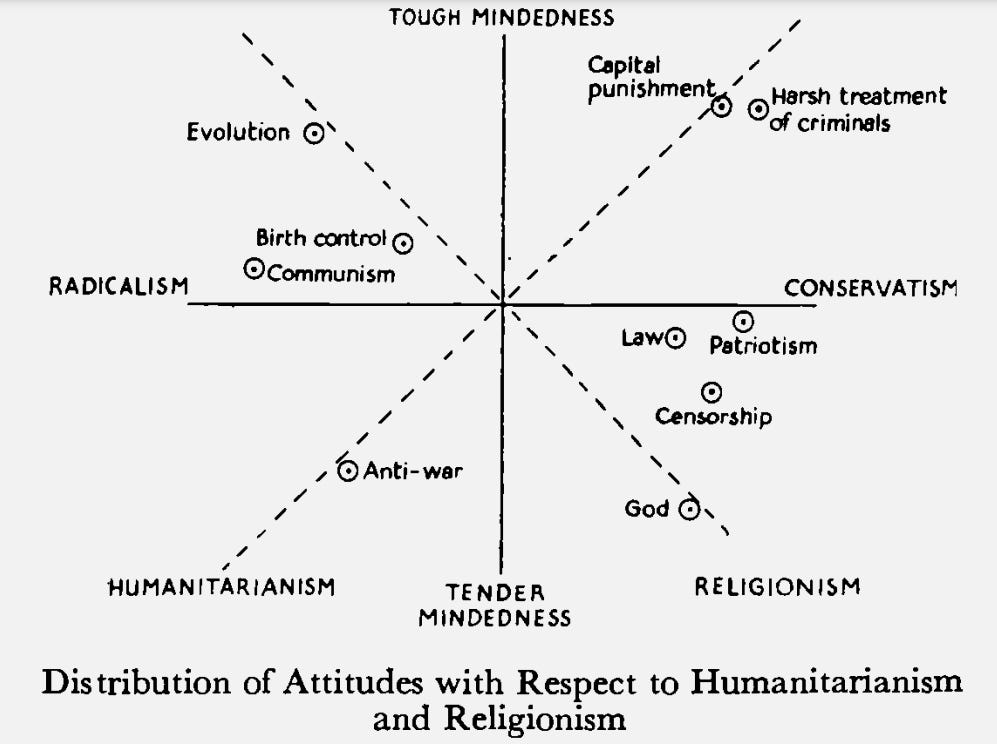

has made a determined effort in a large number of research papers to solve the problem of structure in the attitude field. He used ten carefully constructed scales dealing with evolution, birth control, God, capital punishment, treatment of criminals war, censorship, communism, law, and patriotism, which he administered to various groups of students. We shall not follow the whole course of his very extensive and careful work, in which he showed that his original results could be duplicated on different populations and at different times, but will instead reserve consideration to the main outcome of his analysis. This is shown in Figure 27.*

(* The actual analysis on which Figure 27 is based was carried out by the writer on the basis of figures published by Ferguson. This was necessary as Ferguson has never published the full results of an analysis of all ten measures.)

It will be seen that he also finds two main factors in his analysis and that the positions of the various attitude scales in this two dimensional universe are practically identical with those found in our own work. Attitudes favouring capital punishment and the harsh treatment of criminals are found in the toughminded Conservative quadrant; attitudes favourable to evolution, Communism, and birth control are found in the tough-minded Radical quadrant, anti-war attitudes in the tender-minded Radical quadrant, and attitudes favourable to God, censorship, and the law, in the tender-minded Conservative quadrant. Patriotism appears to lie almost exactly on the Radical-Conservative axis itself. In so far as there is overlap between these attitudes and those measured in our own work, agreement is almost complete.

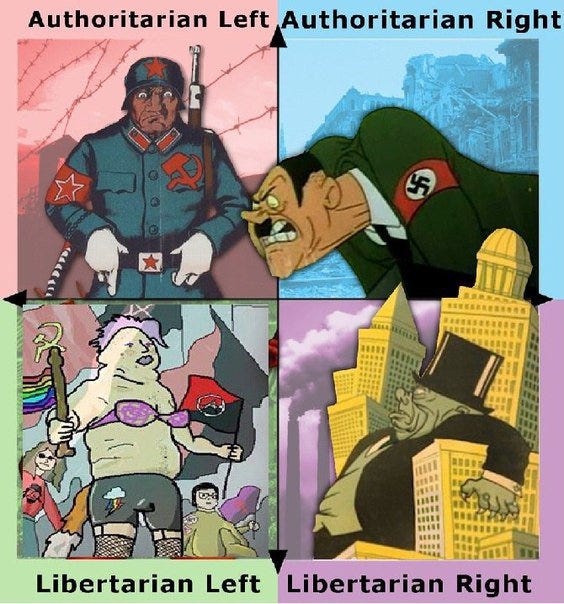

We are jumping ahead a little bit by referencing the contemporary political compass (consider it a preview), but note that according to what Eysenck above writes about L.W. Ferguson’s model, his toughminded Conservative quadrant is a lot like what we would today characterize as the authoritarian right quadrant, his tough-minded Radical quadrant is like today’s authoritarian left quadrant, his tender-minded Radical quadrant is like our left-wing libertarian quadrant and that his tender-minded Conservative quadrant is like our right-wing libertarian quadrant (see below).

However, a libertarian would want more personal freedom and less law. We read above that the tender-minded Conservative quadrant is associated with attitudes favorable of law and censorship. Libertarians want little to no law and censorship. Authoritarians want law and order and censorship. Thus, our comparison is flawed. Perhaps it is fair to say that right wing libertarians would adhere more to tradition than to law. In honor-based societies, tradition would do what law does in legalistic societies. Therefore, if we were to replace law and censorship with tradition, than our comparison is far more fitting. We will return the contemporary political compass below. Eysenck continues,

Ferguson, however, does not use these factors or axes as they stand; he rotates them through 45 degrees, as indicated in Figure 27 and emerges with two factors which he calls Humanitarianism and Religionism. These terms describe with sufficient accuracy the nature of the two dimensions or continua which he believes to underlie the structure of social attitudes, and, as we pointed out before, it is impossible to decide between his choice and ours on the basis of the intercorrelations themselves. Both solutions are equally justifiable statistically and both describe the facts with equal accuracy.

What we write and quote here is, or course, no substitute for the book itself. It’s free. No excuses. Read The Psychology of Politics by Hans Eysenck (1954).

The Bryson and McDill Model

In “The Political Spectrum: A Bi-Dimensional Approach”, published in the Rampart Journal of Individualist Thought, Vol. IV', No. 2, Summer, 1968, authors Maurice C. Bryson and William R. McDill write,

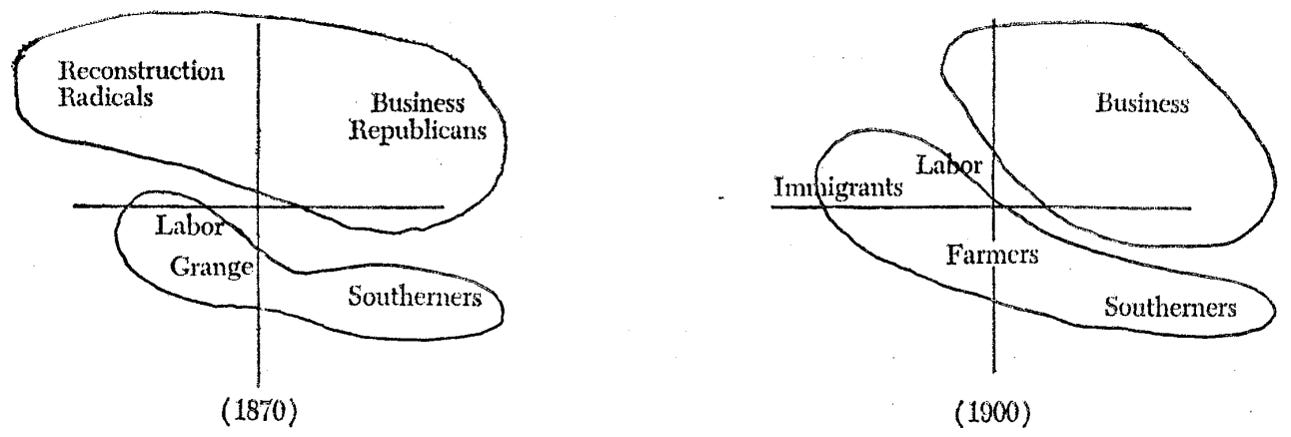

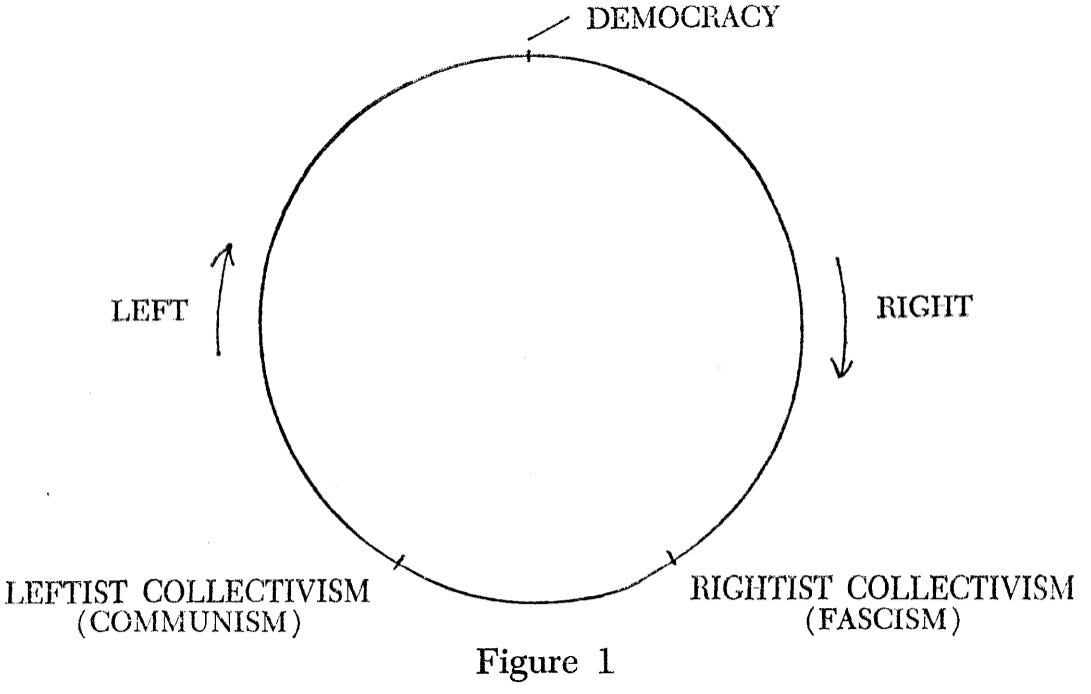

Laurence McGann in "The Political Spectrum" (Rampart Journal, Winter, 1967) raises some cogent arguments concerning the form of a proper model for the political spectrum. Briefly, the following points may be noted. First, a simple linear picture of a left-to-right alignment, with communism at the far left and fascism or nazism at the far right, is unsatisfactory in that it neglects the essential similarity between these two extremes, viz., their common totalitarianism. This similarity gives rise to a circular model in which communism and nazism occupy adjacent locations, with "democracy" at an intermediate location on the other side of the circle. Mr. McGann quite properly criticizes the circular model for ignoring the possibility of political structures that are more free, or less totalitarian, than existing democratic ones.

We regret that we were unable to find a copy of this issue of the Rampart Journal or Laurence McGann’s "The Political Spectrum". Bryson and McDill continue,

He then proposes an alternative linear model in which the linear position represents not "Ieft-" or "right-ness," but rather degree of government control, with degree of individual safety as a concomitant variable.

Another criticism, more severe from an analytical viewpoint, could have been leveled against the linear and circular models. This consists of a failure to recognize important distinctions between alternative philosophies which tend to be lumped together or at least closely associated in any linear model. Specifically, the term rightwing is commonly used to denote not only fascism, but also such concepts as the objectivist philosophy of Ayn Rand or the laissez-faire economics of Milton Friedman. And yet, even the most biased of analysts must recognize profound differences between these latter philosophies and fascism; since, in fact, these differences would appear to place the conflicting viewpoints practically at opposite poles:, it is obvious that no small modifications in the form of the political spectrum can account for the differences. Moreover, substantially similar criticisms could be leveled against the linear model proposed by Mr. McGann. In classifying ideologies only according to the degree of governmental control, his structure lumps together fascism and communism at one extreme-a grouping which might not appear totally unreasonable in today's political environment, but one which would have been badly misleading before the Second World War. More dangerously, it lumps together at the other extreme those whose philosophy is dominated by an opposition to governmental control, whether they be Goldwater Republicans or "hippies" opposing narcotics regulations. Once again, the differences between the groups are too important to be glossed over.

Many of these problems may be resolved by recognizing that we are in fact confusing two political issues that are quite distinct: the degree of government control that is exercised, and the direction in which that control is applied. Control, regardless of its magnitude, may be used to promote egalitarianism within society (the classical "left-wing" goal), or may be used to promote stability within society and hence allow the more qualified to maintain social advantage. To be sure, at the extreme points some of .these distinctions may be moot points: in a state of total anarchy, there is no governmental control and hence the question of how control is being applied becomes indeterminate; and if governmental control is absolute, then all citizens are subordinate to the state and the question of egalitarianism vs. privilege becomes meaningless. But these are pathological cases of little interest in a functioning society. At all intermediate points, the difference between the two issues is of great importance.

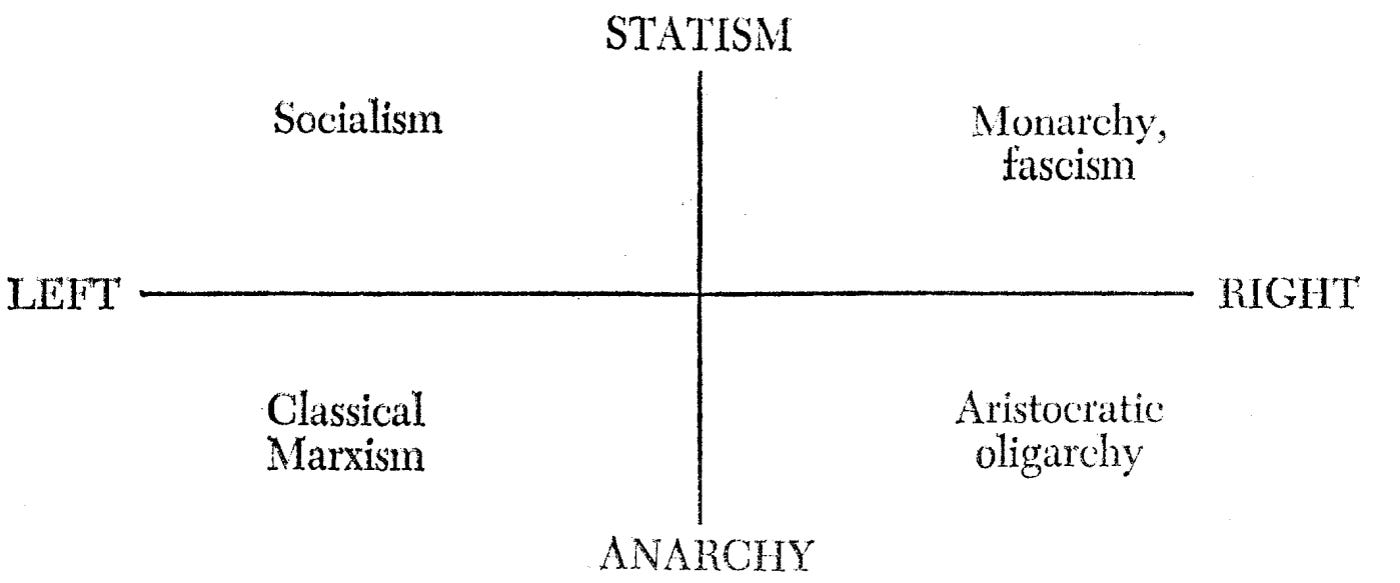

We therefore arrive at a bi-dimensional model of the political spectrum. Position on the vertical axis represents the degree of governmental control advocated (statism vs. anarchy), and position on the horizontal axis represents the degree of egalitarianism favored (left V8. right). To clarify the picture, labels in the four quadrants identify some of the traditional philosophies of governmental structures that might be located there:

The center, or origin of the coordinate system, is clearly arbitrary; it is intended to represent in a general sort of way the political center of gravity of the population being considered. As such, its location can of course vary according to the temper of the times.

The concept of political dimensionality is not completely new (for some interesting comments, see for example H. J. Eysenck's Sense and Nonsense in Psychology [Pelican Books, 1957, ch. 7).

In Eysenck’s Sense and Nonsense in Psychology the model of political dimensionality he uses is the same model he uses in 1954 book The Psychology of Politics, the model we looked at above. In fact, he uses the very same illustrations we saw above as Figure 16 A, Figure 16 B and Figure 16 C. Let’s refresh our memory, however.

Bryson and McDill continue,

However, its ramifications have evidently yet to be explored in depth. Most important for our current purposes, it explains some of the paradoxes that were noted in connection with linear or circular models.

Consider for purposes of idealization an observer whose own philosophy locates him precisely at the center of gravity, or origin 0 of the system. If he considers the relative positions of a conservative Republican at position R and a liberal Democrat at position D, they will appear to him to be totally at odds in their philosophies; they might even seem to represent the two political extremes on a small or local scale. But now, suppose he views a fascist at position F and a communist at position C. In reality these two are more widely separated in their philosophies than are the local Democrat and Republican; but when our observer at 0 looks at them, they do not appear to be at all in opposite directions. On the contrary, as indicated by the arrows, they are in roughly the same direction as far as the observer is concerned. Their common totalitarianism appears, to him, to outweigh completely whatever differences in method they might have.

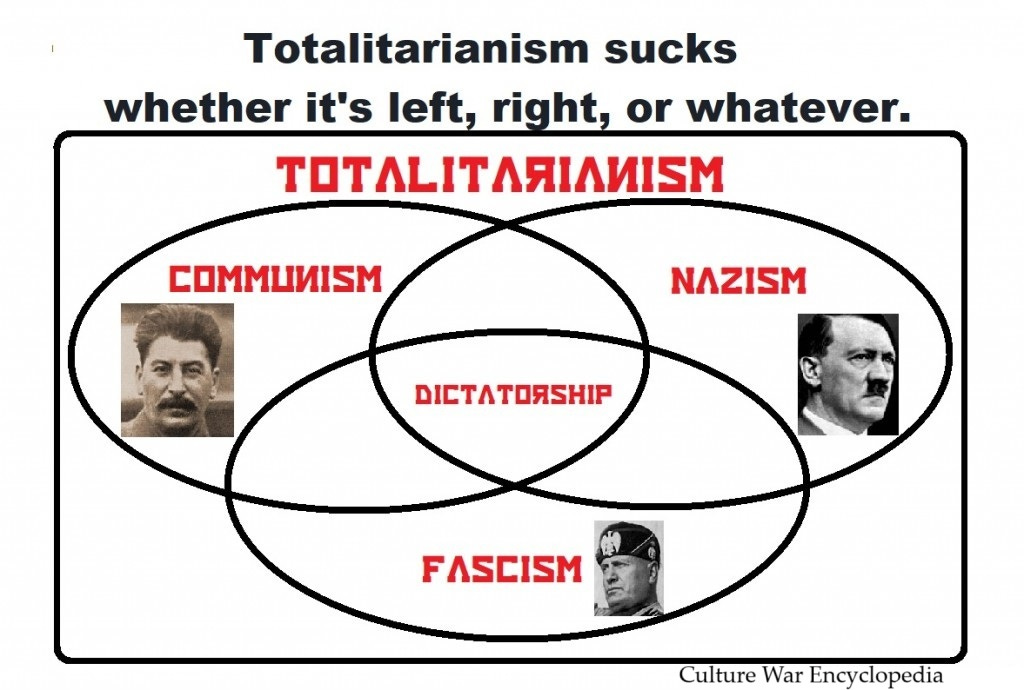

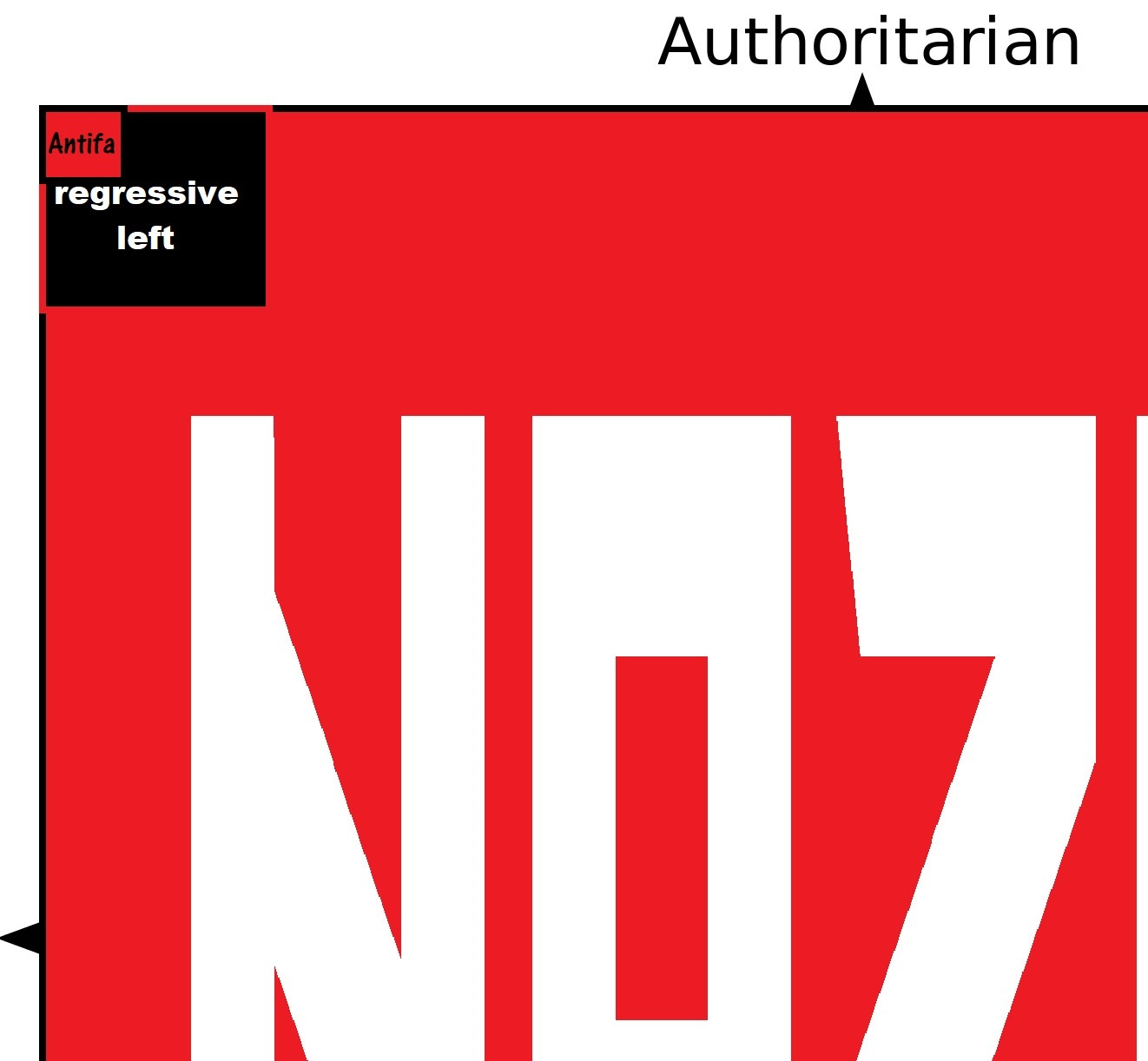

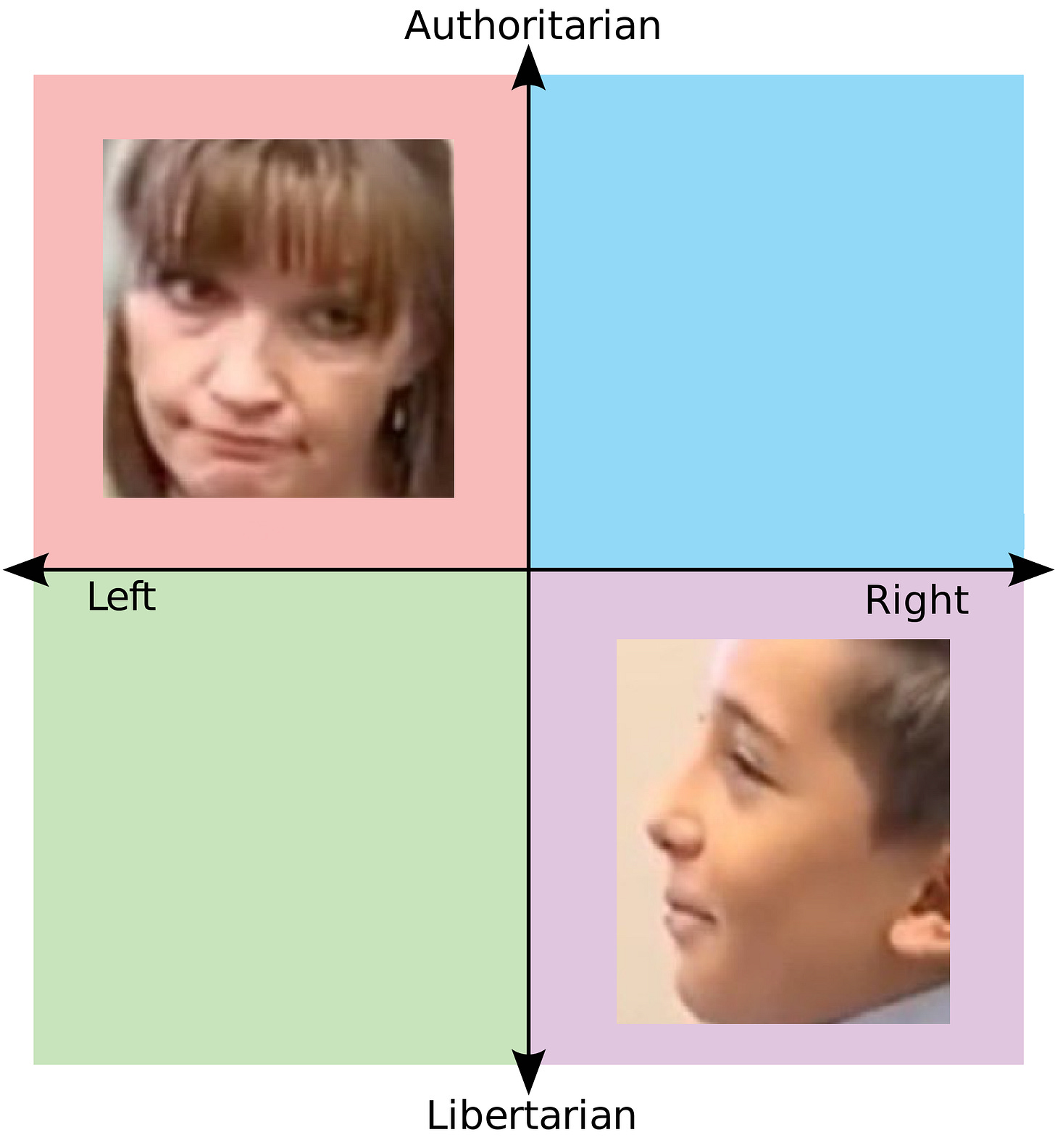

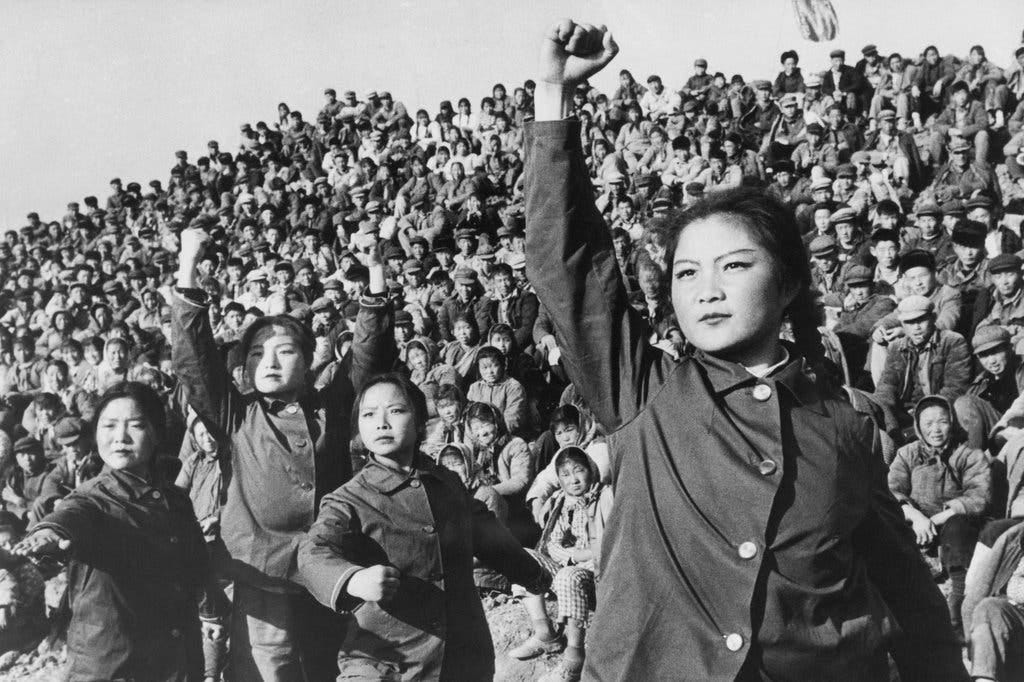

Yes, in fact, it is no trouble for we here at the Culture War Encyclopedia to note that communism and fascism (and also Nazism) are forms of totalitarianism. Stalin, Hitler and Mousseline were all dictators. Hence, we made the following. In our experience, some people do have trouble seeing it. These people tend to have the hammer and sickle in their social media bio. They see themselves as being opposite of Nazism and fascism. If I could find anyone who actually supports actual Nazism and/or fascism, I would bet that they too would claim that they are the polar opposite of a communist.

Is it not true that the terms fascist and Nazi are often used interchangeably? What about communism or socialism or Marxism or whatever term you prefer? Why is that not used interchangeably with fascism or Nazism? Is it some sort of institutional bias?

Returning to Bryson and McDill, they continue,

A person with more statist leanings, however, would be more likely to discern the differences; and an individualist who locates himself near the anarchist extreme might even say that C, F, D, R, and 0 all look like a pack of totalitarian scoundrels with no important differences at all. Thus we have the natural submersion of differences that leads to such confusions as the circular-spectrum model.

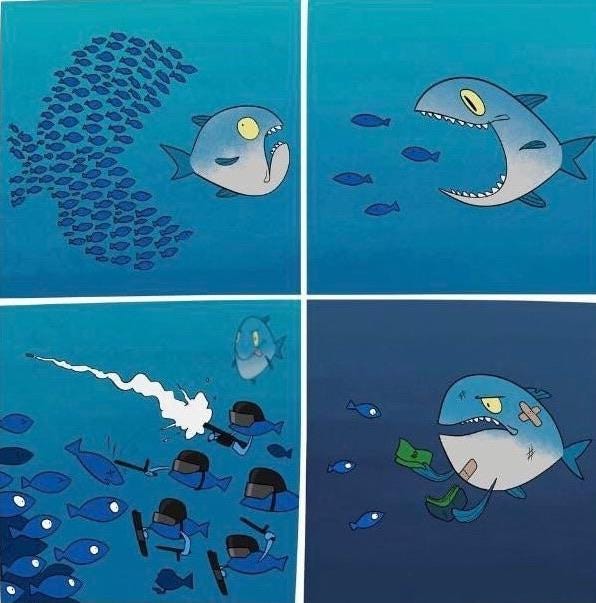

The questions of "individual safety" posed by Mr. McGann also fit nicely into the bi-dimensional framework. He argues that the individualist must be willing to accept a certain amount of governmental control in order to maximize his personal "safety-freedom"-that is, to achieve a satisfactory balance between safety from the arbitrary encroachments of his neighbors and freedom from the arbitrary whims of the state. For the individualist whose ideal society would simply permit him to develop his own talents to the utmost, the safety factor is inherent in the left-right axis. In general, the farther right the existing political climate, the more protection the individual will have from others in society. However, it should be clear that as a political structure takes on a more right-wing aspect, it must also accept a greater degree of governmental control to remain stable. An extremely competent individualist! might ideally like to see a governmental system in the far lower-right-hand corner of our coordinate plane, with virtually no government interference, but with the minimal government control being used to permit the widest possible spectrum of individual rewards. Obviously, such a system would not long endure; in the absence of governmental restraint, the disprivileged masses would sooner or later rise up to demand a degree of egalitarian reform. We may generalize to the extent of noting that the farther an individual locates himself to the right, the higher the position on the statist axis he will be forced to accept in order to realize any viable over-all position. The individual's location of his philosophy on the left-right axis corresponds to his generation of safety-freedom preference curves in Mr. McGann's terminology. Considerations of feasibility then determine how far he must go up the statist axis; this corresponds to the location of a safety freedom maximum as described by Mr. McGann.

The authors have found the hi-dimensional spectrum to he an especially useful tool in discussing and analyzing the mechanics of political activity-a somewhat more complicated process than the descriptive one of identifying an ideology. The mechanics of a political process seem to be most affected by two readily understood phenomena. First, while the most qualified, well-educated, and influential persons in society tend to be located to the right of center, the great mass of voters tends to be slightly to the left. This merely reflects the well-known Lincoln aphorism about God's apparent love for the common man; but more important for our purposes, it means that a political party or coalition cannot long remain in power if it is totally denied access to the masses of left-of-center voters. The second phenomenon, equally understandable, is that the party in power inevitably moves toward a more statist position. That is, it seems much more likely that one will attempt to justify the application of political power if one has the power. Once the power is applied, of course, there tends to be a coalescing of opposition in the opposite quadrant. How well and how fast the opposition may extend its influence seems to depend on many facets of the then-existing political environment.

Hence, the political process as pictured on the coordinate graph takes on the appearance of a stylized little clockwise minuet. The party-in-power moves toward a statist posture. The opposition appears somewhere in the anarchist half-plane. Required by the exigencies of running the government, the "ins" begin to draw on the well-qualified citizens of the upper-right-hand quadrant, thus drifting toward the right. As soon as the "outs" recognize the opportunity and can cast off the necessary ideological encumbrances, they can effect a coalition with disaffected citizens in the lower-left-hand quadrant; the "ins" are always vulnerable to attack at the right flank. (The simile is structural, not political; the right flank, in political terminology, is really the left wing.) Finally, since most of the voters are left of center, the "outs" have the opportunity of getting a majority, whereupon they become "ins" and the process begins again.

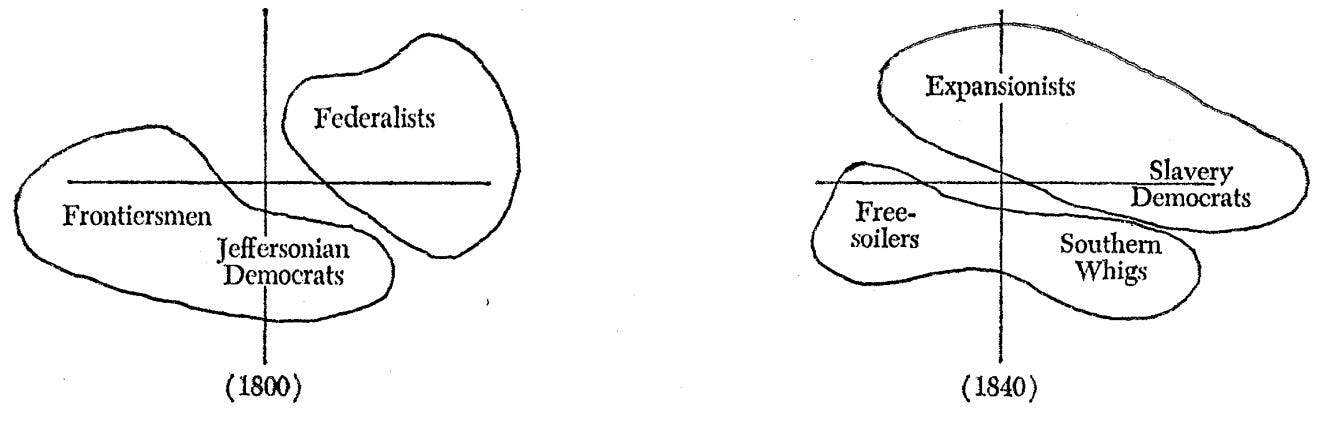

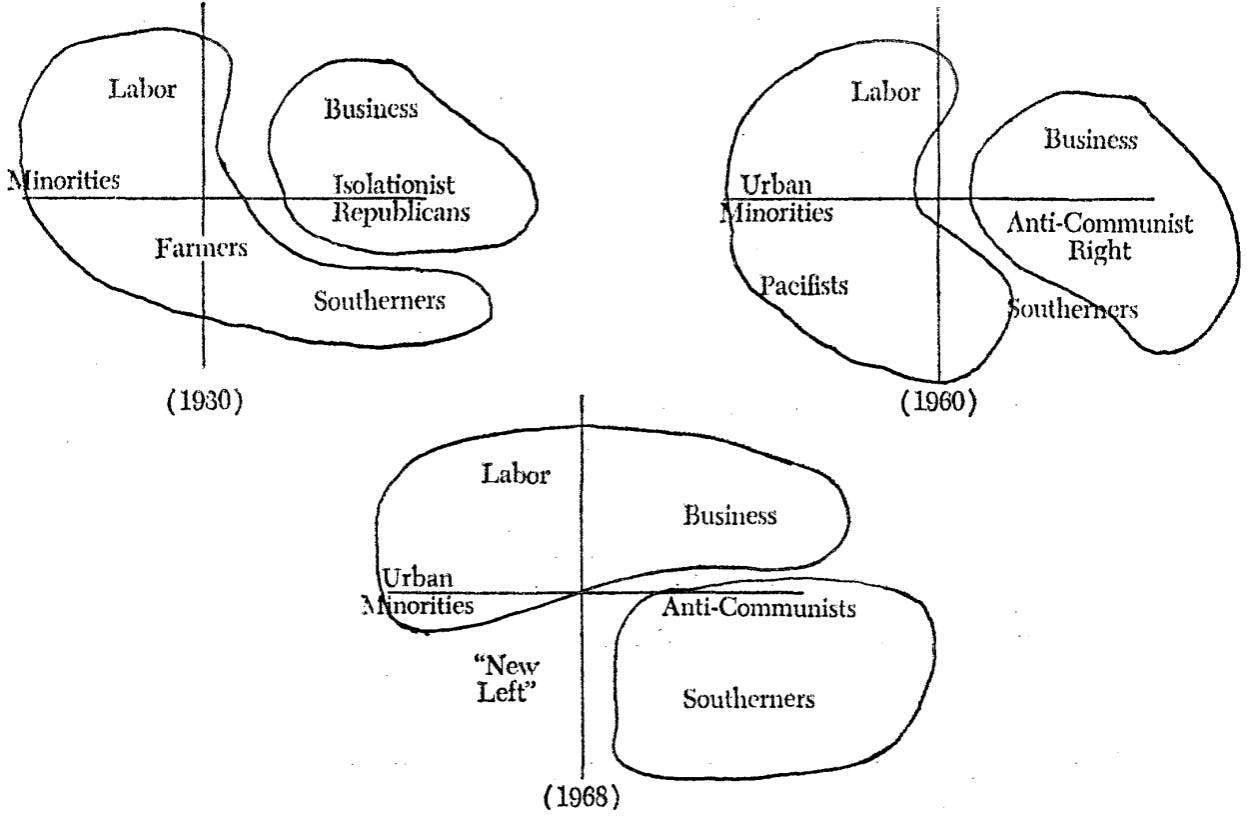

This process may be seen in the accompanying series of diagrams, giving a simplified picture of how a history of American political developments appears graphically. First, after the initial Federalist

governments before 1800, the Jeffersonian Democrats allied themselves with the frontiersmen in the new Western states to form the first real political party. From this coalition came the Jacksonian Democratic party and its left-wing-based opposition to the National Bank in the 1830's. Growth of the government's power led to the Whig reaction against ':'King Andrew" after 1830.

To the extent that the Whigs were able to ally themselves with free-soilers in the West, they were able to realize political success in the 1840's. But the alliance was too tenuous to withstand such an emotional issue as slavery, and the party eventually fell apart resulting in the growth of the new Republican party, based in the politically prosperous domain of the old free-soilers.

Under the impact of the Civil War, the Republican party was not long in becoming statist. By 1870, it was a powerful but politically vulnerable alliance of "bloody-shirt" reconstructionists and businessmen of the prosperous Northeast. To the opposition went the partially disenfranchised South and the still-weak labor and grange organizations. The Democrats ~were organizationally very weak during the closing years of the nineteenth century, but were tapping enough of the lode of left-of-center votes to be a constant threat from 1876 on.

By 1900, the Democrats had reached substantially a position of parity, although the individual popularity of its candidates and the generally high level of prosperity in the country kept the Republicans in power. But by the 1920's, the Democrats had forged an alliance of potentially mammoth proportions, including Southerners, most farmers, urban minority groups, and labor. With the obvious strength of this coalition, the magnitude of Democrat victories after 1930 is not at all surprising.

Since 1930, the Republican party has been a basically weak alliance of business and the rural right wing-isolationist at first, then anti-communist-interventionist. By 1948 and 1952, however, the vulnerable right flank of the statist coalition finally started falling apart; first the Southerners fell out, and more recently the anarchistic "new left" has evidenced the continuing disintegration. Once again, the "ins" today are vulnerable to attack within the political heartland, where the votes are.

Whether the Republicans can soon effect enough. of a coalition to get a winning combination is problematical. Only with great difficulty has a Republican-Southern bloc become a factor in presidential elections, and the current prospects of getting many votes from farther to the left. are remote indeed for the Republicans. Party of the problem is the essential truth that there are not many political entities active in the lower half-plane of the spectrum, ("organized anarchists" being somewhat of a contradiction in terms). Thus, there is little communication among the disaffected groups. Nevertheless, the opportunity for coalition is there. The Goldwaterites who oppose public welfare programs and the Berkeley radicals who oppose public police measures have much more in common than either would care to admit. Moreover, there are other signs of incipient coalitions forming, notably, the inroads among white minority groups made by the George Wallace forces. Finally, some of the liberal "ins" themselves have taken note of the threat. In his commentary following the 1968 State of the Union address, Daniel P. Moynihan made the highly cogent observation that the political strength of the future belongs to that group which can best capitalize on the groundswell of anti-government, anti-establishment opinion, both left and right, among the young.

The foregoing has concentrated on the relevance of bi-dimensionality to domestic politics. Internationally, the picture gets more complicated, but many of the same concepts are relevant. For example, the establishment of Mao Tse-tung:>s totalitarian-but-classless society in China provides a textbook example of extreme left-wing statism, vividly demonstrable in the graphical system even though far outside the domain of typical American political activity. Meanwhile in the Soviet Union, one can see the natural drift of such a left-wing statist society toward the right, in search of managerial talent.

Finally, it should be noted that while the two axes used in the discussion here appear to be the most useful ones in general, they are not exhaustive. Under some circumstances, issues which cannot be categorized as left-right or statist-anarchist, and which are in fact independent of these axes, can become important. A clerical-anticlerical axis has always been relevant to French politics, and was vitally important to the United States in 1928. Under wartime conditions, an internationalist-isolationist axis may supersede the others (although pro-war groups are sometimes identifiable uniquely as right-wing statists). A white-black "racism scale” and an active-passive "degree of radicalism scale” could also be considered, and in the future the advent of sensitive scientific questions could introduce altogether new issues. In any event, though, it seems to the authors that much is to be gained from the principle of bi-dimensionality or multi-dimensionality in political discourse-both philosophically and practically.

The L.F.E. Theory of the Political Spectrum

In “The L.F.E. Theory Of the Political Spectrum” by Bowman N. Hall, II, also published in the Rampart Journal of Individualist Thought, Vol. IV', No. 2, Summer, 1968, pages 27-31 wherein we read,

A graduate of Wabash College (A.B., 1966), Bowman N. Hall, II, is a candidate for a Ph.D. in economics at Duke University. He is presently a part-time instructor of economics at St. Andrews College in Laurinburg, North Carolina.

The thoughts expressed herein were sparked by Laurence McGann's "The Political Spectrum" which appeared in the Winter, 1967, number of this journal.

There is a footnote at this point in the text that reads,

Readers might be well advised to review this article to gain a better perspective on the L.F.E. theory.

Returning to the main text,

Mr. McGann there rightly criticized the circular theory of the political spectrum (Figure 1) for it includes no political situation less collectivized than democracy. Thus it fails to meet the requirement that any such theory must include all possible forms of political condition. Anarchy, the state of no political regimentation, does not appear on the circular theory.

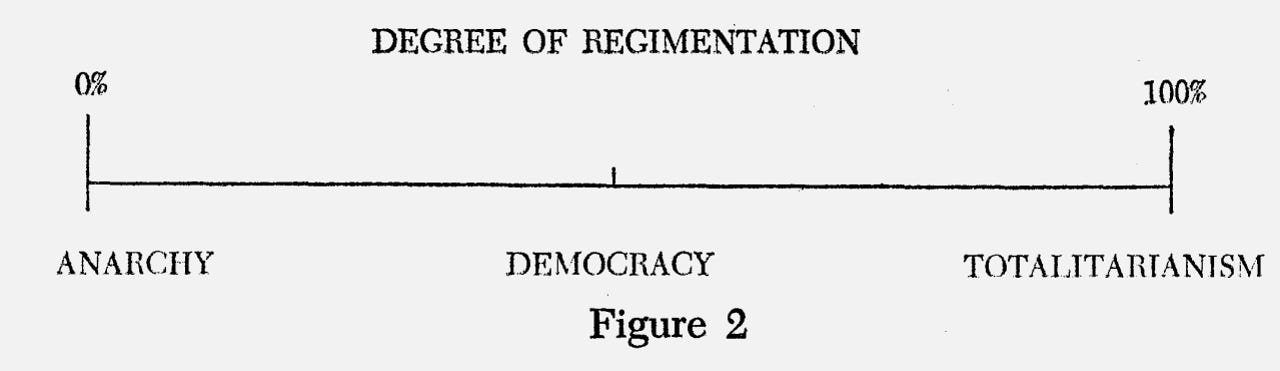

Realizing that the circular theory is unacceptable, Mr. McGann suggests the linear theory of the political spectrum (Figure 2) as a more valid alternative. The linear theory classifies possible political (or a-political) conditions by their degree of regimentation of the people by the state. Regimentation, of course, may vary from 0 to 100 per cent.

There is a footnote here that reads,

Democracy here appears to fall at about the 50 per cent level. Whether this is accurate (1 confess to having no idea) is not as important as the fact that democracy, having some regimentation, falls somewhere between the two extreme poles.

Back to the main text.

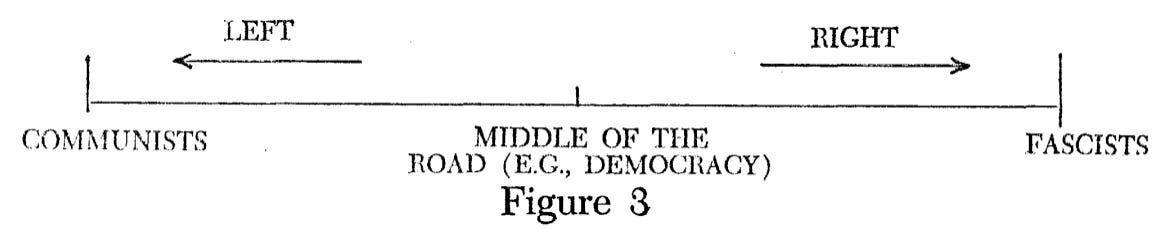

Mr. McGann, employing the linear theory, goes on to establish a graph of the “ideal" degree of state regimentation depending on one's subjective predilections for safety and freedom. The purpose of the present article is somewhat different, for it is to suggest the abandonment of the linear theory as well as the circular. Admittedly the linear theory, by its very nature, contains all political philosophies. Unfortunately, while quantity is gained by using it rather than the circular theory, some quality is lost. Clearly, the “left-right" division of political philosophies is not relevant in this construction. For example, fascists (extreme "rightists" as the term is used today) and communists ('leftists") would appear right next to each other, say at about 98 per cent and 99 per cent respectively.

There is a footnote here that reads,

I hereby propose the Hall theory of political regimentation: no matter how authoritarian, no system can be completely totalitarian for the simple reason that bureaucrats are too inefficient. Thus, 1 have left even communism with a 1 per cent "degree of freedom.”

Following the footnote, the main text reads,

So too would individualist anarchists and collectivist anarchists appear together on the left side of the diagram. However, the former anarchists are closest in philosophy to John Locke and Adam Smith, while the latter are closest to Marx and the utopian socialists. Classifying these two anarchist groups together is rather absurd for they differ in their attitudes toward private property, certainly a fundamental political distinction. Perhaps, then, a left-right linear theory might be better (Figure 3) :

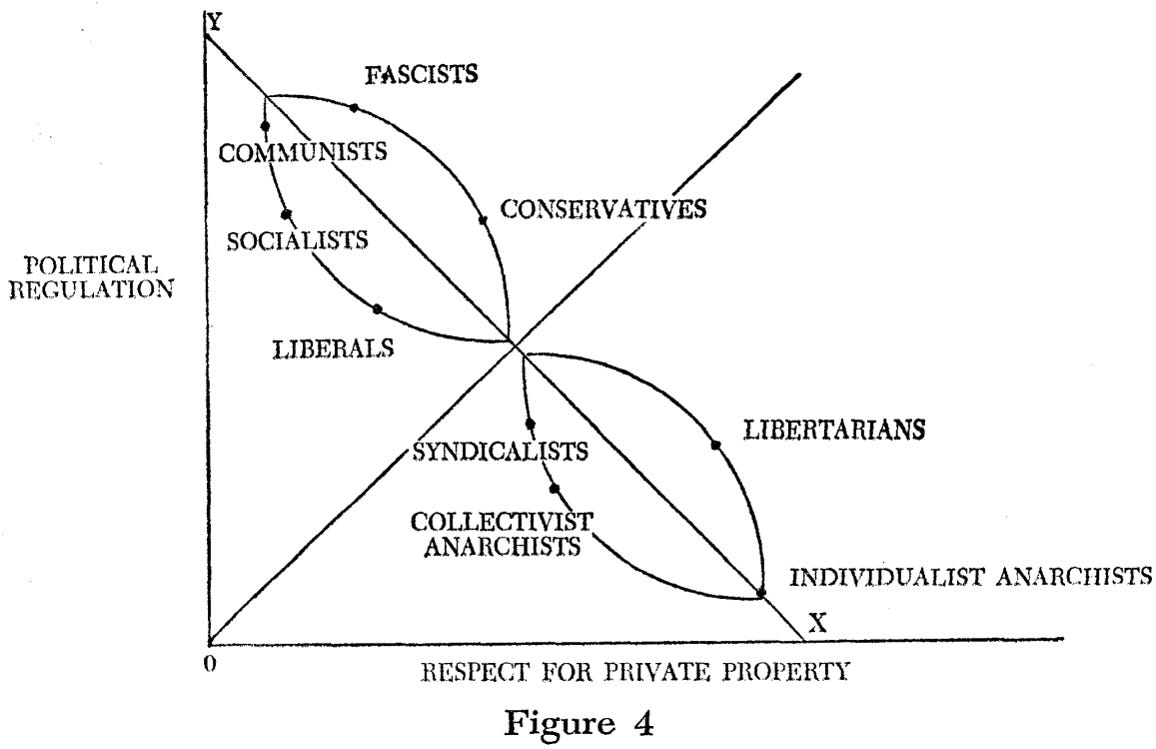

But alas, this is just the circular theory unbent; where are our anarchists? Certainly not on the right, but then neither on the left or in the center. Degrees of political regimentation have been sacrificed. It seems obligatory that we reject both linear and circular theories. Yet, if we are to have a plane geometric diagram of the political spectrum, the only choice seems to be a combination of lines and circles. At this stage, the author wishes to submit the "1opsided figure eight theory" of the political spectrum (Figure 4).

A footnote here reads

The author cautiously submits the L.F.E. theory as being original. However, he confesses to having done precious little research in the area of theories of political spectrum.

The main text continues,

This appears in the font of a graph, the Y-axis of which is "political regulation." For the collectivists, one might translate this as "well-intentioned guidance of all facets of an individual's life (e.g., cradle to grave) to ensure his happiness and security from pressures of the market place and from the pressures of choosing between political candidates-especially ones which might form an opposition to the present government." A small d democrat would take this to mean "well-intentioned guidance of most facets of my neighbor's life to guarantee that he doesn't get any more handouts from the benevolent government (which we both support financially) than I do." For the individualist, political regulation may be translated simply as "oppression of one man by another." On the X-axis, one finds "respect for private property." Many readers will question whether there can be a lack of respect for private property at the same time as there is a lack of political regulation, as does the author, but at least two political philosophies on the sample spectrum (Figure 4) seem to think this feasible.

Then a footnote,

This seems to be a totally inconsistent position but the collectivist anarchists, e.g., Bakunin, Kropotkin, Malatesta, Goldman, Berkman, etc., hold that the abolition of private property and its corollaries, capitalism and the wage-system, will lead to a communal society without government oppression. Similarly, fascists, while apparently interested in regimenting people as much as possible, pay lip service all the while to private property (restricted, of course, as may be necessary to meet the needs of the state) .

The main text goes on,

The L.F.E. theory combines the best of both circular and linear theories without their objectionable qualities. Overall political exploitation can be measured by a curve sloping downward and to the right, splitting the "eight" in half. So the higher and farther to the left a man's political condition, the more politically exploited he may expect to be. Low and far to the right indicates a position approaching pure objective freedom. “Rightists" in this context become “upper-halfists” and "leftists" are "lower-halfists."

Thus, in the main, political philosophies which are similar in fact (libertarians and individualist anarchists), similar in their conception of man and the state (conservatives and fascists), or similar in their modus operandi (fascists and communists) appear near each other on the figure. Furthermore, a line from the origin splitting the lopsided figure eight into two ovals serves quite well to separate the "'statist" from the "anti-statist" philosophies. This is useful not only for identifying various philosophies for their true nature but also to reveal what should be the distinction between left and right, e.g., statist versus anti-statist. But, as shown above, since the distinction is not in fact along these lines, the left-right linear theory must be found wanting.

Thus, the L.F.E. theory embodies the best of the linear political regimentation theory in the statist versus: anti-statist division and the best of the left-right linear and circular theories in the "upper-halfist"

versus "lower-halfist" division. What then are the limitations of L.F.E. analysis? First, a logical point must be made. To say that the United States is next to Mexico and that Canada is next to the United States is, of course, correct. But we must remember that Canada is not next to Mexico. Similarly, socialism. is next to communism, which is next . to fascism on the diagram. But socialism and fascism can only be said to be similar in that they both are located on the statist oval. Second, some inaccuracies arise from putting a given philosophy actually on the eight rather than somewhere near it. For example, the collectivist anarchists appear farther right on the "respect for private property" axis than do conservatives. By definition collectivist anarchists are thoroughly opposed to private property so their position on the eight is inaccurate, but necessary since they are anti-statists. This suggests a criticism of any theory, including L.F.E., of the political spectrum. Models are designed to be representations in miniature of some phenomenon. In constructing a model, as great realism as possible must be strived for. Nevertheless, complete realism cannot be achieved "in miniature" because this is a contradiction in terms; complete realism comes only in the phenomenon itself. Therefore, any theory of the political spectrum is subject to inaccuracies. What is herein postulated may be treated as a more realistic inaccuracy.

Also in the Rampart Journal of Individualist Thought, Vol. IV', No. 2, Summer, 1968 is “Political Spectra and The Labels of Extremism” by D. O. Miles pages 32-39;

D.O. Miles is a physicist at the Lockheed Research Laboratories in Palo Alto, California. His field is experimental liquid-state physics, and he has authored numerous scientific papers on the results of his work. He also holds patents on scientific apparatus, and some of his inventions are presently being marketed. He wrote the following article during the heat of the Goldwater Johnson campaigns in 1964, "in response to inaccurate labeling which attended that contest."

Introduction

Complex ideas or phenomena are sometimes made. easier to understand if we can construct what scientists call a "model." If the model we construct is a good one, the various parts correspond to the parts of the complex idea or phenomenon. The resulting visualization is an aid to understanding. An example is the pendulum, which has long been employed to illustrate the tendency of human beings to overcompensate when taking corrective action against some trend deemed undesirable, Although the pendulum model is not perfect in all respects, it is very useful. Nearly everyone is familiar with the manner in which a pendulum in air repeatedly swings from one extreme position to another. Further, most people can appreciate how, if the pendulum were hung in a tank of molasses as a damping fluid, the pendulum might slowly approach the equilibrium position and stop with little or no overshoot. The proposed damping fluid tending to arrest or minimize oscillations in the case of society is, of course, governmental controls. The decision whether to employ a thin damping fluid like milk, or a very viscous one like cold tar, is made by experts such as social scientists, economists, and governmental officials

The above brief discussion of the pendulum model serves to suggest how useful a model may be in stimulating thought and encouraging constructive controversy. Generations of Americans have been able to better comprehend economic and social problems by use of this model, and thus more intelligently contribute to the governmental processes. It is not intended, however, to pursue the pendulum model further. Our point is merely to state that, once a good model is constructed, our understanding of an otherwise obscure and complex phenomenon may be increased, our thoughts may be clarified, and enlightening discussion may ensue. Conversely, it must be cautioned, a poor model may not only fail to bring comprehension, but worse, give the illusion of comprehension while promoting a misconception.

The Linear Model of the Political Spectrum

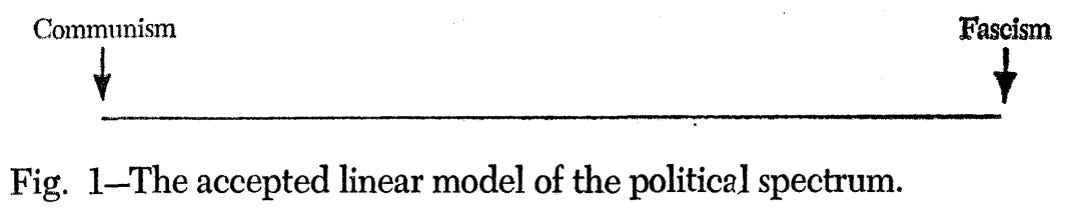

Over the last decade, another model of an important phenomenon has become popular. We shall call this the linear model of the political spectrum. This is a geometrical model. In it, the range of governmental systems is displayed by positioning them along a line, as depicted in Figure 1. At the ends of the line are placed what is regarded as the two extreme opposites of politico-governmental systems in the world-communism at the left end, fascism at the right end. Between these extremes are more moderate forms of government, with democratic and representative forms being positioned near the center.

The linear model has some serious failings. Placing communism and fascism at opposite ends of the line is artificial. From the broad, overall viewpoint of governing systems, and from the viewpoint of the individual citizen as well, communism and fascism have much more in common than they have differences. Dominant in both is the overpowering superiority of the government as compared with the individual. "Der stat ist alles, der einziger ist nichtsn (the state is everything, the individual is nothing) differs very little from communism's submission of individual goals and initiative to those of the collective or group. The individual in either system faces the same iron-fisted environment. The difference that in fascism this absolute authority in all matters rests with one dictator, whereas in communism it rests with the central committee, is trivial. The employment of mass extermination to accomplish goals set by the government is common to both systems, as witnessed by the murder of 6,000,000 Jews in 1941-1945 by the German fascist government

The footnote here is,

William Bridgwater and Seymour Kurtz (eds.), The Columbia Encyclopedia (New York: Columbia University Press, 1963), third ed., p. 1083.

Back to the main text,

and the murder of 3,000,000 Kulaks in 1932-1933 by the Russian communist government.

The footnote here is

Computed on the basis of excess deaths over normal for the Kulak fanners during the years 1932-33, by William H. Chamberlin, Russia's Iron Age (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1934), pp. 66-92.

Following the footnote,

The common end-point of extremism attained by both these systems is absolute, total authoritarianism on the part of the government, at the expense of all human rights and individual liberty.

If these systems are so similar, why are they then so antagonistic? Totalitarian governments, bent on conquest and motivated by fanatical zeal, even though they have much in common, can never trust each other, and seem always to come into conflict. The fact that fascism and communism have been at each other's throats does not in the least detract from their similarities as governmental systems.

Hence, we suggest that in any model of the political spectrum, fascism and communism be associated at the extreme of absolute governmental power, rather than separated. This immediately suggests what the opposite extreme point in our model should be. The opposite of absolute governmental power is no governmental power whatsoever. This is called anarchy. Thus, if we must employ a linear model of the political spectrum, let us think of the ends of the line as representing all-powerful government on the left; and no government at all on the right. Then, if citizens are in the middle of the line and move towards the left, they sacrifice individual rights in order to give government more power and control. If they move to the right, their government becomes weaker as more rights and responsibility devolve upon them as individuals. However, even this improvement in the linear model leaves much to be desired.

A Two-Dimensional Model

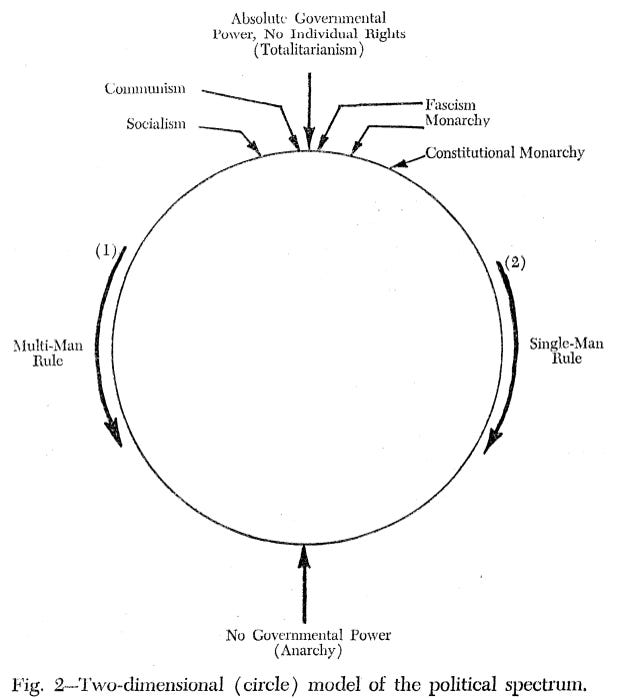

On a two-dimensional surface, let us, draw a circle as shown in Figure 2. At two diametrically opposite points we position the political opposites of anarchy (symbolically at the bottom of the circle) and absolute governmental power (symbolically at the top of the circle ).

In this model we perceive refinement sufficient to differentiate between Communism and fascism. Hence, the former is placed on the left side of the upper extreme, and the latter on the right side. What is the significance of this slight differentiation? The left half of the circle represents multi-n1an rule; the right half represents single-man rule. Thus, next to communism on the left, but further removed from totalitarianism, we place socialism with groups or committees of planners who exercise governmental control. Next to fascism on the right, we place monarchies. In general, then, as we proceed downwards around the left part of the circle in the direction of arrow (1), we encounter increasingly weaker multi-man rule systems. Arrow (2) on ,the right depicts increasingly weaker single-man rule systems. When, finally, the extreme of anarchy is reached, the arrows meet and all differences disappear due to the disappearance of governments.

The chief feature of the circle model is its graphic portrayal of the division of control between government and the individual citizen. The division existing in America today between governmental control and individual liberty could presumably be located on the circle. However, we could not decide whether to locate America's position on the right half or the left half of the circle, because ours is neither a multi-man nor a single-man rule system, but a mixture. Hence, the two-dimensional model is not geometrically complete enough to include our hybrid system.

The Three-Dimensional Model

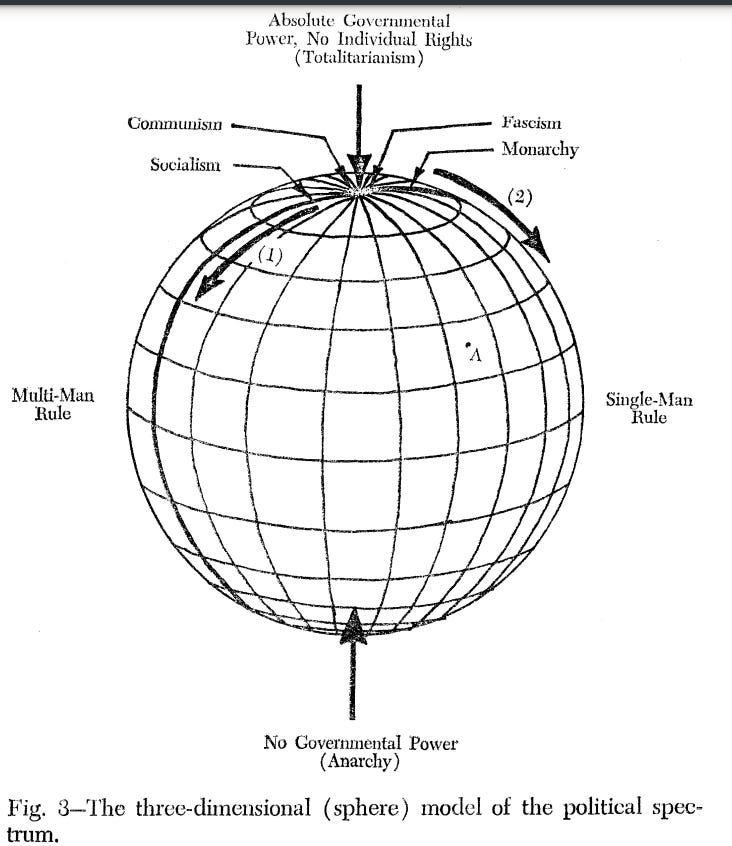

We propose yet another degree of sophistication of the model for the political spectrum, as shown in Figure 3. Here, the model has become three-dimensional and is drawn isometrically as a sphere. Like the earth, it has two poles, which may be thought of as ice caps of extremism. The south pole represents anarchy. The north pole represents totalitarianism, or the absolute control by the government of each individual's actions.

The lines parallel to the equator mark differing degrees of sharing of control between individual citizens and their government. At the equator, half of all decisions would be made by the individual and the other half made for him. At the north pole, he could not even travel to the next city to visit relatives without filling out forms to obtain government permission. (This last statement would be humorous, were it not that some of the world's people have lived under governments where this very thing was demanded!)

Next, we call attention to the great meridian line passing through both poles. Along the left half of this meridian, labeled (1) in Figure 3, are positioned all purely multi-man rule governments. Along the right half, labeled (2) in Figure 3, are all purely single-man rule

governments. By deviating from the meridian line and proceeding into areas between, as shown by point A, we achieve any desired mixture between multi- and single-man rule.

An additional feature of the three-dimensional sphere model is that its size or radius may be varied for each government considered, to signify the technological and manpower resources available to said government.

Thus, the three-dimensional model as above proposed is a three variable system, with horizontal position (angle of longitude) achieving any degree of hybridization between multi- and single-man rule, vertical position (angle of latitude) depicting any degree of sharing of control between government and the individual, and spherical radius indicating the net resources behind the government.

Unless we have overlooked some other critical variable, any governmental system may be pictured in this model. If there are other variables not included, the next degree of sophistication of any geometrical model would require a four-dimensional surface. The utility of such a model would, however, be impaired due to our lack of ability to draw the model, build it out of plexiglass, or even to visualize it in the mind's eye.

Some Practical Implications of the Three-Dimensional Model

If the superiority of the three-dimensional over the presently accepted linear model be admitted, then certain changes in our thinking must follow. However, as will be pointed out below, these changes will not in the least discourage the sacred practice of name calling!

Most prominent among the changes called for by the three-dimensional model are alterations in categorizing the conservative and ultraconservative elements in America. It has become a world-wide practice to associate the American ultraconservative philosophy with fascism. This is a downright error, if we examine the improved model carefully. Do not misunderstand. We do not propose to remove the extremist label from the American ultraconservative. We simply wish to place the correct extremist label on him. He is not, as the fascism label would suggest, at the extreme of advocating an all powerful government. Indeed, the American ultraconservative is constantly saying, "Limit the power of government." Where he belongs is somewhere close to the extreme of no governmental power-of anarchy. Hence, it is suggested that ultraliberals henceforth hurl the epithet "anarchist" rather than "fascist" at their ultraconservative opponents. There is no danger in this of calming the tempest, for anarchist is considered to be just as dirty a word as fascist. It even sounds worse! Furthermore, it falls from the tongue with a more masculinely curse-like sound: an-ar-chist!

However, lest some liberal prefer his old ways of doing things and prove too unprogressive to adopt the new terminology, let us remind him that he himself has undoubtedly many times placed his conservative opponent in the camp of anarchy without realizing it. How many times has our intransigent liberal asked his conservative opponent, when arguing about government intervention in welfare, "Then you mean to say you would do nothing?" And the conservative probably had to admit that he would, indeed, have his government do absolutely nothing.

A footnote here reads,

There is good reason why the government should not step in, as is pointed out by Henry Grady Weaver, The Mainspring of Human Progress (New York: The Foundation for Economic Education, Inc., 1953), pp. 144, 145, 202.

Back to the main text,

The implication both of the question and the reply is of weak or inactive rather than powerful government-of anarchy rather than absolutism.

Thus, let ultraconservatives henceforth be called anarchists rather than fascists. This will detract not a whit from our fun, and it at least is a shade closer to the truth.

1970 saw the publication of The Floodgates of Anarchy by Stuart Christie and Albert Meltzer which includes the following…

This comes from Section 7: Party Lines and Politics in which we read,

Political parties are associations aiming at power. Some times parties represent classes, especially when a ruling class is driven to a last-ditch defence and has to close ranks. But other factors also come into play, such as personal quarrels and ambitions, the drive of a new power elite, historical continuity, ideological differences, or a combination of some or all of these factors.

Materialistic considerations often, though not always, dominate over ideological ones, and tend to fashion the latter. The anti-clerical and free-thinking French bourgeoisie, for instance, found its way back to political Catholicism not by reason of any “light on the way to Damascus” or even by conscious decision, but solely because of general alarm at the way in which the working class had picked up its own iconoclastic beliefs. In the same way the slaves of Haiti had embraced the republican ideas of their French masters, who thereupon reacted much as would the old nobility. There has been quite some alarm here too, of recent years, in the way in which disillusion with government has spread among the younger generation.

Tories and Whigs were originally differentiated by the more progressive views of the latter section of the British aristocracy, who naturally came to expect that popular radicalism would rally behind them, even at the period when Whiggish attachment to liberty had long been consigned to the past (it was they who deported the trade union pioneers to Australia). Whigs and Tories became indistinguishable, and the party broke up. At that juncture it was the particular contribution of Disraeli to politics that he saw it was illogical that in the new, Liberal Party that inherited the Whig mantle, the urban working class should follow, not their old aristocratic “protectors”, but the very Liberal industrialists who were directly exploiting them. According to him, the natural new “protectors” of the exploited industrial workers were the reactionary landowners, who might well oppress the rural workers but had a common enemy with the factory proletariat in the manufacturing class. Given such an alliance, it seemed to him there was no reason why the Tories could not give up, their reactionary views, and become reformers at the expense of the Liberal industrialists. Universal suffrage could then favour the Conservatives-and would “dish the Whigs”. The policy was described by Carlyle as “shooting Niagara” . The sage reacted to it as did Bismarck when Lassalle tried to persuade him of this “natural alliance” too. It is in the nature of conservatism to distrust leaps in the dark, and “a leap in the dark” is exactly how Tories described their leader’s programme. Yet it was a successful leap so far as they were concerned. Disraeli associated it with popular support for imperialism. And quick victories and painless patriotism, allied to a regard for working-class votes, meant that the Conservative Party got, and retains to this day, a degree of that vote. The Liberal Party was totally deprived of the only reason for its existence. For as the capitalist prospered under empire-building, he became an integral part of the ruling class. Joseph Chamberlain took the Liberal industrialists into the Conservative camp, but it was part of a general intermarriage of the top classes. After that, the working class could either look to the Conservative and Unionist Party as its “protector”, or form its own party. Eventually that came about. The Liberal Party ceased to have relevance except as an association for personal ambitions, historical loyalties and confused ideologies. The Labour Party, however, took on the old role of liberalism, and found the working class a new type of “protector” in the civil service.

There are always reasons, false only to the revolutionary, for supporting one party against another. Victory for Tweedledum means defeat for Tweedledee. In Austria, the social-democrats and liberals supported the fascism of Dollfuss against the nazism of Hitler. Many who had sworn never to vote Labour again because it had agreed to the H-bomb that could have ended the world, supported it after the Tories brought in a Rent Act that exacerbated the housing problem. Reasons for voting are magnified out of proportion, and made into political issues. It still remains true that parties are reflections of power interests, even though it may not always immediately be possible to identify one party with one class interest.

Some people find it understandably difficult to grasp the complexity of so many parties, once they have graduated from the discovery that there are more than two or three main ones. Understanding is not made easy by the hackneyed image of the parties or ideas standing from right or left like a row of ninepins waiting for the ball to hit them. The seating arrangements of the French Chamber of Deputies, on which the terms “Right” and “Left” are based, were no doubt a convenient way of spreading the crowd around that august body, but leave much to be desired in the way of explaining what political differences are all about, so long after the French Revolution.

Just as the British public has been persuaded by the advertising world that everyone is middle-class and should live up to that standard, so the French Deputies, after the Second World War discredited the Right Wing because of its collaboration with nazism, all wanted to sit on the left, leaving empty benches on the right. Only the resumed confidence of the Right, when the bourgeoisie felt secure from social revolution (thanks to the Communist Party), saved the Fourth Republic the expense of building a differently shaped chamber.

In many countries “right” and “left” have been used in a senseless fashion, merely to indicate an attitude to Moscow. For Moscow itself, to be more “left” than they was to be suffering, in Lenin’s phrase, from “an infantile disorder”. Yet the anarchists, for instance, whatever the newspaper reader might think, are not “more extreme” than the communists; they are at quite a different extreme. Half the defeats encountered by the anarchists as an organised entity have been the result of being persuaded that they are part of a natural “left wing” progression. The Communist Party is not nearer to the Labour Party than it is to the Liberals, nor are the latter necessarily farther away from fascism than the Tories (Lloyd George, for instance).

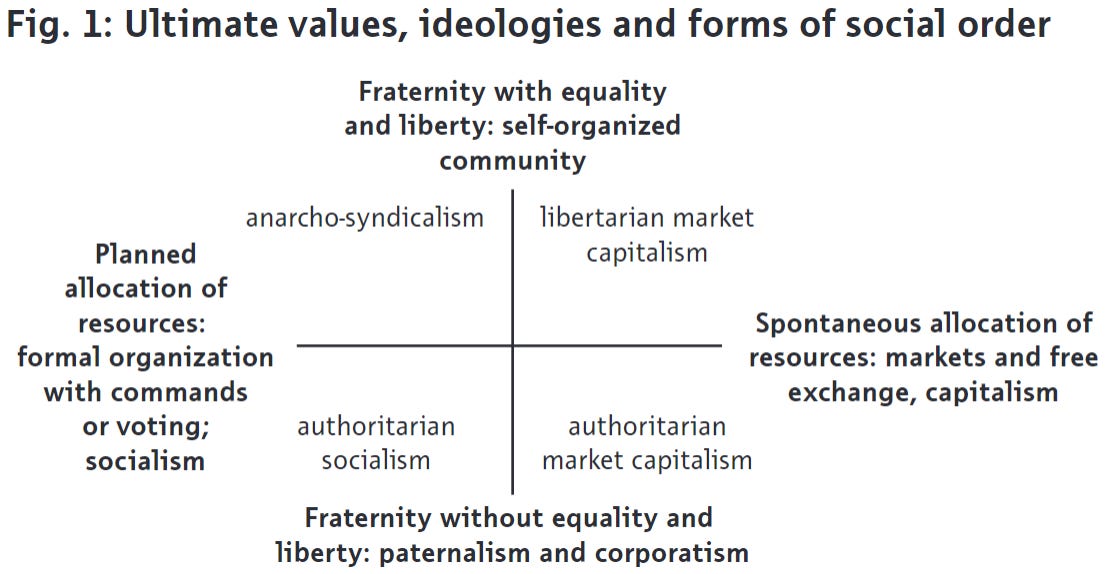

Once again we have recourse to a diagram. This supposes that there are two social considerations: individualistic and totalitarian. In the way in which we live, the basic determining factor is either the individual or the State. And there are two economic considerations: competitive and collective. The way in which we work is either capitalistic or socialistic. Ideologies relevant to the present time, not just theoretical adventures of which the inventive political mind is prolific but which fail to relate to current issues, can normally be understood in the relation of their social outlook to their economic. In this sense, the diagram is a rough-and-ready guide to political theory, and one can at least say for it that it makes far more sense than the drawing of a line from right to left, which up to now has been accepted as a suitable illustration.

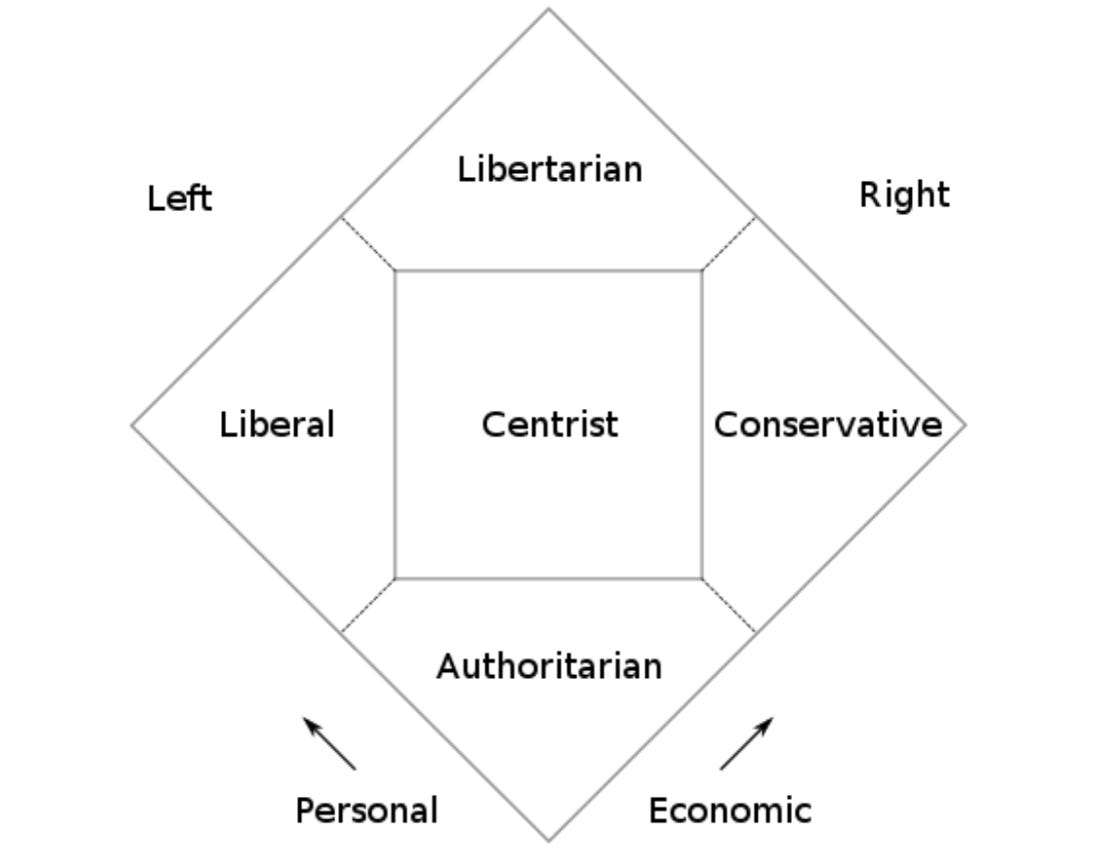

The Nolan Model

The Nolan Chart is a political model reportedly created by the late David Nolan. He was the main founder of the Libertarian Party, reportedly. Advocates for Self-Governance write,

in fact, that party was formed in his own living room in 1971.

He created it in 1969, according to DBpedia but according to Advocates for Self-Governance, he created it in 1970.

LPedia writes that Nolan

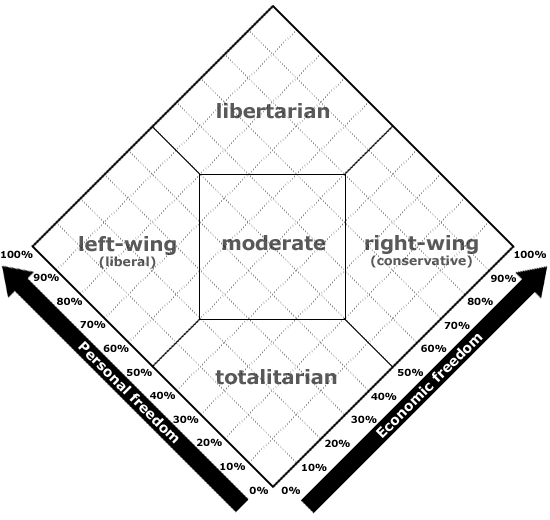

created it to illustrate the claim that libertarianism stands for both economic freedom and personal freedom (as he defined the terms), in graphic contrast to left-wing "liberalism", which, according to Nolan, advocates only personal freedom, and right-wing “conservatism”, which, according to Nolan, advocates only economic freedom.

They also state,

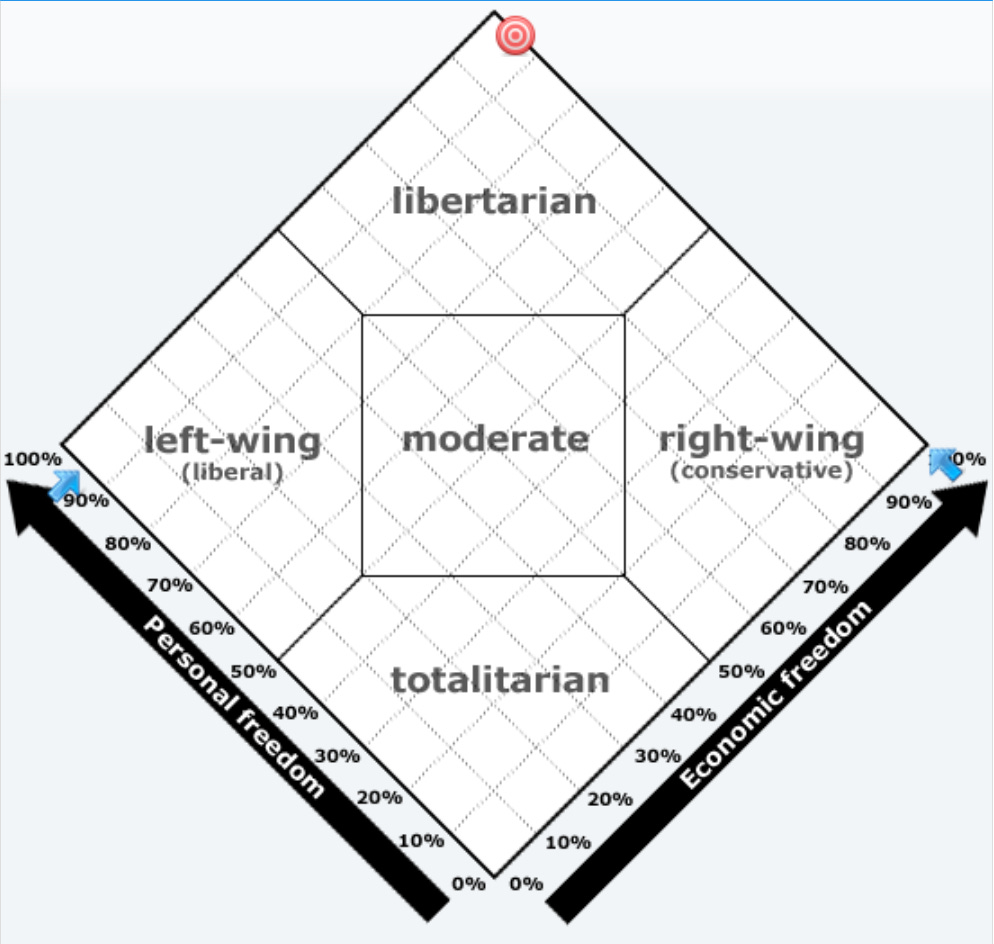

Differing from the traditional left/right distinction and other political taxonomies, the Nolan Chart in its original form has two dimensions, with a horizontal x-axis labeled "economic freedom" and a vertical y-axis labeled "personal freedom". It resembles a square divided into four quadrants, with each sample in the population assigned to one of the quadrants.

The upper left quadrant represents the political Left — favoring government that taxes more and spends more for activities such as welfare, healthcare, education, Social Security and funding for the arts and that encourages more barriers on trade and business regulations (which David Nolan labeled "low economic freedom"), but supporting personal freedoms such as abortion, homosexuality and illegality of the conscription (which he labeled "high personal freedom"). At the bottom right is its converse, the political Right, whose coordinates place it as supporting high economic freedom and low personal freedom. Those on the Right want lower taxes and fewer social programs but support regulation by the government of cultural issues and personal behavior. The Nolan Chart places David Nolan's own ideology, libertarianism, at the top right, corresponding with high freedom in both economic and social matters. The fourth quadrant at the bottom left represents the antithesis of libertarianism. David Nolan originally called this philosophy populism, but many later renditions of the chart have used the label authoritarianism or totalitarianism instead. Some critics have argued that this was an attempt to popularize the image of libertarianism as the "opposite" of ideologies with a rather negative public image, thus putting libertarianism itself in a good light. Communitarianism also exists within the fourth quadrant.

Additionally,

Many variations of the Nolan Chart have been developed, with some rotating the chart area 45 degrees in a rhomboid form to allow representation of left/liberal and right/conservative along a single axis in the manner they are typically charted. Many use different labels to describe the various types of government that would be placed in the quadrants. The original use by the Libertarian Party was represented by the Libersign and was the Party's first official logo.

You can find where you stand with regard to the Nolan Chart by taking the quiz at Advocates for Self Governance.

You can also try the political quiz at Polquiz to see where you are on the Nolan Chart.

If you take the political quiz at Polquiz and one answer every question in a way that reflects that you don’t want the government to be involved in anything at all, your position will be at the top point of the Nolan Chart.

If you make one exception in the area of immigration and choose the moderate approach (see above) your position will end up slightly to the right of the top point of the Nolan Chart (see below).

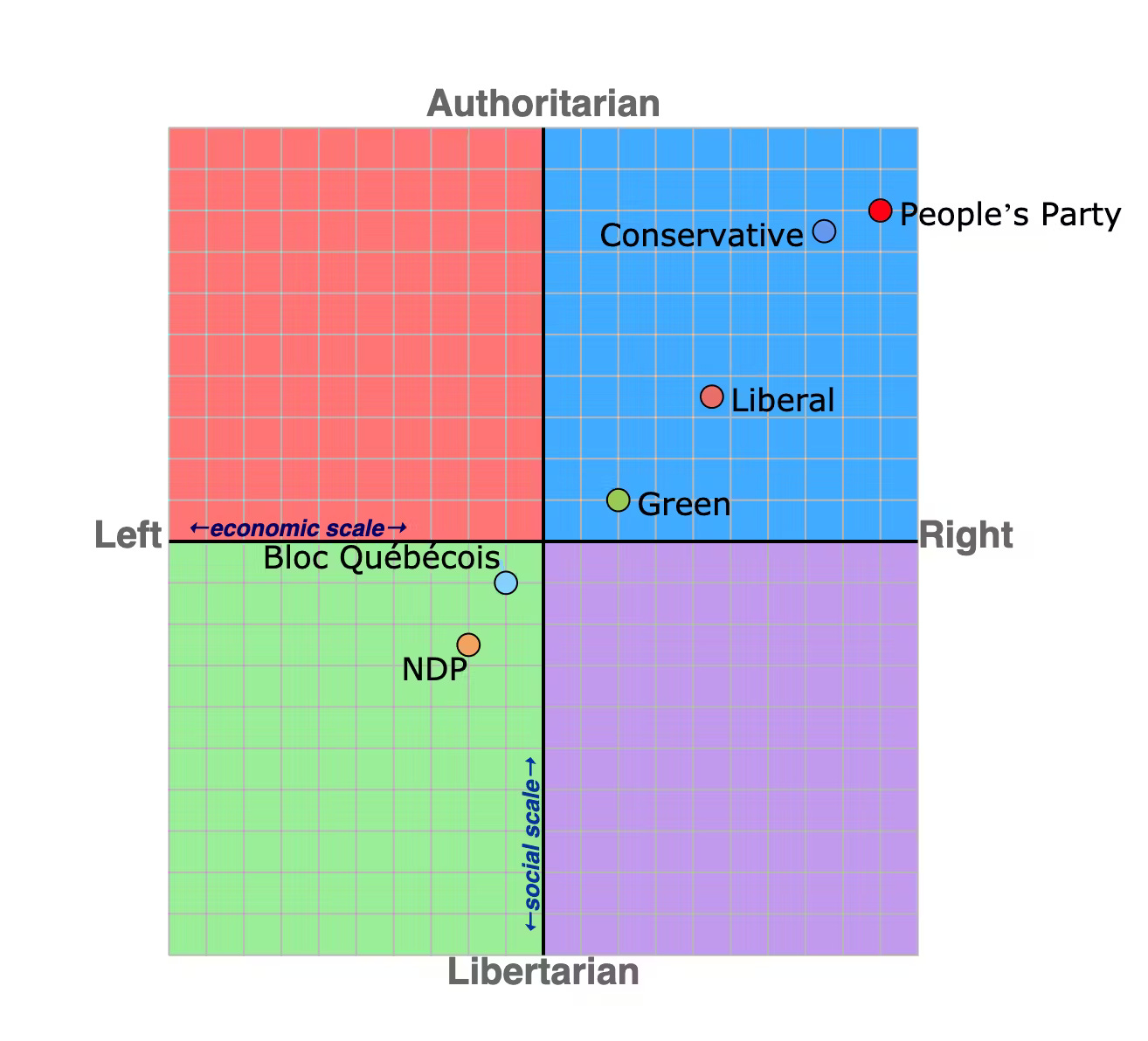

The Political Compass

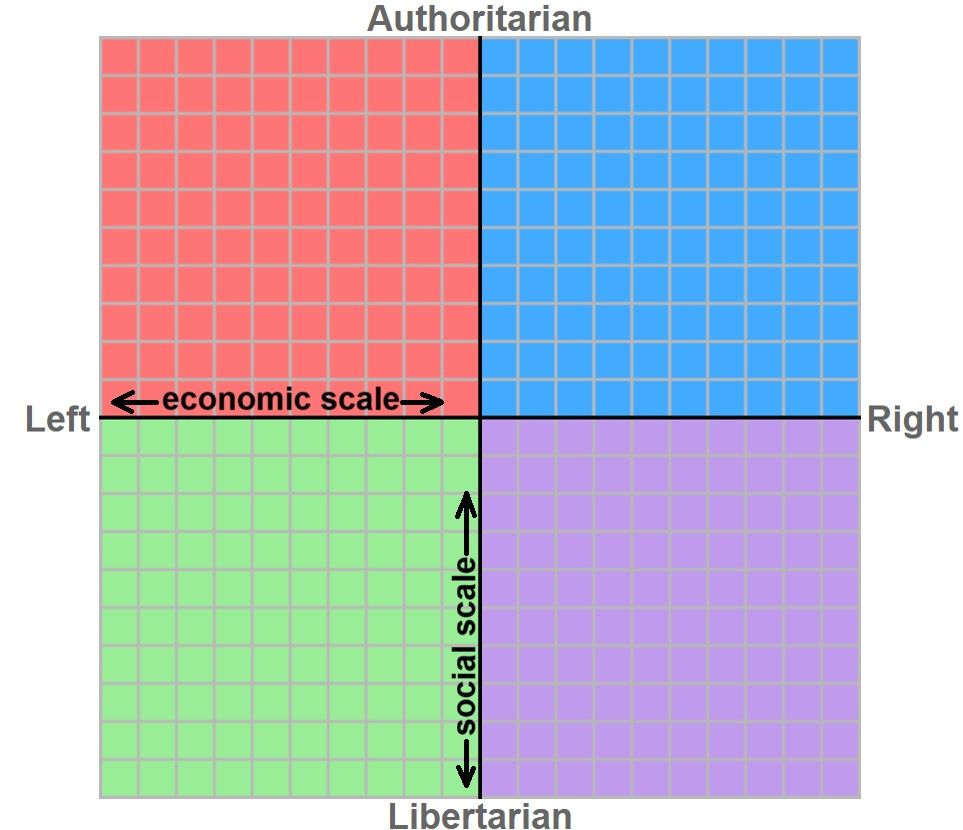

You may have taken the real Political Compass Test or some version or imitation of it and came out with a result that consisted of a point on a coordinate grid or graph as follows.

The Political Compass, has been available online since 2001, they say,

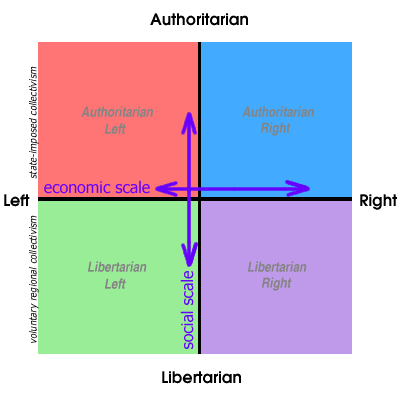

when we recognised the inadequacies of the standard political measure:

It’s certainly fine for discussing economics but to this day is still widely — and wrongly — used to describe social attitudes. France’s National Front, for example, is popularly described as “far right”, yet its economic policies have sometimes been to the left of even the French Socialist Party. The party’s real extremism is in its social attitudes. That’s why we added a social scale.

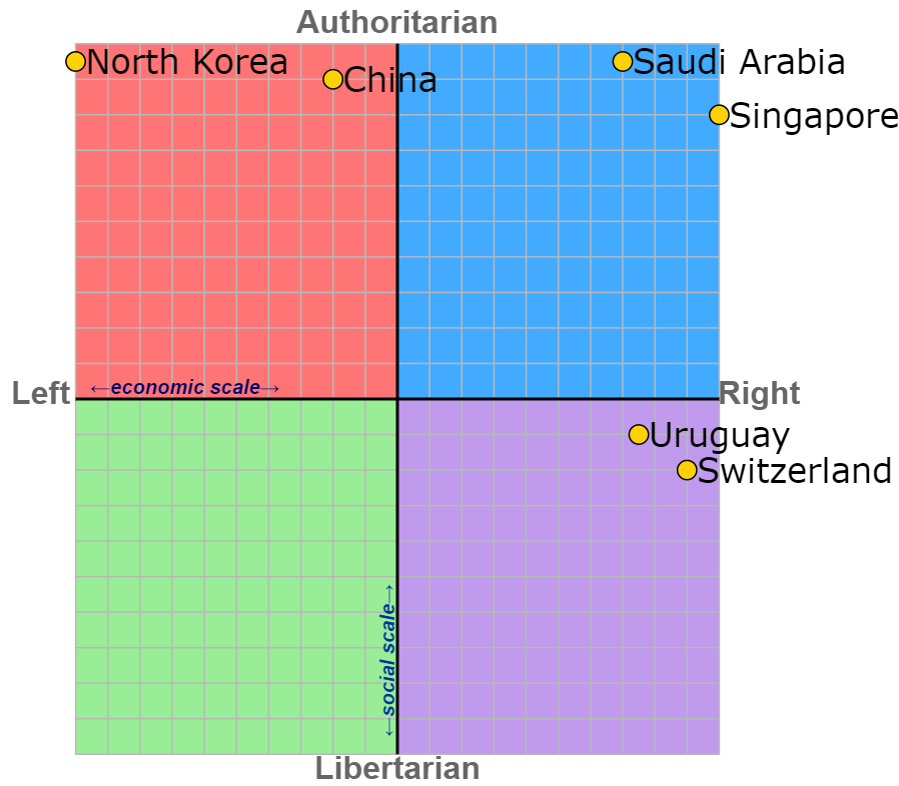

Nevertheless, the more nationalistic and authoritarian a party or individual is, the more ‘right-wing’ they’re still labelled. This, of course, is absurd. Taken to its logical conclusion, it means that the further left a country sits, the more socially liberal its attitudes are. on that basis, North Korea must be a shining model of human rights and social freedoms!

Conversely, a country may be very right wing (ie libertarian) in its economics, and be authoritarian at the same time. Singapore is a perfect example.

The Index of Economic Freedom produced by the Wall Street Journal and the conservative Heritage Foundation, hails Singapore as the economically freest nation on Earth in 2021. On the social scale, however, it’s a very different story. Human Rights Watch details its reasons for finding Singapore a deeply authoritarian state.

Take a look at a few contrasting nations on this chart:

Uruguay is currently rated the world’s 44 th most free economy, and a leading Latin American light in social freedoms — from gay and lesbian rights to legalisation of cannabis. Switzerland also has a high rating as a libertarian economy, while at the same time providing a wide range of social welfare programmes, in common with the Nordic states and a number of other western countries.

With the exception of its Hong Kong region, China maintains strong economic controls, though fewer than those associated with a more orthodox ruling ‘Communist’ party. In recent years China has shifted closer to the totally repressive social climate of North Korea, where the economy also is under the absolute control of the state. Saudi Arabia has veered futher towards a libertarian economy in recent times, but with no real relaxation of its sweeping authoritarian powers.

Accordioning to The Political Compass - 23 Years (politicalcompass.org), they have received

from New York Times, BBC, Times of India, Chicago Tribune, Guardian, Seattle Tribune and more and much positive professional feedback. They write, furthermore,

we’ve enjoyed in the national media of many countries from our earliest years — as well as from many teachers and academics who continue to use our work.

They also state,

Our essential point is that Left and Right, although far from obsolete, are essentially a measure of economics. As political establishments adopt either enthusiastically or reluctantly the prevailing economic orthodoxy — the neo-liberal strain of capitalism — the Left-Right division between mainstream parties becomes increasingly blurred. Instead, party differences tend to be more about identity issues. In the narrowing debate, our social scale is more crucial than ever.

We’re indebted to people like Wilhelm Reich, Hans Eysenck and Theodor Adorno for their ground-breaking work in this field. We believe that, in an age of diminishing ideology, The Political Compass helps a new generation in particular to get a better idea of where they stand politically — and the sort of political company they keep.

A key source of revenue has been from the copyright licenses of our images, which appear in a number of education books from publishers like Oxford University Press.

Let’s look at what an other source says about the political compass. We read in Political Compass by Decision Lab,

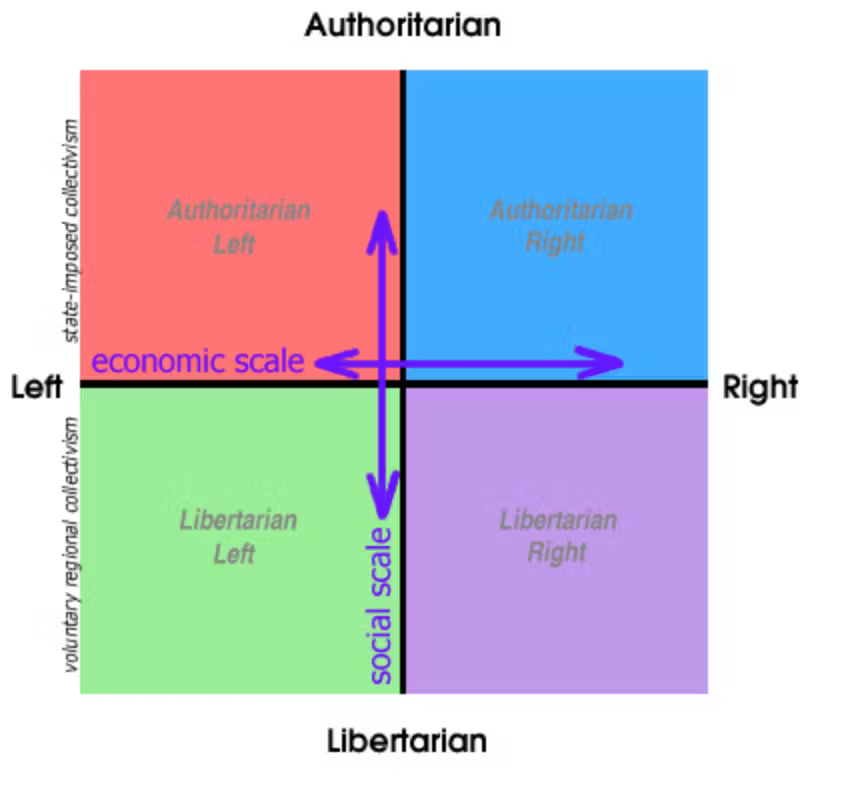

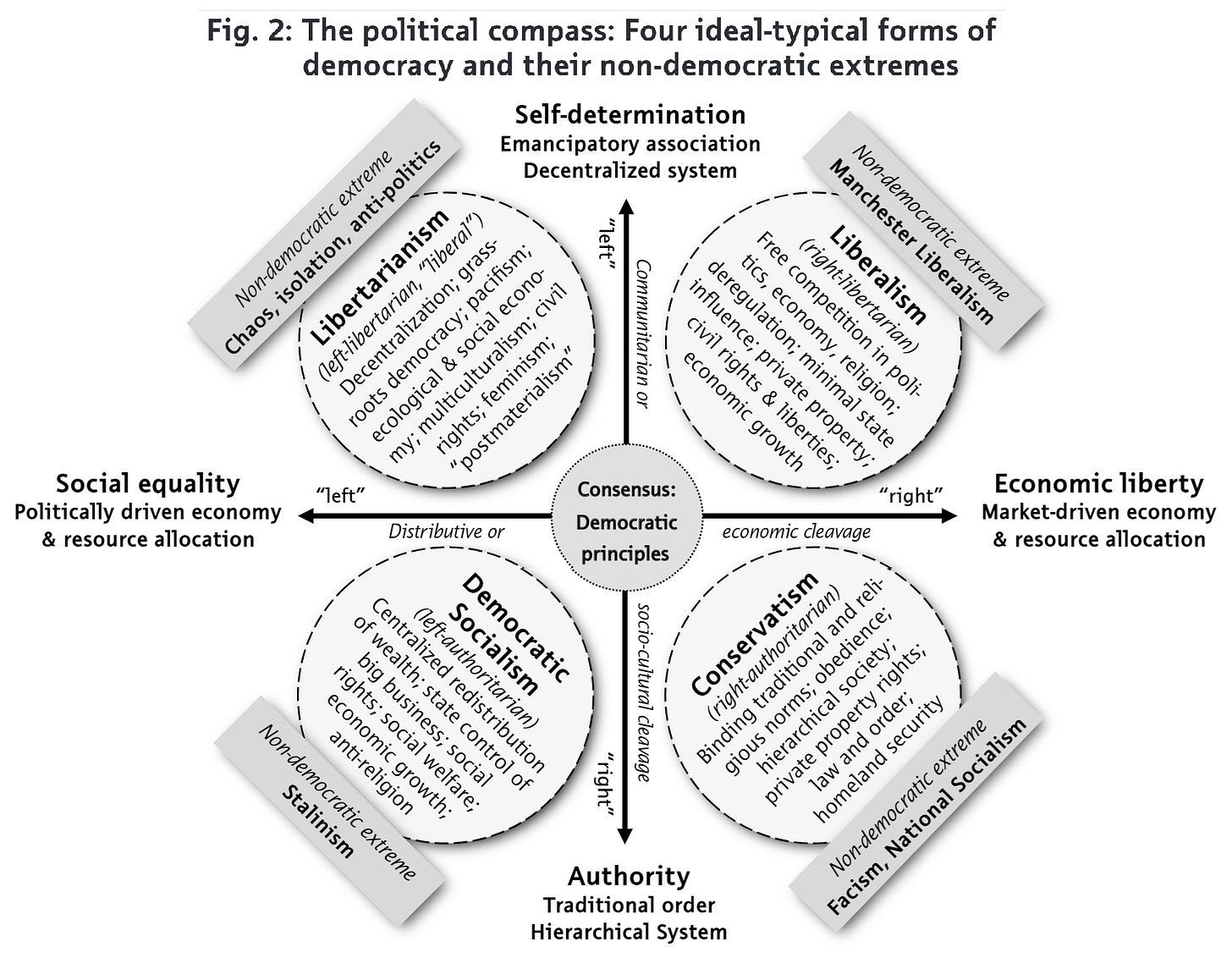

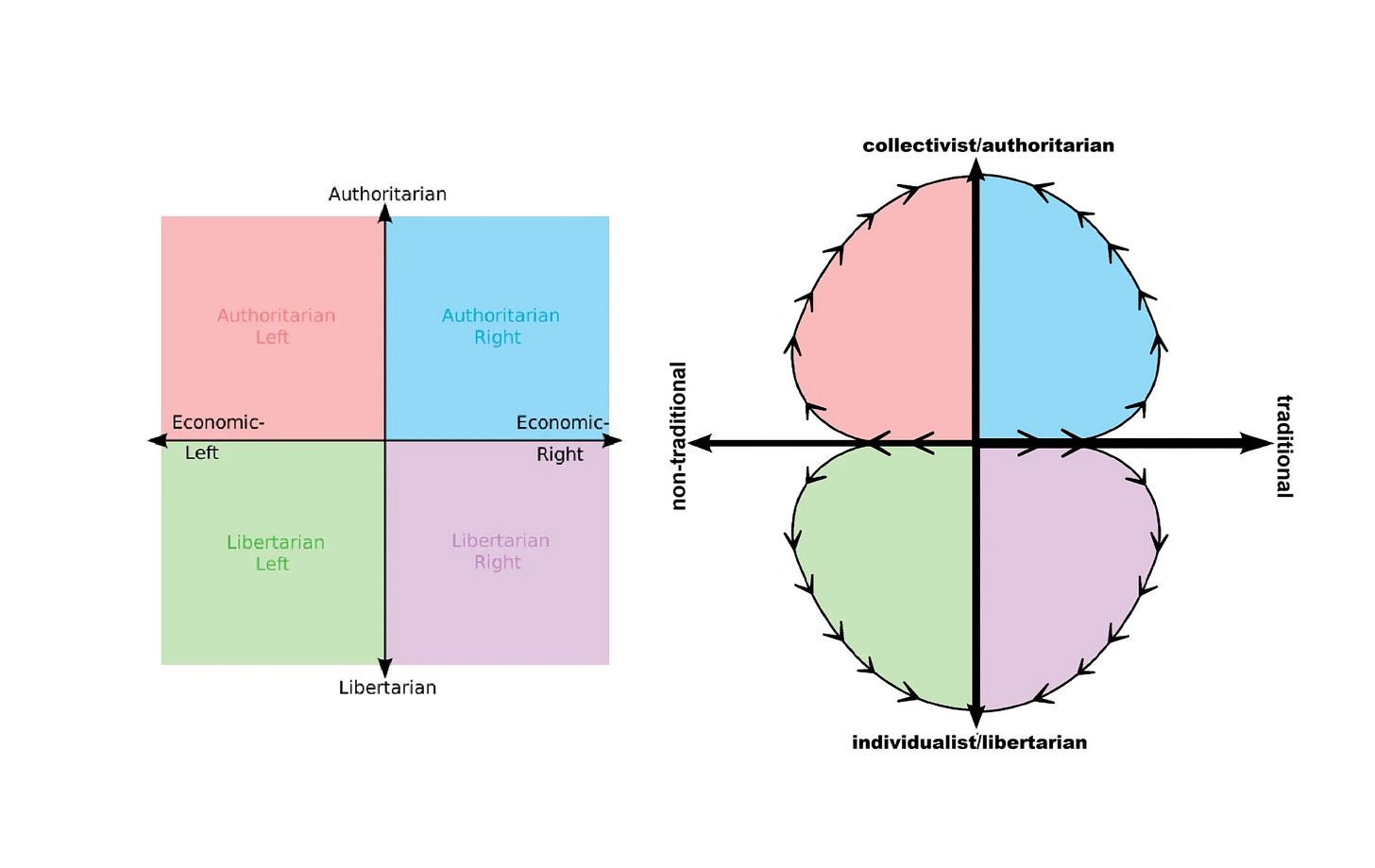

The Political Compass suggests that instead of a single-axis understanding of politics, ideologies are better measured on two separate axes: a right/left economic axis and an authoritarian/libertarian axis.

The Basic Idea

When asked about your political views, you may answer by saying that you are left-wing or right-wing. Often, these terms seem synonymous with being either liberal or being conservative; but should the concepts really be equated?

The U.S. electoral landscape is more polarized than ever, with divisions between those that identify as liberals and those that identify as conservative. One of the reasons behind political polarization may be because of an understanding of synonymity between left-wing and liberal, and right-wing and conservative. This popular single-axis understanding of politics can cause people to feel as though they have to choose a side, and then must follow the norms of that side. When politics are characterized and represented on a right/left geometrical axis, it is no wonder that the nation is more divided than ever. [Decision Lab’s footnote 1 Harman, J. C. (2018). The psychological spectrum: Political orientation and its origins in perception and culture. Undergraduate Journal of Politics and International Relations, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.22599/ujpir.25]